Chris 'The Grouts' Michie

The Tape-Op tells his tale

We present a BtP e-interview with Chris Michie, now Technical Editor of Mix

magazine, one time Tape-Operator on some crucial

Procol recording sessions. This interview is a prelude to the unveiling of

several more good pages from Chris, which reveal some intriguing background to

the band's seventies' sessions, much of it hitherto unknown.

We'd like to thank Chris specially for putting a lot of thought and

care into these recollections, which we know Palers will very much enjoy.

RC

Procol Harum fans who recognize your name from the Exotic

Birds and Fruit album know you,

for better or worse, as Chris ‘The Grouts’ Michie. Can you tell us how that

sobriquet came about?

Chris Michie

The ‘Grouts’ credit on Exotic Birds and Fruit is a reference to tea.

Mick Grabham was probably the original author – 'Cuppa grouts, Chris?’ It’s

probably a Northern term. 'Polly' Punter was another nickname that came out of

those sessions, though I can't remember what prompted it. Punter had a cheerful

and effusive personality and was quite a flashy dresser – he had a fondness

for platform shoes, which we dubbed 'Punter boots'. Also, when listening to

playbacks at the end of a session we would occasionally risk permanent hearing

damage by turning up the control room monitors to "Punter level," a

setting that few mortals could stand for very long. But hearing The Idol

through four 15-inch Tannoy Golds, each powered by a Quad 303 amp, was a

memorable experience.

You’re listed as providing ‘Comic Relief’

on the back of Broken

Barricades. You must have had a

great rapport with the band?

Procol Harum sessions were great fun for me. Chris

Thomas and John Punter were a relaxed and highly competent team, and I was a

rather undirected, head-in-air tape-op with ambition but no work ethic, so I

just amused myself and the band. At some point I taught some of the band

backgammon, which passed the time during overdub sessions, and I was often

engaged in a certain amount of verbal jousting with Keith,

the most articulate of the bunch. And I made gallons of tea.

Gary was humorous, though sometimes terse, Barrie

was a genius drummer who astounded on every take, Chris

was dryly amusing and an authority on Real Ale, and Robin

turned me on to BB King. I also remember going back to Gary’s house in St.

John’s Wood and hearing Leo Kottke’s first

album for the first time.

Can you remember when that was? There’s a

certain uncertainty at this website about how

Procol got into Kottke and when.

I think it must have been during the Broken Barricades sessions,

though it could have been in February '72 during the aborted first set of Grand

Hotel sessions. The 1st (Takoma) Kottke album release date would

probably clarify that. I got the impression that a US promoter had stuck Kottke

on the bill and the band liked him so much they asked for him to be their

support act for the rest of the tour.

What other music were the band-members into at

the time you knew them best?

Gary had pretty eclectic and sophisticated musical taste (he would rumble on

about Bruckner) and BJ had great taste too. Chris Thomas tells the story of

spending an evening drinking with BJ in some redneck bar in the US and listening

to the hardcore country music jukebox all night. This was back when the only

C&W music heard in the UK was in East Anglia (a hotbed of Jim Reeves fans)

and on the Byrds and Flying Burrito Bros. albums.

Robin helped encourage my white boy blues enthusiasm by telling me to listen

to BB King’s Three o’Clock Blues, and the Live at the Regal

album. I duly snapped up a double LP compilation of King’s singles for the

Kent label and a UK budget re-issue of the Regal LP, probably on Starline. As a

Marquee Club regular and self-absorbed record collector, I was fairly serious

about "getting" the blues and had already discovered Buddy Guy and

Howlin’ Wolf, probably by reading Eric Clapton interviews in Melody Maker.

