Procol Harum, chorus and orchestra • Copenhagen, Denmark

Saturday 15 January 2011 • Words/pictures

by Roland/Jens at BtP

‘Living,

breathing, pulsating and always inseparably intertwined’

The first

symphonic Procol Harum show I ever witnessed, at London’s Rainbow Theatre in

1972, was an altogether different affair from the 2011 Danish orchestral tour I

flew to Copenhagen on 15 January to sample. Back then much of the material had

been unfamiliar to the audience (and perhaps not altogether familiar to the

band, since it was guitarist Mick Grabham’s début); the conductor, on loan from

the Royal Shakespeare Company, had no track-record with Procol Harum, and

rehearsal time was limited. Rock/classic crossovers were still in their

infancy, and the generation gap was a live issue: the Rainbow show had begun with a short programme of light

orchestral favourites, intended presumably to assert the Royal Philharmonic’s

classical credentials before it plunged into the still scarcely-charted waters

of collaboration with the long-haired electric hooligans.

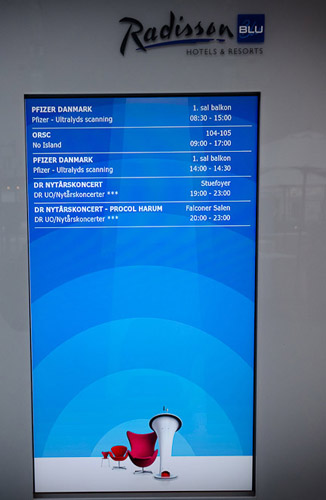

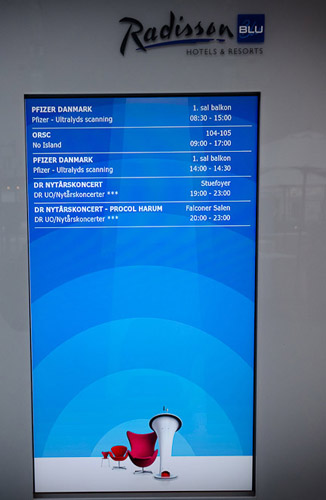

For

Procol’s Danish orchestral tour, an unbelievable 39 years and 20 orchestral

shows later, everything was much more polished (if also more predictable). These

days rockers and readers collaborate without inhibition, and indeed the average

age of the band probably exceeded that of the orchestra. Though there was no longer any barrier of

prejudice to demolish, the programme was similarly constituted. This being a New Year concert series, the intention of

the opening, non-electric numbers was evidently to put people – fresh in from the freezing,

misty streets – into a mood of happy celebration. Consequently the brief

prelude to the main attraction had been designed to imitate certain features of the BBC’s renowned

‘Last Night of the Proms’: highly varied, accessible music, with a good element

of audience participation. It soon became apparent that the sell-out crowd had

come to the

Falconer Centre in Frederiksberg – a classy city that stows away

inside Copenhagen itself – determined to enjoy itself.

For

Procol’s Danish orchestral tour, an unbelievable 39 years and 20 orchestral

shows later, everything was much more polished (if also more predictable). These

days rockers and readers collaborate without inhibition, and indeed the average

age of the band probably exceeded that of the orchestra. Though there was no longer any barrier of

prejudice to demolish, the programme was similarly constituted. This being a New Year concert series, the intention of

the opening, non-electric numbers was evidently to put people – fresh in from the freezing,

misty streets – into a mood of happy celebration. Consequently the brief

prelude to the main attraction had been designed to imitate certain features of the BBC’s renowned

‘Last Night of the Proms’: highly varied, accessible music, with a good element

of audience participation. It soon became apparent that the sell-out crowd had

come to the

Falconer Centre in Frederiksberg – a classy city that stows away

inside Copenhagen itself – determined to enjoy itself.

The show

started with strings only, the violins standing to play the Allegro from

the Concerto in G minor for Strings by Vivaldi (F.XI no 41).

Their delicacy and clarity under conductor David Firman (who characterised it

later as ‘a little “show-off” classical piece’) was immediately established, as

was the fact that – though the instruments were acoustic – we were hearing them

electrically, through the PA system, rather than

listening to their natural sound. Such a compromise is perhaps inevitable, when

a smallish orchestra – two of each woodwind (flutes/oboes/clarinets/bassoons),

three horns, two trumpets, two trombones, two percussionists, harp and full

strings (including basses): some 43 players in all – combines its acoustic

resources with the thunder of a five-piece rock-band. It was also inevitable

because there was a low wall of sound-proofing between band and orchestra, to

ensure that the acoustic players could hear themselves, which obviously divorced

the audience from the orchestral sound as well. The mix was good, however, if

not quite up to the exceptional standard heard at

Ledreborg in 2006: yet the atmosphere generated

and sustained in the darkness of an indoor show proved ample compensation.

Next it was the

choir’s turn to impress and enchant, with a transposed version (arranged by

Maestro Firman) of Bach’s well-known Air on a G string, apposite in that

it was the very piece that catalysed the composition of

A Whiter Shade of

Pale, which had in effect brought us all together in the Falconer Centre.

Swingling unaccompanied into their individual hand-held microphones, the singers

created a sublime and haunting effect, in tune with the stately simplicity of

the cyclorama backdrop to the whole ensemble: a hugely-expanded detail from the

cover of Procol’s 1973 Grand Hotel album.

Orchestral

and choral forces were then combined in a stirring blast of Bizet – the

Prelude from Carmen – with a choral addition by Firman in which the

audience was invited to sing a little – ‘Jeg elsker Carmen’ (‘I love

Carmen’) – and clap along. By way of an unpredictable, though populist,

sequel came the Vera Lynn signature Forties’ anthem

We’ll Meet Again, its

words (by Hughie Charles) flown in on a huge banner overhead. The audience

evidently knew this sentimental classic well, perhaps from its ironic use in

Dr Strangelove: yet it was performed very unironically tonight, Ross

Parker’s melody discharged with a real Light Entertainment swing. One might have

expected its sentiments to work better at the end of a show: but there’s

no denying that the crowd participation went a good way towards unifying an

audience of disparate elements: hardcore Procoholics from several continents,

with New Year neophytes yet to be won over by the Procol magic.

Lastly in

this opening foray came a version of The Sailors’ Hornpipe (‘Jack the

Lad’), played with swaggering accelerando by the orchestra, in which the

audience was invited to clap and whoop along, participating additionally on

little kazoos, or perhaps vuvuzelas, that we’d been offered in the foyer on the

way in. About 19 cm long, predominantly square in cross-section, these little

tapering plastic-and-card instruments – tuned very approximately to B4,

493 Hz – were decorated with the Danish and British national flags, the

UnderholdningsOrkestret logo and the Procol ‘lifebelt’, and the caricatured

image of Procol Harum that also adorned one of the evening’s new tee-shirt

designs, signed by ‘Cookie’

– who is not, as some had surmised, Procol’s manager Chris Cooke, but rather the

illustrator used by Weird Fish tee-shirts, a brand favoured by soundman Graham

Ewins in particular, whom Chris had encountered by chance during a motorcycling

expedition.

Lastly in

this opening foray came a version of The Sailors’ Hornpipe (‘Jack the

Lad’), played with swaggering accelerando by the orchestra, in which the

audience was invited to clap and whoop along, participating additionally on

little kazoos, or perhaps vuvuzelas, that we’d been offered in the foyer on the

way in. About 19 cm long, predominantly square in cross-section, these little

tapering plastic-and-card instruments – tuned very approximately to B4,

493 Hz – were decorated with the Danish and British national flags, the

UnderholdningsOrkestret logo and the Procol ‘lifebelt’, and the caricatured

image of Procol Harum that also adorned one of the evening’s new tee-shirt

designs, signed by ‘Cookie’

– who is not, as some had surmised, Procol’s manager Chris Cooke, but rather the

illustrator used by Weird Fish tee-shirts, a brand favoured by soundman Graham

Ewins in particular, whom Chris had encountered by chance during a motorcycling

expedition.