Being older than me and professional musicians, the former Paramounts really

knew the music, so references they might have made to old Coasters records

probably would have gone over my head. But it might have been them who turned me

on to King Curtis and I know I bought Donny Hathaway’s Extension of a Man

LP on somebody’s recommendation – Robin’s, perhaps? I bought records

fairly consistently during my days as a tape-op at AIR, but really went nuts at

the end of my first Pink Floyd US tour – I took all my back wages down to

Tower Records or Sam Goody’s and loaded up on a suitcase full of vinyl. US

records were then about three dollars, which made them about one pound, five

shillings and I figured that as long as they weren’t shrink-wrapped I wouldn’t

have to pay duty. I almost detached my thumb nail by using it to open up about

sixty shrink-wrapped albums the night before my flight home. But I don’t know

if there was much in that particular haul that I picked up because of Procol’s

influence. Perhaps Weeds, the second Brewer & Shipley album, which I

think BJ had discovered, and maybe a Charles Mingus album (Oh, Yeah) that

I can’t remember listening to much.

When had you first become aware of Procol

Harum?

Like everyone else on the planet, I heard AWSoP

all through the summer of '67, in my case over the pirate radio stations moored

off the East Anglian coast (who can forget John Peel's Perfumed Garden and

the Johnnie Walker show?) and also saw a couple of TV appearances (Gary wore a

caftan). My best friend, whom I'd known since I was four and he was seven, went

to Canada that summer to drive a combine harvester and then went on to San

Francisco, where he briefly lived in a hippie commune, experienced the free love

phenomenon (very jealousy-inspiring) and came back with a pile of hip new

records. One of them was the first Procol Harum album,

and we spent much of the Christmas holidays listening to it on his family's

Philips "brown box" record player (it was a common autochanger model,

finished in a dark brown veneer, and only put out decent bass response when you

put the lid down. Mono, of course). I was pretty snobbish about pop music at the

time and tended not to buy anything that a friend already had, but I loved the

sound of the record and the guitar-playing and later overcame my initial

resistance and found a used reissue of the first album (on the Fly label?) in

Goldhawk Road. I now realize that the LP we had been listening to (reprocessed

stereo, with AWSoP added) was not available in the UK, but at the time it

was just the best of the records that my friend had brought back, narrowly

beating out Surrealistic Pillow. It's still my favorite.

What can you remember about the Procol Harum

recording sessions that you worked on?

I can answer that in two parts – the technical details of the recording

sessions, and what I can remember about how certain tracks evolved. I worked as

a tape-op on all of the sessions for Broken Barricades, Exotic Birds

and Fruit, and Robin’s Bridge of Sighs album [details

here] I also worked on at least some of the mixing sessions for the Edmonton

album [details here],

which was probably mixed at AIR in late '71, early '72. There was some reason

why I didn’t work on all of the Edmonton mix sessions – maybe I had some

sessions of my own as a recording engineer – and I think that Steve Nye

probably replaced me. However, when Procol returned to AIR for the first Grand

Hotel sessions I was back on the team, at least until mid-February 1972,

when I left AIR. I think the sessions were abandoned soon after.

In what state did Keith and Gary present

material to the band, and how did things evolve during work on a track?

As a tape-op, I was only involved in the studio-based activities, so I can’t

shed much light on the songwriting and arranging process. Chris Thomas would

have met with the band to help work out song arrangements before they came into

the studio and also would also have discussed the recording process ahead of

time with John Punter. I might have been asked for my opinion now and then

during sessions, but I doubt that anyone paid much attention to my response.

However, I do remember some bits specific to certain songs from Broken

Barricades [details

here], Grand Hotel [details

here] and Exotic Birds and Fruit [details

here].

Did you have any other Procol involvement?

My first job was at Central Sound, a 4-track and mono demo studio in Denmark

Street, London’s Tin Pan Alley. Sometime in 1969 Dave Knights came in with the

band he was managing and/or producing, Mickey Jupp’s

Legend. I can’t remember what they did or if any of it wound up on the Legend

albums, but I later discovered that Jupp was from the same Southend scene as The

Paramounts and that Procol knew him well.

I used to think that I had been present for the Liquorice

John Death remix sessions, and Chris Thomas’s notes on the released CD

indicate that that was quite possible. I was the seventh employee taken on at

AIR and the only tape-op on staff during the teething period in summer 1970

before the studio officially opened for business, so it is likely that I tape-op’ed

for the LJD remix sessions, which would have been done very fast – one or two

run-throughs and then a master mix for each song. The engineer, unless Chris

Thomas mixed it himself, would have been Bill Price. We often used to play back

the LJD tapes at the end of Chris Thomas and / or Procol Harum sessions – the

tapes were kept in the AIR

tape store for years.

How about live work?

Some time before Robin left the band I saw them play at Oxford Town Hall –

I think we all (Thomas, Punter, myself) drove down from London to see the show

and then drove back. Also, I was in Los Angeles in the summer of 1973 and saw

the Hollywood Bowl show from the front of house mix position. As with the

Edmonton show, the orchestra had difficulty keeping up with the beat, but it was

a decent show. As explained by Dave Pelletier elsewhere

on this site, Chris Thomas had a miserable time mixing the show. As I

remember it, the orchestra mics were pre-mixed in the recording truck and then

sent out to the front of house mix position as a submix. No problem there in

theory, except that in practice any changes in the truck upset the balance in

the house. Even a small change in the level of the string mic submix had the

result of sending the main PA into feedback. [read

about the orchestral sound-engineer at this concert]

|

|

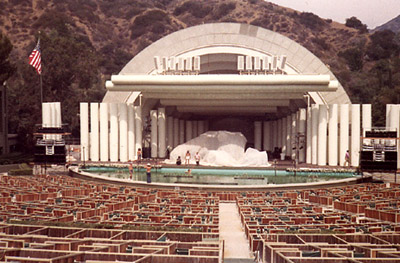

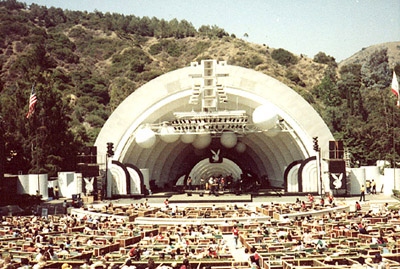

| The Hollywood Bowl during

setup for Pink Floyd’s concert on 22 September 1972. The 3-way

Kelsey-Morris PA consists of Martin bass bins, radial and multicell horns

with JBL drivers, and "bullet" supertweeters. The top row of

horn / tweeter boxes was added for this show in order to supplement the

system’s high frequency output, compensating for the very long throw to

the rear of the Bowl.