As conductor

David Firman was to put it later, this opening mêlée of tunes had been chosen,

by impresario Jens Hofman (‘who knows his audience well’) to ‘exemplify for the

Danes what a happy boisterous “New Year/last night of the Proms” might be.’

Perhaps this notion was foreshadowed in Procol Harum’s famous pairing of TV

Ceasar and Rule Britannia, as first heard at the Hollywood Bowl (with

the LA Philharmonic) in 1973?

Our very

genial MC was Hans-Otto Bisgaard, known to the overseas brigade only from his

role as compère at Ledreborg, but familiar to the home crowd from his many years

of championing Procol Harum on Danish Radio, as well as his activities in many

other spheres of light entertainment (see also

here).

Taking his cue from the album-cover backdrop, and the fact that the Falconer

Centre really does contain the ‘grand hotel’ in which many of us were staying,

he introduced the band with a simple but effective line: ‘Checking in right now

at the Grand Hotel, Gary Brooker and Procol Harum!’

And Procol

took to the stage. Imagine my surprise … open-mouthed amazement, in fact … as

they trouped, or trooped, on to the stage dressed in full evening tails and toppers,

chaperoned by a dedicated usher reminiscent of the bellhop from some classy

hotel of yore. This gratuitous – yet amusing – sartorial gesture was greeted

with warm laughter and cheers by the audience.

1

Grand Hotel

Grand Hotel

– also the starter at Ledreborg, the last orchestral show Procol Harum played in

this land where they are made so welcome – came straight in without

preliminaries; the instant applause for the opening notes confirmed that this

was an audience that really knew the repertoire. The opening was marked of

course by Gary Brooker’s soulful vocal, backed by the high strings, and

individual tenor notes from Geoff’s guitar. Initially this guitar, and Josh’s

Hammond XK-3c, seemed rather low in the mix; perhaps the drums needed a tad more

bite as well. Geoff Whitehorn, whom Brooker had namechecked at Ledreborg as

‘only man without a suit’, again defied the white-tie convention, sporting under

his tails a tee-shirt on which a red dicky-bow had been printed (this was

reminiscent of Mick Grabham’s get-up on the Something Magic photoshoots;

and the guitar – Geoff’s Terry Morgan 1959 Les Paul clone – compounded his

(doubtless coincidental) parallel to the original Grand Hotel guitarist).

There was a great double-length fill before ‘It’s mirrored halls …’ from Geoff

Dunn (the first to shed his tail coat).

Brooker was in

exceptional voice, very bluesy – his off-mic vocalisations are a sure sign that

he’s enjoying himself – and the choir answered his French-accented hook with

evident delight. ‘I know for certain that the choir have a ball – they love

singing the material,’ as David Firman wrote to me mid-tour (by the end of the

tour, they were treating audiences to the occasional Mexican wave!). ‘The orchestra also

enjoy the richness and subtlety of the music, and the quality of the orchestral

writing.’ Gary’s piano was deft and nimble, perhaps reflecting the unusually

extensive rehearsal period with the orchestra; but the lead violin on this

occasion was arguably not as flexible in his vibrato as his counterpart had been

at Ledreborg in 2006. The arrangement featured fabulously lush orchestral and

choral effects in the second part of the ’22 mandolins’ section: surely this is

as far from rock music – even from the Slavic

Ochi Chyornije melody that

some say inspired it – as an electric band can get! When Geoff’s solo finally

broke through, he reliably covered the Grabham melodic line, adding

ornamentation of his own. In verse three the brass players took to the

stratosphere, with great control. And Gary Brooker for once stuck with the

standard, non-localised lyric, so it was not ‘Frederiksberg girls’ who always

like to fight. As he sang the very last phrase of the slow playout, the choir’s

voices hung like a vapour trail in the air high above him.

Brooker was in

exceptional voice, very bluesy – his off-mic vocalisations are a sure sign that

he’s enjoying himself – and the choir answered his French-accented hook with

evident delight. ‘I know for certain that the choir have a ball – they love

singing the material,’ as David Firman wrote to me mid-tour (by the end of the

tour, they were treating audiences to the occasional Mexican wave!). ‘The orchestra also

enjoy the richness and subtlety of the music, and the quality of the orchestral

writing.’ Gary’s piano was deft and nimble, perhaps reflecting the unusually

extensive rehearsal period with the orchestra; but the lead violin on this

occasion was arguably not as flexible in his vibrato as his counterpart had been

at Ledreborg in 2006. The arrangement featured fabulously lush orchestral and

choral effects in the second part of the ’22 mandolins’ section: surely this is

as far from rock music – even from the Slavic

Ochi Chyornije melody that

some say inspired it – as an electric band can get! When Geoff’s solo finally

broke through, he reliably covered the Grabham melodic line, adding

ornamentation of his own. In verse three the brass players took to the

stratosphere, with great control. And Gary Brooker for once stuck with the

standard, non-localised lyric, so it was not ‘Frederiksberg girls’ who always

like to fight. As he sang the very last phrase of the slow playout, the choir’s

voices hung like a vapour trail in the air high above him.

‘Thank you

very much and good evening,’ said The Commander from his piano. ‘How’s everybody

feel tonight? Saturday night? Like to do some old ones and some different ones

tonight: and from our second album, Shine on Brightly.’

2

Shine on

Brightly

This quintessential 60s' Procol song

burst in massively and with only a drumstick count-in (a while back, it used to

be heralded with the Piggy Pig Pig rhythm from the piano’s left hand).

Bravura fills from Geoff ‘Baby-Face’ Dunn, his kick drum very prominent, were

reinforced by the orchestral percussion, and the Hammond sound was now

altogether more massive. I noted that this was a full, broad earful that Phil

Spector in his heyday would have been proud of. In the second verse the high

strings played simple, sustained notes to marvellous effect, and ’celli and

violas doubled the Dave Knights bassline. Josh Phillips, having doffed his tail

coat, turned in a nice solo close to the Fisher template, with some added

ornamentation in the end part, which competed for our attention, to an extent,

with some detailed fill work from the drums. Gary’s voice cracked plaintively on

‘and though the Ferris wheel spins round’, which always struck me as the most

plaintive part of the original album recording. The rhythmical piggy-piggery was

doubled on the tuned percussion, and the choir joined in for the playout,

sometimes singing with Gary, sometimes without. Hollywood harps swelled the song

to an ending on a suspended chord that was finally resolved as the applause cut

in. This Shine on

Brightly

brightly outshone the rehearsal recording from Edmonton that was recently

released as a bonus track by Salvo Records.

During this

number the bellhop had come and removed a flight case that had been left

onstage, propped in front of the Hammond. I wondered if this reflected a desire

for visual continuity, implying that the show was being filmed to cut in with

other performances at the same venue, as at Ledreborg: but sadly conversation

with Jens Hofman, after the show, revealed that this was not the case. Jens did

say, though, that an audio selection would be broadcast at some point on

Danish

Radio, and this will surely be

a richly-anticipated event in that country. He also revealed that this

lavish event had been his dream: ‘Ledreborg was easy, I knew we could

do that: but to take the whole ensemble on tour …’. He modestly

refrained from disclosing whether he’d expected it all to sell out in

such a spectacular fashion, requiring additional shows to be scheduled

in three of the four cities concerned.

‘Thank you

very much, it’s nice to be back in the Falconer Centre. I think this is probably

the forty-third year that Procol Harum have played here in one form or another.

1967 we came here first. Most of you are not even that old, I can tell,’ said

Gary (though in fact the people around me in the twelfth row were generally

younger than the typical Procol demographic). ‘We’d like to have the assistance

of the great DR Vocal Ensemble for this one, which is called Fires (Which

Burnt Brightly).’