It was during sound check for this show that I pointed

out to the band that a section of Dark Side of the Moon, a piano

instrumental by Rick Wright, bore a striking resemblance to part of In

Held 'Twas In I. This did not go down too well (I had also pointed out

that Medicine Head had already used Dark Side of the Moon as an LP

title), but the band later changed the piece. The original section can be

heard on a bootleg from the February '72 Rainbow concerts. — Chris

Michie

|

|

|

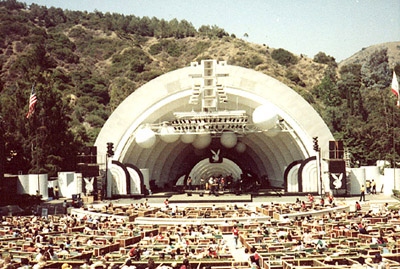

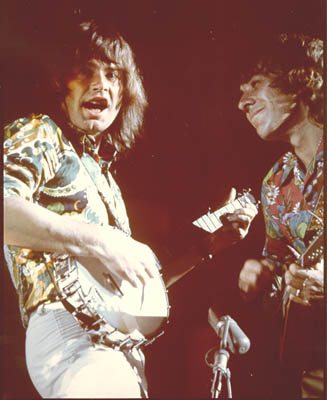

| The Hollywood Bowl during a

Playboy Jazz Festival, 1979, '80 or '81. The PA is a McCune Sound system

consisting of four full range JM-3 cabinets and one JM-7 subwoofer per

side. Note the innovative spherical acoustic reflectors within the band

shell and the new house PA cluster above the proscenium, both designed by

George Augspurger, I believe. |

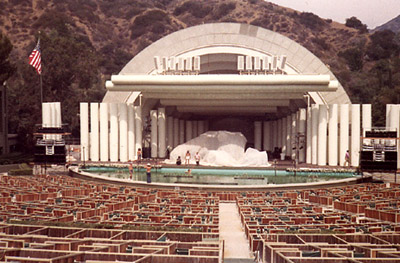

Another shot of the

Hollywood Bowl during a Playboy Jazz Festival in the early '80s. This

McCune Sound PA system consists of one (!) JM-10 cabinet per side. These

immensely powerful and clean full range integrated systems were originally

developed for stadium shows and are the ancestors of Meyer Sound’s

MSL-10 systems. Note further additions to the house PA cluster. —Chris

Michie |

Dave Pelletier was the band’s soundman and was responsible for the

technical aspects of the show, though Chris Thomas mixed whenever they could get

him out on tour. I think I’m correct in saying that Dave was using a Tycobrahe

sound system, which was made up of integrated three-way cabinets, rather than

the more traditional stacks of bass bins, horn boxes and tweeter arrays. The

integrated approach was the way of the future (I later moved to the U.S. in

order to work with McCune Sound’s John Meyer-designed JM-3 systems, the Gold

Standard of '70s integrated sound systems), but I’m not sure that the

Tycobrahe system was a particularly successful implementation. I had used a

Tycobrahe system on the first leg of Jethro Tull’s 1973 Passion Play tour

and wasn’t much impressed by it. But the PA was the least of my problems on

that tour, which was a technical and logistical nightmare – fortunately I got

fired after the first three weeks.

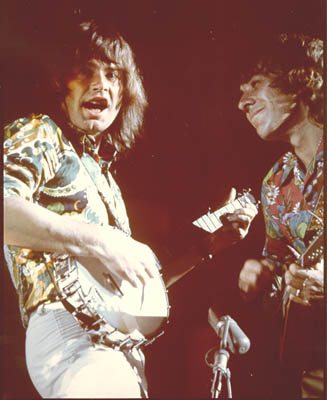

Incidentally the mic that Chris and Barrie are shown sharing is a quality

condenser mic, a Sony C-36 or C-37, popular then and now as a studio mic for

strings. Though quality condensers on stage are common now (I think Charlie

Watts was miked with large-diaphragm Neumanns for the last Rolling Stones tour),

they are much more sensitive to feedback than the more robust, less technically

complicated (no phantom power needed) and cheaper dynamic mics that are the

staple of live sound. If Chris Thomas and Dave Pelletier were using mainly

condensers on stage, they would be much more vulnerable to feedback, especially

if the mics got moved out of position. When mixing sound for orchestras outdoors

in the late '70s and early '80s for McCune Sound I typically used Shure SM56s,

bog standard dynamics (and John Lennon's favorite vocal mic). The loss of high

end was a fair trade for better gain before feedback and resistance to wind

noise. Indoors, of course, one could use condensers more easily and for Burt

Bacharach's string section we typically used some early Sony electret

condensers, battery powered and relatively cheap.

What were you doing in the final Procol years?

From 1976 to 1978 I was working as a freelance sound engineer in London. I

dug up a diary from 1976 that mentions a

one-off Procol show outdoors at York on Sunday, July 4. Apparently I went to

a Frankie Miller gig at the Victoria Palace the previous Sunday and "Procol

want me to mix at York next week." My diary notes that I attended two

rehearsals in the intervening week, taking time off from my "real" job

of driving a minicab (not a career high-point): at EZ Hire on Tuesday 29th June

("Not very enlightening, so left about 6 pm.") and another at

Manticore on Thursday 1st July. ("OK, but hard to tell what was going on in

Manticore. A couple of new numbers.") The two rehearsals were certainly not

for my benefit alone (though the Manticore rehearsal would have included a full

PA), and seem a bit unusual for a one-off gig; maybe the band had been scheduled

to start a tour soon after the York gig. Manticore was the former Fulham

Broadway cinema that Emerson, Lake & Palmer had bought for their own

rehearsals and rented out to other bands. It was dark and cavernous and didn't

sound too good. Also, it was usually cluttered with ELP's gear, unless they were

out on tour.