3

Fires (Which Burnt Brightly)

It was neat that Gary Brooker had scheduled Procol's two Brightlys back

to back.

This elegant number, the younger of the pair,

was as powerful and stately as I’ve ever heard it live: the orchestration goes

considerably beyond what was achieved, or attempted, on the 1973 album: there

was a tinkle of high percussion for ‘malice and habit’ (it could have been a

glockenspiel, though I fancy I saw a celesta in action high up at the back of

the orchestra), which also lent a certain plangency (originally conferred by

harpsichord, which was absent on this occasion) to the Bach-like repeated

right-hand motif. The bugle-calls in the second verse came through the mix with

perfect clarity: as Gary had pointed out to me at Christmas in Southend (before

the third of three gigs with his ‘other’ band,

No Stiletto Shoes), these are not

mere colouring, but are two authentic military calls that he has succeeded in

weaving into the harmonic fabric. This is a song with a long verse-structure,

benefiting from intricate and fresh chord-changes; but the two solo breaks that

separate the three vocal verses use exactly the same ‘backing’ and one wonders

if the composer ever contemplated introducing any contrasting material, or some

change of metre, for variety’s sake.

As it was

the first solo, over Geoff’s crunchy comping, came from Josh, who made neat use

as always of the Leslie, treating us to an unexpected glissando in the middle

and at the end. (Whereas at Ledreborg no Leslie was visible – it was stowed

under the stage – here Josh’s Leslie was apparent on stage beside him: it was a

surprise, after the show, when he vouchedsafe that the cabinet was there for his

own monitoring purposes only, and that the organ chorale effects heard via the

PA originated on board his digital Hammond!). Nice drumming from Mr Dunn gave us

fills in occasionally unpredictable places, cutting across the established

metre.

In

verse three the texture lightened, and long held chords from the choir were very

effective in highlighting the resignation and despair in Keith Reid’s words. The

anvil motif, which sounded at ‘cast sailed away’, added a Wagnerian weight; in

characteristic Procol fashion, low guitar notes reinforced the stepwise bass

line.

In

verse three the texture lightened, and long held chords from the choir were very

effective in highlighting the resignation and despair in Keith Reid’s words. The

anvil motif, which sounded at ‘cast sailed away’, added a Wagnerian weight; in

characteristic Procol fashion, low guitar notes reinforced the stepwise bass

line.

The second

instrumental verse was heralded by a great swell of choral chording, and taken

by Gary Brooker at the piano. It’s surprising to fans that the superb scat solo

from the 1973 studio recording isn’t used at this point, when the band has such

accomplished sopranos at its disposal: as it was, the piano solo was a pleasing

placeholder but it did not attempt the architectural distinction of Christianne

Legrand’s memorable offering. The strings made a savagely precise job of seesawing

down into the finale, originally a 1973 piano-detail. The suddenly-slowing

end of this marvellous piece was greeted with immediate cheering: doubtless it

had been worthwhile warming up the audience’s vocal chords with the Last Night

of the Proms preliminaries. At this point I noted that Gary’s piano was slanted

further across the stage than it is at band-only concerts: this, I later learnt,

was intended to allow Geoff Dunn to coordinate his timing by watching the

Brooker hands, ordinarily visible over the top of a ‘knitting-machine’ digital

keyboard, but tonight concealed by the quasi-traditional glossy piano casework.

‘Thank you

very much,’ said Gary. ‘As you may have guessed slightly we have a little bit of

a theme in the first half here which … we play a couple from the Grand Hotel

album, which was 1973 I think. So – not long ago, really, doesn’t seem that

long anyway. Mind you, you had to be there, and if you were there you don’t

really remember it. It was like that. Here’s a little rock and roll one with the

orchestra … well, up-tempo, let’s call it.’

4

Toujours

l'Amour

Almost all

the songs on Grand Hotel start with solo piano; of course it was wondrous

to hear the piano rolling out the opening chords of this long-neglected classic.

Gary had not enjoyed playing the piano provided for rehearsal: it had had a

prominent scratch on it, and had been mixed to his monitors in mono. Another one

was provided – a tiny Roland e-grand as seen at Ledreborg – and it sounded

excellent. At the start of the song the orchestral tambourine provided

percussive colouring, and Matt’s fluid bass beautifully underpinned the mighty

ensemble, while Josh’s Hammond sang over the top. In fact organ and guitar shone

throughout this piece, on which any sound-balance issues seemed to have been

perfectly resolved. The choir, so confident and gospelly on those wordless

adornments, was a far cry from Grabham and Cartwright’s scranneling in the early

days. The song boasted Geoff’s first guitar solo in a while, and it was a good,

assertive one, steering close to the Grabham template and having the same sort

of warm, fat sound.

The second

‘French girl’ of the evening offered to ‘teach me to dance’, in what seems to

have become a permanent word-change from ‘give me a chance’

– it's the way Keith Reid published it in his

My Own Choice anthology. There was plenty of

intriguing snare work from Geoff Dunn, and Gary hollered an introduction to the

second guitar break, which was pure Whitehorn, right up to the top of the neck,

inventive and piercing, yet ultimately succumbing to the welter of

orchestration. The final handclaps, enthusiastically enacted by the choir, were

emphasised by the orchestral ‘whip’ (two planks joined by a hinge!) to great

effect.

‘Toujours

l’Amour,’ Gary back-announced. ‘As we’re in Denmark … it is nice to come to

Denmark now and again … I don’t think we’ve been for quite a long time [although

other nations may jealously suppose Denmark to be the prime arena for Procol

Harum shows, the band had in fact not played there since their four dates

in

November 2006]. We passed through early one morning on the way to

Tallinn a

couple of weeks ago, that was it. Managed to have an

Elephant Beer in the

airport, though [laughter]. Well, it was early! That’s a Danish breakfast, isn’t

it? [more laughter] Anyway this is … partly … to Hans Christian Andersen …

from Odense … who used to write little stories for kiddies … and adults … [by now

there was a constant undertow of amusement in the audience] … Have you read his

one, My Swedish Meatball? That’s very good [laughter peaks] … The

Emperor's New Clothes …’

5

The Emperor's New Clothes

This was the

evening’s only song originating in the present millennium, yet it started, like

the Grand Hotel numbers, with an assertive swirl of piano, before

yielding to a mood of mournful melancholy made only more poignant by the levity

that had preceded it. This was a new arrangement, by Nicholas Dodd, who took a

rather different approach from that of the Austrian composer Peter Skorpik,

whose orchestrated Emperor

may be heard on The Palers’ Project’s

second 2CD album, From Shadow to Shadow. Under Dodd, the strings come in only at

the first chorus, and the texture thickens, and there’s a touch of bell-tree, in

the bridge to verse two, while the Hammond rides over the top with a single,

judicious line. There was momentary trouble on stage in verse one from a

crackling amp, and afterwards Gary said that the offending instrumental lead

(‘cord’) would be stowed overnight in the ‘Roadies’ Healing Trunk’, whence it

would emerge for its next outing in perfect working order once more!

Brooker

changed the melody of the first chorus, giving it a more ‘horizontal’ contour,

and the vocal was excitingly fluid throughout: ‘squandered’ was interestingly

articulated and it all sounded very spontaneous and somehow ‘real’. The

orchestra warmed up further in the second, extended bridge passage: detached

chords from the strings dramatised the third verse, which featured a plaintive

oboe peeping through the texture before the other woodwinds summoned a downward

counterpoint. There was brass colouring for the final bridge, the guitar rose

and fell, and trumpets spoke out in a kind of funeral triumph towards the end

before everything fell away chillingly (Josh, who had felt the heat early, had by

now had put his tailcoat on again) to leave piano and organ under the soulful

vocal, and a solo trumpet in the coda to mark the end of the song. This number

earned the highest applause of the evening – thus far!

Brooker

changed the melody of the first chorus, giving it a more ‘horizontal’ contour,

and the vocal was excitingly fluid throughout: ‘squandered’ was interestingly

articulated and it all sounded very spontaneous and somehow ‘real’. The

orchestra warmed up further in the second, extended bridge passage: detached

chords from the strings dramatised the third verse, which featured a plaintive

oboe peeping through the texture before the other woodwinds summoned a downward

counterpoint. There was brass colouring for the final bridge, the guitar rose

and fell, and trumpets spoke out in a kind of funeral triumph towards the end

before everything fell away chillingly (Josh, who had felt the heat early, had by

now had put his tailcoat on again) to leave piano and organ under the soulful

vocal, and a solo trumpet in the coda to mark the end of the song. This number

earned the highest applause of the evening – thus far!

‘Thank you,’

said Gary Brooker, ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes.’ We must hope that

the next studio album – when it comes! – will contain freshly-written songs as

exceptional as this one. There are certainly grounds for believing that such an

album will one day be made: ‘Of course Procol Harum will make another

studio album,’ Gary explained to interviewer Frank Helenius in Aalborg, just

three nights after the present show, ‘… there are companies that want Procol

Harum to do that, and will help us pay for it.’ But the 21st century

band is working in the teeth of operational difficulties that they have never

faced before. ‘It’s actually much more difficult now,’ Brooker ruefully

emphasised to Helenius. ‘It was simple once. You made an album: nobody

had heard it until they went into the shop and bought it. Now, if you dare to

play a new tune on stage, it’s on

YouTube that night … it really spoils a lot of

it … If you have a studio album out, it’s got to be all done in secret, and I

think we’ve only just kind of realised that in the last year.’ It’s a sad

paradox that the pure enthusiasm of Procol’s most zealous fans is actually

holding back the new work they all long to hear; and that whatever the band does

eventually record will not have been developed and road-tested in front of live

audiences as it often was in less technologically-fluent times.

6 Homburg

I was later

informed that there had been a great deal more inter-song patter from the podium

on the previous evening, the opening of this Danish tour; but Homburg was

another song that began without spoken preface. In this rather soupy Nicholas

Dodd arrangement, the signature piano opening is missing, replaced by soaring

sopranos and shimmering pads of orchestral sound. This was all very nicely done,

and warmly received, yet isn’t really to my own taste: when I hear that Disney soundscape I can’t help visualising

the opening titles scrolling up a midnight-blue panorama, with hearthside

lights a-twinkle, as the camera tracks over CGI hills and far away, to home in

on some mournful yet winsome family of dispossessed badgers … a far cry from the

angst and alienation of Reid’s Homburg libretto. Procol Harum stood in

silhouette for the übersweet prelude, which the audience listened to in silence,

clapping only when they heard the word ‘multilingual’ (the same way that crowds

respond to ‘fandango’ when A Whiter Shade of Pale is played: it was part

of Reid’s early genius to sow a striking image – ‘Prussian blue’, ‘six-triggered

bride’ – in the opening moments of a lyric, and perhaps that’s one of the

reasons why the less-colourfully worded Quite Rightly So didn’t set the singles

charts ablaze). Gary sang the first stanza with piano and harp, and the band

joined him on the link into the second verse.

There were no

comic tick-tocks from the guitar in verse two, which is probably a good thing in

this context. Gary Brooker had declined to attend the

Procol Harum Project’s gig

at Copenhagen’s PH Cafeen that afternoon, because he was nursing a cold: later

he would declare that he had beaten it (though it would flourish afresh at the

Vejle shows) and there was certainly no audible evidence of congestion or vocal

distress on this occasion. As the song developed, and the movement in the

orchestration increased, Gary’s vocal performance grew ever more titanic. An

emphatic guitar-crunch mirrored ‘shudder’ (an excellent effect we first heard at

the Leamington Spa gig, Hallowe’en 2010) and it all ended splendidly.

The Copenhagen audience’s long applause, and cheering, cut in before David

Firman brought the orchestra off; at this early stage the standing ovation

involved just one person in the stalls, but later it would be very different. Of

course I love the original song, but I’d have traded the particular arrangement

for something with the subtlety and understatement of the orchestral

Strangers in Space, as heard with the Hallé in 2001, and not to my knowledge

played again since.

There were no

comic tick-tocks from the guitar in verse two, which is probably a good thing in

this context. Gary Brooker had declined to attend the

Procol Harum Project’s gig

at Copenhagen’s PH Cafeen that afternoon, because he was nursing a cold: later

he would declare that he had beaten it (though it would flourish afresh at the

Vejle shows) and there was certainly no audible evidence of congestion or vocal

distress on this occasion. As the song developed, and the movement in the

orchestration increased, Gary’s vocal performance grew ever more titanic. An

emphatic guitar-crunch mirrored ‘shudder’ (an excellent effect we first heard at

the Leamington Spa gig, Hallowe’en 2010) and it all ended splendidly.

The Copenhagen audience’s long applause, and cheering, cut in before David

Firman brought the orchestra off; at this early stage the standing ovation

involved just one person in the stalls, but later it would be very different. Of

course I love the original song, but I’d have traded the particular arrangement

for something with the subtlety and understatement of the orchestral

Strangers in Space, as heard with the Hallé in 2001, and not to my knowledge

played again since.

‘Homburg

… thank you. Homburg … thank you,’ said The Commander, stereophonically,

as if translating his own words from English into English. ‘Some of these

versions do end up a little bit different from the original singles or the album

versions, but that’s … what’s life’s all about. We hope we always keep the

essence of these songs that we do, and just expand them and make them more

enjoyable with a great orchestra and choir like this bunch here (applause) … and

it’s all of their birthdays today.’ He continued with a familiar trope to

introduce the raucous Simple Sister, a useful counterbalance to the mood

of the foregoing number. ‘This is a form of rock; I think it’s one of the only

heavy metal songs we ever did. And of course the drums start off as they always

do, nice and noisy. “We will rock you”!’

7 Simple

Sister

Immediately

the orchestra started walloping the back-beat, Brzezicki-style, and Geoff’s

guitar – at last released from its strait-tuxedo – came rasping in. The

uninhibited choir, intensely musical even when hollering bizarre Reidly

imprecations, let rip with full force. Meanwhile Josh left the stage,

escorted by the bellhop, there being no role for his organ throughout most of

this song.

This was a

Brooker arrangement, notably less enveloping than the previous number: he uses

many more holes and spaces in the texture, through which we seem to peep into

other soundworlds. At the ends of certain phrases he places gaps (as in

Bringing Home the Bacon) in which other instruments can have their cheeky

say. After the first guitar solo statements, the strings take the sinuous

lyrical theme, as heard on 1996’s The Long Goodbye album, which is very

expressive and almost sounds like a hurdy-gurdy in the hands of masters like

Nigel Eaton or

Pascal leFeuvre. Before long Matt Pegg is the featured soloist,

for the so-called

Cool Jerk

section: instead of the multi-tracked ‘mad pianos’ from the record we’re treated

to a hailstorm of xylophone (reminiscent perhaps of passages in

Brooker’s

ballet, Delta, which was written for the Royal Danish Ballet to première

in this very city, some twenty years ago). In the orchestra the double basses,

cousins to Matt’s five-string, join him on the ostinato riff. The strings call

the playful elements of the orchestra to order, and soon the trombones are

blasting out insinuating lines recalling Robin Trower’s original guitar

performance.

This was a piece

in which the rock-band / orchestral mix worked exceptionally well – clearly

something orchestrated by a man who thought in terms of overdubs adding colour

to the fundamental structure of the song – and the percussion section struck me

as the heroes of the hour. At one time or another we’d heard anvil, bells,

castanets, cymbals, glockenspiel, the Grande Caisse, marimba, tambourines,

tam-tam, five timpani, tubular bells, whip, wood blocks, xylophone and doubtless

plenty of other instruments. As David Firman told me, ‘The percussion section

play many instruments – the two players we use are especially versatile (and

busy) and manage to cover what otherwise might take four players to accomplish’:

he cited Simple Sister as a special example of this. Josh was escorted

back in for verse three, and contributed his fat Hammond sound to the final

chords, in which the choir also shone. As did Matt Pegg’s spectacular shoes,

which for some reason I noticed only now, as Gary shouted out, cutting through

the applause and mighty cheers, that the band would now be leaving the stage for

the intermission.