The gig itself was outdoors in a meadow, with York castle or some similarly

ancient ruin as a backdrop. My diary notes "Boring set up so went to York

Minster – lovely. Sound check not v. amazing. Procol’s show good. Took a

while to get comfy but ended up good (set-list here)."

According to the diary, I drove to and from York with Steve and Eddie, Procol's

roadies, though I distinctly remember discussing my fee with Keith while he

drove us at alarming speed up the motorway in his Bristol. "You've been

talking to yourself too much," he said and halved it to 50 pounds. He was

right, of course (at least about talking to myself too much). But I really

enjoyed mixing them – they were one of the great live bands. Like Pink Floyd

and King Crimson, they fully understood the power of dynamics (soft to loud and

back again), a valuable dramatic effect that far too many bands ignored, then

and now. Keith complained that I didn’t mix them loud enough, but by that time

I’d heard the same comments from managers everywhere – they all think that

louder is better because it makes the kids jump up and down. [In fact, Denny

Cordell came up to the mix position at the Rainbow

Theatre during Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers’ first UK tour and asked

me to turn it up. I knew the Rainbow fairly well and pointed out that if it went

any louder, the room would start to distort. (This isn’t an accurate technical

description of what happens, but anyone who’s mixed in the Rainbow knows what

I mean.) "Great!" said Cordell. "Distortion! That’s what I

want!"]

I also have a vague memory of the Procol’s

Ninth sessions with Lieber and Stoller. I had long since left AIR by

that time, but it may be that I met with the band at the studio before I mixed

them live at York.

And that was it, then?

Sometime in the '80s I called Keith when I was in New York. I met him at his

downtown apartment and we went to a nearby Italian café in Chinatown, I think,

and ate those exotic Italian pastries that show up in Godfather movies.

And I last saw Procol in San Francisco during the Prodigal

Stranger tour (they were mixed way too loud), and a few years ago I

caught a glimpse of Robin when he joined Bryan Ferry on stage when the Mamouna

tour came to the Bay Area.

And now you live in America?

I’ve lived in San Francisco since 1978 and worked as a sound engineer until

about 1984. Rather amazingly, I ran into Procol’s Tour Manager, Barry

Sinclair. He had been working as a scenery artist for Bill Graham Productions (I

think he had started out doing fairground painting in Southend before joining up

with Procol) and had by then branched out in to in-store displays. I’ve since

lost touch with Barry, but still see his car on the street (we live in the same

neighborhood). It was Barry that told me of BJ’s unfortunate fate.

I have very fond memories of Procol Harum and that all-too-brief period when

I worked at AIR Studios. Though I didn’t realize it at the time, I was in an

enormously privileged position. I was working at one of the best studios in

London and was rubbing shoulders with (and making tea for) some of the most

talented and successful people in the recording industry – George Martin, Chris

Thomas, Bill Price, John Punter, Jack

Clegg, Tony Visconti, Gus Dudgeon, Peter

Sullivan, John Burgess, Cooke and Greenaway, Dave Harries, Geoff Emerick, Steve

Nye, Stevie Wonder, Pink Floyd, to name only a few.

As I later discovered, working at a less than top-flight studio was a lot

less fun and few of the groups I subsequently worked with were as musically

rewarding or as personable as Procol Harum. They were friendly, amusing, and

extremely tolerant of a young and spoiled ex-public school boy with far too high

an opinion of himself. I wound up working for a number of bands who were more

successful in terms of record sales (Pink Floyd, Jethro Tull, Roxy Music,

Blondie, etc.) but I’ve always been very proud of my somewhat peripheral

association with Procol Harum and I have nothing but positive feelings about

them and their music.

Thanks, Chris!

Index for Chris Michie pages