Because the

concert hall and hotel were all part of one complex, it was possible to nip back

to one’s room to get a drink of water, sharpen one’s pencil, and so on, avoiding

the queues for refreshment down below. Nonetheless it was delightful to meet so

many familiar faces in the foyer area, some perhaps unsurprisingly having

gravitated towards the merchandise stall (staffed in part by the ubiquitous

Andrea Ciccioriccio from Rome) where two new designs of Procol Harum tee-shirt

were for sale, as well as a good range of the excellent

new Salvo

reissue albums in all their remastered and bonus-track-laden glory. The icing on the

cake would have been a new Procol Harum album, of course! Pleasant as it was to

hobnob with Procol acquaintances from all over the world, it was of course no

disappointment to be recalled to the concert hall where, at 9.35 pm, Hans-Otto

Bisgaard again presented the band (‘Gary Brooker and Procol Harum’ following the

Sixties’ pattern of ‘Freddie and the Dreamers’ etc), who came on, in less dressy

attire, to deliver a less-formal, even more delicious set than we had witnessed

in Part One of this memorable show.

The icing on the

cake would have been a new Procol Harum album, of course! Pleasant as it was to

hobnob with Procol acquaintances from all over the world, it was of course no

disappointment to be recalled to the concert hall where, at 9.35 pm, Hans-Otto

Bisgaard again presented the band (‘Gary Brooker and Procol Harum’ following the

Sixties’ pattern of ‘Freddie and the Dreamers’ etc), who came on, in less dressy

attire, to deliver a less-formal, even more delicious set than we had witnessed

in Part One of this memorable show.

8 Something

Magic

Geoff Dunn’s

authoritative stick-clickings brought in the oriental bombast of the prelude to

this late Old-Testament song. As the verses began, flute doubled the upward

piano flourishes, and Josh supplied the gleaming arpeggiations from his Yamaha

Motif synthesiser, along with some judicious Hammond padding. Dunn’s drums were

as ever impeccable, and the whole ensemble sounded very much like the version

from the eponymous album. Up a semitone, and verse two introduced Geoff

Whitehorn’s harmony vocal: he blends so well with Gary that these unobtrusive

yet essential contributions perhaps don’t receive the attention and credit they

deserve. It was at this stage, however, that I first noticed that no vocal

microphone had been provided for Matt Pegg, and this confirmed, disappointingly,

that In Held ’Twas in I (in which Matt speaks Keith Reid’s ‘Held close …’

lines) was not to feature in the concert. At breakfast the following day Geoff

Whitehorn havered about this suite: he loves to play it, ‘… but it’s difficult;

at least, it’s not difficult, but it’s a very long while to be concentrating’ I

think is the essence of what he was saying. One might have expected to hear

In Held, since it’s in the band’s present repertoire, and had been played

fewer than ten weeks earlier during Procol Harum’s third encounter

with the

Edmonton Symphony Orchestra in Canada. But it would be ungracious to cavil over

omissions from the Danish concert programme, in view of what was yet to come.

During the

‘nightmares come to mock’ interlude it was obvious that Geoff’s Fret King Trevor

Wilkinson Corona, which he was now using, had more presence than the Les Paul,

in the current context. The strings, swirling and soaring, reminded us what a

good job Miami arranger Mike Lewis had done in illustrating this number,

programmatically, in 1976. The very formal structure of the song gives little

leeway for new interpretation and improvisation: it’s a good job it’s all so

substantial as it is.

9 Broken

Barricades

Another

title-track swept in after this, starting without preliminaries, but of course

immediately recognisable from that rolling piano motif. Josh Phillips provided

some harpsi-like sparkle from the Motif. As I recall, Gary went straight into

‘the seaweed and the cobweb’ in verse one, but it didn’t spoil things. It seems

likely that this was Brooker’s own arrangement, as heard at the

Hollywood Bowl

in 1973: David Firman described it to me as ‘a veteran score that DF edited,

adapted and amended especially for this tour.’ The choir entered in the middle

eight for the ‘whose husband’ section, at the end of which Gary’s concentration

seemed to waver briefly – the only moment of the show where one could have found

his otherwise astonishing performance wanting. Broken Barricades remains

a brief piece; perhaps three minutes, of which two are sung and one is the final

ostinato; as this came in there was some great extended bass-playing from the

dextrous and melodically-inventive Matt Pegg. Geoff Dunn got some interesting

cross-rhythms going, and eventually Whitehorn’s Strat came chain-sawing in.

There was great applause, although it was not a flawless performance: the spirit

of it had been exemplary, even if there had been glitches in small matters of

detail.

‘We’d now

like to do a Procol Blues song,’ said Gary Brooker. ‘This is based on pirate

tales and whaling stories.’

10 Whaling

Stories

The choir’s yell

(to what extent was this detail influenced, I wonder, by the famous choral shout

of ‘Slain!’ in William Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast – which Gary might

have come across in

Hoffnung's exceptionally short parody version (GB namechecks Hoffnung in the

opening moments of the Edmonton album)?) sounded as though

they had all been jabbed in the ribs, and there was immediate applause as it the

song started. Geoff’s guitar counterpoint to Gary’s vocal was razor-sharp; the

strings swelled in behind to ravishing effect and after a while I realised I’d

stopped writing things down. The band sidled in bit by bit, so one could never

quite say at what point the ensemble reach full intensity. Josh’s Hammond

underlined how ‘rum was served’ – what a different atmosphere to A Rum Tale,

Procol's other rum song! – and when ‘six bells struck’ a dedicated spotlight

picked out the anvil player at the back of the orchestra, using his two hammers

to deliver a left-left-right-right paradiddle, extremely slowly. As the rising

scale passage began, punctuated with savage power chords (from Geoff’s

Hughes

and Kettner Statesman 20 watt amp (‘turned up to about 2’ as he later claimed))

the goose bumps really started to set in. The choir seem completely committed to

the boiling oil and shrieking steam; the orchestra gave their all. Graham Ewins

at the sound-desk chipped in some telling vocal echo on ‘Not a man who had a

finger’. Gary screamed, and the guitar solo broke out, really fighting for its

place at the top of the tumult in the orchestra, where all the devils of hell seem to

have been released.

I’m not in a

position to compare this note-for-note with the Ledreborg arrangement, but, as

David Firman wrote, after the Aalborg show, ‘Gary is always looking to find and

finesse more detail – and I am too. Just today I fixed a couple of notes in

Barnyard Story, and checked an internal harmony in A Whiter Shade of Pale.

The instrumentalists and vocal ensemble get ever more confident as we progress

through each performance, and all of us are eager to search out ever more

colours, more contrasts, richer textures, crisper rhythms. Half the time I/we

can do this spontaneously (after all that’s what a conductor is supposed to do)

and note changes I can give out at our sound calls, or just mention them to the

players – the heads of sections for the strings etc.’ One might hope that an

official recording of this concert, or another in the series, will surface: at

the same time, one would have to concede that the emotional and physical effects

of hearing it, in the darkness of a sold-out hall, can never really be

recaptured on loudspeakers or headphones in a living-room or listening chamber.

Finally the guitar

quietened and the choir shadowed the insistent upward scale awhile, until the

peaceful ‘daybreak’ music supervened, with trickling woodwinds, which might

perhaps have been a little more languid. Someone whistled involuntarily in the

crowd – which was by no means a quiet ‘classical’ congregation – a moment before

the ‘Shalimar’s cut in. A very mobile Finnish fan in the row in front of me

exemplified the spirit of audience involvement that all on stage had conspired

to elicit: weaving and bobbing uninhibitedly in her seat, she seemed undecided

whether to succumb to a heart-attack or to sexual euphoria.

Finally the guitar

quietened and the choir shadowed the insistent upward scale awhile, until the

peaceful ‘daybreak’ music supervened, with trickling woodwinds, which might

perhaps have been a little more languid. Someone whistled involuntarily in the

crowd – which was by no means a quiet ‘classical’ congregation – a moment before

the ‘Shalimar’s cut in. A very mobile Finnish fan in the row in front of me

exemplified the spirit of audience involvement that all on stage had conspired

to elicit: weaving and bobbing uninhibitedly in her seat, she seemed undecided

whether to succumb to a heart-attack or to sexual euphoria.

Perhaps a tiny bit

more restraint of tempo at the finale would have made this a master performance?

Whatever, we had passed a wonderful eight minutes or so, and the audience – no

longer one person, nor isolated handfuls – gave another standing ovation. Gary

acknowledged Geoff, who received his applause with a comic wolf-whistle on the

guitar. It may not qualify entirely as ‘a blues’, but Whaling Stories

would surely rank as a majestic composition from anyone of any age: we should

remember occasionally that Brooker was 26 when he came up with this. And it was

puzzling, as the succeeding setlists came in to ‘Beyond the Pale’, to find that

this masterpiece was played at only three of the eight orchestral gigs on this

tour, ceding to the Reidless Symphathy for the Hard of Hearing – another

epic and episodic piece but not, to my mind, of the same structural daring or

emotional range.

11

Barnyard Story

Without any

spoken preliminary, Gary’s piano started to play the opening of the sombre

Barnyard Story.

The prospect of hearing, back to back, two of

the darkest tracks from Procol’s finest album, Home, reminded

Linda and me why it had been worth getting up somewhat before 4 am and

travelling the best part of a thousand miles to hear my fortieth show, her

thirty-second, from the same band. By a typical Procolian coincidence we’d heard

exactly the same song pairing played in that order by the Procol Harum Project,

earlier the same day, at their excellent tribute-band gig a few miles to the

south in the Danish capital.

Initially

it was just piano, voice and bass; then very sombre low strings joined

in (David Firman’s understated arrangement a far cry from the Hollywood

Homburg). A

twinkle of Hammond, decorating ‘once I stood upon Olympus’, reminded me of the

album recording of Magdalene (My Regal Zonophone); then the higher voices

in the orchestra swelled in to fantastic effect. The B3 and guitar presented the

quintessential Procol sound on the ‘last’ verse, after which Gary Brooker played

the ‘Chopin’ rhythm three times, his death march on the piano underscored by the

tubular bells.

Suddenly

Josh’s B3 played a glissando up into the once-unexpected guitar solo (already

the Procol Harum Project – influenced no doubt by the

Spirit of Nøkken

download-album version – are playing a guitar solo on their version of this

song); backed by wordless choir, Geoff’s guitar spoke volumes. The song then

lapsed back into reflective quietude, and Gary gave a very bluesy inflection to

‘my life seems pure’. The choir edged close to excess, and drew back: another

Procol hallmark. Muted brass underlined the final chord of a magnificent

performance of this once-neglected song that now, with its extended instrumental

section, has found its way to the centre of the canon. It was hard to see how

this concert could get any better.

‘Thank you,’

said Gary Brooker. ‘Don’t worry it’s not all dead gloomy stuff … there are

happier moments ahead. This next one, we’re going to rock off with the Dansk

Radio Underground Orchestra [laughter] … in Butterfly Boys. Join in if

you want to, ready? All blow your horns if you want to. Ready … one, two, three

…’

12

Butterfly Boys

Under the

cacophony of audience vuvuzelas (so now 1,000+ fans of the band can tell their

grandchildren that ‘I played with Procol Harum in Copenhagen’) the robust piano

riff to Butterfly Boys cut in and the song was soon under way. Gary

came up with a mild vocal remix in verse one, but it was of no consequence. His

is another exemplary arrangement, albeit of a different kind from what we’d

heard so far: little imaginative details bring the itching fleas to life, and

the score abounds with other effective and mischievous touches. A choir that

used plentiful operatic vibrato, to help their sound cut through an ensemble,

would have sounded incongruous and silly singing about groceries and cake: but

this choir, close-miked and singing without affectation, rode above any such

consideration. It could be my imagination, but it seemed that Geoff’s guitar

break started with an evocation of Andy Fairweather Low’s distinctive tone and

chording on the Long Goodbye recording.

In verse

two, Procol’s rhythm section revealed a new, impudent motif of emphasised sixth

and seventh quavers after ‘Put their fingers’ etc: one could imagine this effect

getting even sharper as the tour progressed. Josh was standing up to play, and

the leader of the orchestra exhorted clapping as the choristers all gospelled

away with compelling energy. In the second break Geoff offered a recklessly

‘uncivilised’ guitar solo, deftly knitting together many tricks of his

immaculate trade: a whammy-bar upward chordal glissando, lots of squealing

harmonics, lightning runs. Despite still appearing in at least token concert

dress (comically printed on his tee-shirt) he appeared entirely disinhibited

now. How interesting to find this song, relegated on its parent album to an

also-ran position near the end of side two, taking wing in the formal concert

setting! As its triplets wound up, wildly enthusiastic appreciation broke out

all around. The neophytes, it seemed, had become card-carrying converts.

‘Butterfly

Boys!’ shouted Gary, riding the applause. ‘Before we start the next one

let’s have a little chat, I think, calm down a bit. A bit over-excited there.

You don’t know what could happen, a man of my age [this was rich, uttered by the

sexagenarian who had been last man standing the previous evening, and who would

venture out into the frosty wee small hours after this show, foraging for a

take-away long after his younger fans had collapsed into bed]. Mind you, what a

place to go! If you’re going to go, onstage in Copenhagen is as good as

anywhere. But I don’t think I’m ready quite for that old wooden box [laughter].

Unlike some of my great friends that have passed that way. We’d like to play

this for all our friends who watch us from above, who … [and his voice assumed a

dark timbre] take the deep, dark travel through the waves of life. Ready?’

13

A Salty Dog

Of course, A Salty Dog was the song that followed, but I don’t remember

ever hearing it quite like this. It began with a version of the orchestrated

prelude by Darryl Way – formerly violinist with the excellent

Curved Air, and a

Brooker associate from the days when they played together on

a ‘Rock Meets

Classic’ bill under Eberhard Schoener – that we first heard on the symphonic

Long Goodbye album. Gary had invited Way to orchestrate Procol songs, having

been impressed by

Way’s Sting arrangements at the

Heineken Night

of the Proms in 1993 (read Way on Brooker

here). The links are manifold: Sting and the Police had been

‘house band’ to Schoener before they hit the big time, and their drummer Stewart

Copeland was married to Curved Air’s vocalist, Sonja Kristina. Curved Air’s

multi-instrumentalist Francis Monkman ('Robin Trower's

use of lead guitar over 'classical-style' backing was one of my first important

influences') auditioned

for Procol Harum at one stage too.

A nautical bell

rang in the orchestra, and a somewhat Stravinsky-like superposition of clarinet,

bassoon and low brass painted a sombre opening tableau. Darkly-voiced brass

developed the melodic contour of ‘no-one leave alive’; ’celli surged unrulily.

It was all very impressionistic and effective. The strings reached a plateau,

and the French horns stated the theme, competing tellingly against the

prevailing tonality: this was the first orchestral climax. When Maestro Brooker

hit the opening piano chord – one of the unmistakable sounds of rock music –

there was a brief burst of applause, but it wasn’t the real beginning of the

song as we know: in came the Danish choir, singing in Latin: the Way had been a

prelude to a prelude.

A nautical bell

rang in the orchestra, and a somewhat Stravinsky-like superposition of clarinet,

bassoon and low brass painted a sombre opening tableau. Darkly-voiced brass

developed the melodic contour of ‘no-one leave alive’; ’celli surged unrulily.

It was all very impressionistic and effective. The strings reached a plateau,

and the French horns stated the theme, competing tellingly against the

prevailing tonality: this was the first orchestral climax. When Maestro Brooker

hit the opening piano chord – one of the unmistakable sounds of rock music –

there was a brief burst of applause, but it wasn’t the real beginning of the

song as we know: in came the Danish choir, singing in Latin: the Way had been a

prelude to a prelude.

The Latin

text, originally the province of the Gary Brooker Ensemble’s version, was very

clearly enunciated, so, when that was done, the start of the nautical narrative

entered on to a stage already charged with suspense and emotion. I was surprised

not to hear a Bosun’s whistle … perhaps I missed it? Geoff Dunn played the drum

entry in verse one to perfection, and Brooker’s voice, rich, dark and

expressive, cracked slightly on ‘we sailed for parts’ at the start of verse two,

which was very affecting. Geoff Whitehorn’s guitar counterpoint was played with

great restraint, but Dunn’s fills in this second verse were extended in true BJ

style. During the instrumental interlude – which Gary has occasionally likened,

with characteristic self-deprecation, to the opening few notes of

Something Wonderful

from Rodgers and Hammerstein's The King and I –

the orchestral instruments

wisely didn’t double or clutter the piano line. All that was missing, to make

this a compendium of all Salty Dogs, was the late 70s double-length

instrumental, followed by the upward key-change – an embellishment nixed by BJ

Wilson, who enjoyed singing along as he played, but couldn’t reach the high

notes! The firing of the gun – thanks to the Grande Caisse – was rumbustuous,

the organ glissando up into ‘Now many moons’ suitably stirring. This magical

rendering of the great song provoked an immediate standing ovation again and a

full-throated roar of approval.

14

Conquistador

This was another piece

that was launched into without spoken preamble, the strings and solo trumpet

initially sounding exactly like the 1971 Edmonton recording. Geoff was now back

on the Les Paul, which he reported that he would happily have played all

evening, save that the siting of the volume pot means he can’t reach it with his

little finger, as he needs to be able to do in order to control the guitar’s

output on songs like A Salty Dog. At this stage the Les Paul, full and

fat, still sounded like part of the overall texture rather than cutting through

incisively. The orchestral kit player was busy – using some kind of small bongo

drum whose exact nature couldn’t be glimpsed from my seat – and there was

splendid colouring from the orchestral tambourine; but the lion’s share of

percussive kudos went to Geoff Dunn. When Geoff first played with Procol Harum

(Rome, Autumn 2006) he elicited a triumphant ‘He gets it!’ from his delighted

bandmates. If Geoff had already ‘got it’ at that early point, he had it in

spades four years on!

Suddenly all

went still, for the reprise of the introduction. In verse three Gary sang

‘Conkeestador’ in Hispanic fashion. The ensemble stopped at ‘only die’ for a

swirl of harp to peep through, and soon the fretmen were standing aside in

genial fashion to admire Josh’s lightning-fast organ solo, flash and fine and

cutting through the dense symphonic weight. It was noticeable, though, that in

this context both soloists had gone for speed rather than shape when their turns

came in the spotlight: such is the adrenalin flowing on stage, with such musical

forces at full-tilt. The writhing blonde head in the row in front of us

confirmed that Miss Sinttu from Helsinki had not, in the end, gone for

the heart-attack option. Maestro Brooker jumped comically when the orchestra

played a sudden ‘hit’: it was all far from the sober dicky-bow image with which

these five musicians made their entrance. The piece ended with emphatic chords,

and applause washed over the scene, like the sea in the song’s fine words.

‘Gracias,’

said Gary, as he often does after this song, adding another Spanish tag,

something approximately like ‘Saludos a todos’. There followed a string

of almost sotto voce off-the-wall conversational clips, a comically gruff

self-interrogation that was punctuated by laughter from the hall. ‘I’ll have a

tequila later. Got me in the mood, that one. Are we working tomorrow? Sunday?

Monday off! Oh, won’t be going to church then … I’ll do the laundry.’ Finally he

allowed himself to return to the musical programme: ‘Going to let Maestro David

Firman start off this next piece.’

15 A Whiter

Shade of Pale

We’re

accustomed to thinking of this as a slow song, given that it stood out for its

dignity in the hectic hit parade where we all heard it first. In fact, though,

it’s usually performed at quite a sprightly lick: not so tonight. The

bittersweet minor-key embellishment – by former

Curved Air violinist Darryl Way

– of the original few bars of Fisher organ-melody, setting out at a very stately

72 bpm or so, earned immediate applause. The orchestra built up the string

chords as if we were listening to a single enormous instrument pulsing with

increasing vehemence. The speed picked up once we were listening to Gary Brooker

and his piano, with the bassline coming from the orchestra: the effect was

fabulous. The crowd did indeed call out for ‘more’, and the strings slid in

midway, a polished largo. Gary, perhaps transported, offered us a minor remix:

‘Although my eyes were open, the waiter brought a tray.’ It’s impossible to

imagine that, however many hundreds of times he has sung this song, he can

remain unmoved by the majestic treatment it is given by this ensemble, and the

reverent enthusiasm with which it is received as its relentless geometry

unfolds.

As Way

wrote to this reviewer recently, ‘My approach to arranging this iconic track was

to treat it as a piece of classical music and arrange it in the style of Bach,

the composer who had been the inspiration behind the piece. I arranged the first

part of the song just using Baroque instrumentation, before opening out the

piece and bringing in the full power and majesty of the modern symphony

orchestra. So in effect, the arrangement travels across time, in the same way

that the original song does.’

As Way

wrote to this reviewer recently, ‘My approach to arranging this iconic track was

to treat it as a piece of classical music and arrange it in the style of Bach,

the composer who had been the inspiration behind the piece. I arranged the first

part of the song just using Baroque instrumentation, before opening out the

piece and bringing in the full power and majesty of the modern symphony

orchestra. So in effect, the arrangement travels across time, in the same way

that the original song does.’

But that’s

not the only way Darryl’s vision travels across time: in this version it finds

space for the rock band that is notably not present on The Long Goodbye

recording.

There was applause for the entry of the Hammond organ, bass and drums, and

understated guitar. The choir joined in with the Vestal Virgins (in later

concerts there were indeed sixteen of them, though tonight one was absent, I

noticed). And in the rubato before the chorus, it was interesting how

fixedly David Firman watched Gary for the rhythmical lead. I asked Firman how

this responsibility was typically divided, between his band and Gary’s: ‘For me

it’s always about maintaining focus,’ he responded, ‘and giving each performer a

clear line of sight as to what he/she needs to do/needs to listen out for. They

must first of all be clear where their attention should be – initially that’s

me, but as they listen to the group I invite them to “catch the vibe” too. But

the line of responsibility should always be clear. I’m a conduit through which

the “symphonic” resources come to the party. If they are unclear what to do it’s

my responsibility to clarify and concentrate their energies – and ensure that

the interface between group and symphony folks is living, breathing, pulsating

and always inseparably intertwined.’

This degree

of sympathy between conductor and bandleader must explain in part why the

Harum/DR collaborations have been so immensely successful. And in this instance,

the sympathy of the arranger with the material is also crucial. As the Curved

Air violinist writes in his (unpublished) autobiography, ‘… [Brooker] told me

that he had an album coming up of Procol Harum tracks that would be performed by

the LSO. He enquired whether I would like to do a couple of the arrangements and

gave me the choice of what track I’d like to arrange. Without hesitation I

replied, “Whiter Shade of Pale, please”. “Damn,” he said. “I wanted to do

that one myself, but no problem, it’s yours.” I was immensely honoured to be

trusted with such an iconic track and one that had been so influential on me

when I was younger.’

Towards the

conclusion of A Whiter Shade of Pale the plucked double basses were

having a lot of visible fun, not least where a new small detail was concerned:

although the harmonies can be found entirely on the white notes of the piano,

the present arrangement supplies the basses with the occasional downward

semitonal step between D and C – as I recall, this was exactly where

David

Knights used to do the same thing in the very first line-up, and it had the same

peppery effect.

This was to

be a two-verse version of the Procol signature anthem. As Josh’s Hammond took up

the reins after the second chorus, the exultant inversion of the Fisher organ

theme was arguably rather compromised by being doubled on keening strings, and

the whole thing came close to overkill at the very end, with the stratospheric

choir weaving a countermelody leading into the mighty cadence – no piano cadenza

this time. But that’s the thing with Procol Harum: close to overkill perhaps,

but not quite there: they might occasionally nudge at the envelope of kitsch,

but they never quite rupture the membrane!

Procol Harum

left the stage triumphant … we clapped for three minutes or so, and brought

their leader back in on his own. ‘Thank you so much, ladies and gentlemen,’ Gary

began, ‘It gives me a great honour to come back on here … I can’t remember why I

came back now … I know what it was … I would like you to show a great Copenhagen

appreciation for what is one of the most marvellous orchestras, and just think,

they come from Copenhagen, how nice could it be? Ladies and gentlemen, the

Danske Radio UnderholdningsOrkestret! [He didn’t even venture a comic

mispronunciation of the name on this occasion]. And to make them sound even

better, please … the Danske Radio Vocal ensemble. Thank you! And the man who

pulls it all together, and makes us fit with the orchestra, and vice versa, is

the great Maestro conductor, Mr David Firman … please! Thank you Maestro.’

But there

was more to come before any encore could be played: ‘And what about Procol

Harum? On the guitar, Geoff Whitehorn! On the drums, Geoff Dunn – “In for one,

Geoff ‘Baby-face’ Dunn”. And on the bass, young Matt Pegg, all the way from

Eastbourne. On the Hammond organ, one of the greatest musicians in the country

(in the town he’s not so great): here he is, Josh Phillips!’ And finally Geoff

Whitehorn took the microphone briefly: ‘Ladies and Gentlemen, the reason we’re

all here. My favourite musician, probably: Gary Brooker, MBE!’

16

Into the Flood

16

Into the Flood

By way of an

encore, Procol Harum showcased the ugly duckling of their 90s’

repertoire: Into the Flood was released in Germany (October 1991)

as an unpolished – though promising – bonus track (still featuring demo

musicians) alongside

The Truth Won’t

Fade Away.

Its development into something elegant and voluptuous far outstrips that of any

other Procol song I can call to mind. Drumstick clicks and a raucous Les Paul

bottleneck glissando heralded that fluent bassline and Gary’s ardent declamation

of Reid’s staccato mosaic of narrative fragments, compiled in an interesting New

Testament style that – though seeming much less allusive than, say, Whaling

Stories – defies precise interpretation.

With its

call-and-response vocals the song reminded me strongly of the Motownish finale

to the Barbican gig, I’ll be Satisfied (so good they played it twice!).

The little five-note descending organ hook, repeated in the orchestra, is just

one of many band details that delight in the lead-up to the sea-change, when the

rock instruments are stilled and the choir begins its Gloria in Excelsis,

adapted from Mozart’s

Coronation Mass

– which

the Procols all turned to listen to: in this section the choir sounded a good

deal more ‘operatic’ than in all the foregoing items, as is required. Oddly, the

orchestra didn’t make as much as I’d have expected of the Beethoven’s Fifth

quotation that ends the choral interlude and heralds the frantic semiquavering

of the ‘hoedown’ section element, incorporated from a Wilson Pickett arrangement

made by Mathias Weiss (the Hammond organist who played Procol music alongside

Gary on 1993’s orchestral ‘Rock Meets Classic’ tour).

The strings were

absolutely on top of this demanding material, and the crowd clapped along.

Although during orchestral gigs Geoff Whitehorn suspends the

ensemble-coordinating role that he frequently fulfils in the five-piece setting,

he did revert for a moment, to cut the clapping expertly on the very moment that

a blast of tam-tam concluded the hoedown and brought Procol Harum in again. It

was an exuberant performance from an exuberant band, Gary Brooker so much in his

element, hollering gnomically with his devoted team playing at full pelt. ‘Come

on,’ he exhorted at one point, and the audience’s clapping resumed. Grand

Finale had been the show-closer the night before; but, much as I admire that

piece, I was delighted to hear Into the Flood instead.

But time

had run out.

‘Tak

og god nat,’

The Commander ventured in bold Danish, then lapsing into his native tongue he

translated for the benefit of the international brigade,

‘You’ve been a

lovely audience, we love it, thank you very much. Thank you to everybody.’ A

fully-satisfied audience took its time to leave the auditorium; and not long

afterwards Gary, like the rest of the band, appeared in the hotel foyer, also in

exceptionally contented mood, to burn some midnight oil with a hard core of

local and international fans; as noted above, he was still shining brightly by

the time most of us had been forced, by the rigours of a long day, to head up to

bed.

The equally

tireless David Firman had justly taken his place amid the Procols for the final

bow; his schedule, on concluding the eighth show of this Procol tour, was to see

him fly back to Heathrow, before dawn, to conduct a 10 am studio session with

the Royal Philharmonic. After two heavy days at Angel Studios in Islington he

was due back to Denmark for a Wednesday-morning rehearsal of The Danish Royal

Opera’s

My Fair Lady at Copenhagen’s Royal Theatre. Following that he

rejoins the RPO at the Albert Hall, before returning to Copenhagen to conduct a

commission he wrote for the Danish Royal Ballet, about to be revived for its

fourth season. He nonetheless found time to write to your correspondent with

these words about the wonderful collaboration between his symphonic platoon and

the electric hooligans of Procol Harum: ‘All the performers (especially

including DF) are touched by Gary’s instinctive and unique musical style, his

natural and sympathetic musicianship, and his generous inclusion of all of us in

his performance.’

I think we can

fairly conclude that a worldwide audience feels the same way too.

Bravo!

For

Procol’s Danish orchestral tour, an unbelievable 39 years and 20 orchestral

shows later, everything was much more polished (if also more predictable). These

days rockers and readers collaborate without inhibition, and indeed the average

age of the band probably exceeded that of the orchestra. Though there was no longer any barrier of

prejudice to demolish, the programme was similarly constituted. This being a New Year concert series, the intention of

the opening, non-electric numbers was evidently to put people – fresh in from the freezing,

misty streets – into a mood of happy celebration. Consequently the brief

prelude to the main attraction had been designed to imitate certain features of the BBC’s renowned

‘Last Night of the Proms’: highly varied, accessible music, with a good element

of audience participation. It soon became apparent that the sell-out crowd had

come to the

Falconer Centre in Frederiksberg – a classy city that stows away

inside Copenhagen itself – determined to enjoy itself.

For

Procol’s Danish orchestral tour, an unbelievable 39 years and 20 orchestral

shows later, everything was much more polished (if also more predictable). These

days rockers and readers collaborate without inhibition, and indeed the average

age of the band probably exceeded that of the orchestra. Though there was no longer any barrier of

prejudice to demolish, the programme was similarly constituted. This being a New Year concert series, the intention of

the opening, non-electric numbers was evidently to put people – fresh in from the freezing,

misty streets – into a mood of happy celebration. Consequently the brief

prelude to the main attraction had been designed to imitate certain features of the BBC’s renowned

‘Last Night of the Proms’: highly varied, accessible music, with a good element

of audience participation. It soon became apparent that the sell-out crowd had

come to the

Falconer Centre in Frederiksberg – a classy city that stows away

inside Copenhagen itself – determined to enjoy itself.