Procol HarumBeyond

|

|

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |

|

BtP e-talked to Chris Michie, Technical Editor of Mix magazine about the recording of one of Procol Harum's most consistent albums …

The sessions for Exotic Birds and Fruit started in late 1973. The tracks were recorded and mixed in AIR Studio Two, though there might have been some overdub sessions in One (the big room) or Three (a mixing room with a small overdub booth).

I had been away from AIR for about nineteen months, during which time I'd toured Japan, the US and Europe with Pink Floyd, had toured the US briefly with Jethro Tull, and had also worked at two other London studios. I now had the perspective to realize that the job I'd left at AIR was better than most other studio jobs out there and I was very pleased that studio manager Dave Harries was willing to rehire me. I was even more pleased to discover that Procol Harum were coming back for another album.

AIR had gone through some technical changes in the time I'd been away and had upgraded from 16- to 24-track tape recorders. The Neve consoles had been changed as well, and now featured more extensive EQ (some engineers preferred the earlier models) and a monitor section that included faders, allowing the monitor levels of different tracks to be adjusted without affecting the recording levels (the older Neves had rotary pots for the output bus monitor sends, but the faders were better and more useful). The 3M 16-track recorders had been replaced by Studer 24-tracks and the Dolby systems had been much miniaturized and now switched automatically between record and play modes on a track-by-track basis. At some point Studio Two control room was remodeled for Quadrophonic monitoring, but that may have still been in the future in late '73. Like Studio One's control room, Two's control room was on the outside corner of the building (the NW) and looked out over Upper Regent Street. Unlike Control Room One, Two was more or less rectangular, and had no plinth raising the console above the studio floor level. At the back of the room were some low couches, and it was here that I taught some of the band to play backgammon, which I had learned in Lindos on the island of Rhodes during the two-month holiday that Pink Floyd had awarded themselves and their road crew the previous year.

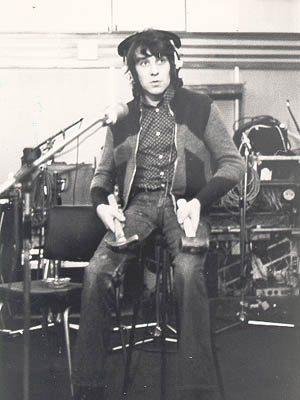

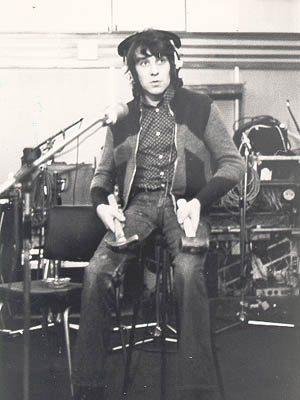

As with Broken Barricades, the sessions progressed fairly steadily through about two weeks of backing-tracks, a week or two of overdubs, and a week of mixing. Studio Two was smaller than One, though it had two overdub booths and a drum cage (black square tubing again). But it was a large enough studio for most band sessions and could accommodate fair-sized string sessions: the string overdubs for Nothing But The Truth were recorded in Two. The picture of BJ with the hammers, here and elsewhere on the site, shows the studio walls, which were covered above head height in rectangular sound absorptive panels, designed I believe by studio manager Dave Harries.

Though the furthest studio from the facility front door, it was the closest to the canteen, which was upstairs. During the day, the canteen was staffed (I think the tea lady's name was Cathy) and tea-orders for band sessions were generally filled only after the needs of other more "traditional" sessions had been met. In the evenings and at night the tape-ops made tea for their own sessions, so tea-breaks became more frequent.

The mood in the studio during the album was cheerful and productive, though I think that the band morale was in decline. Alan and Mick fitted in well and the group had, I think, been fairly successful on recent tours, in part thanks to the success of the last two albums. But I also believe that they all felt that they were unlikely ever to achieve the commercial success that they deserved. BJ was showing signs of alopecia and, once the backing tracks were finished and he had little to do, sometimes came back from the dinner-break drunk - Chris Copping was his usual drinking partner.

Apart from New Lamps for Old, which was recorded and mixed in a day near the end of the sessions, all of the other backing-tracks were recorded uneventfully. I think Drunk Again must have been recorded with the rest of the album and then effectively bumped into B-side status when Gary turned up with New Lamps for Old. Some tracks were more difficult - The Idol and As Strong As Samson probably each took more than a dozen takes - but progress was steady. After three studio albums together, Chris Thomas and the band were skilled and efficient and moved quickly and smoothly from the outline of a backing track to the fully fleshed-out finished track.

At some point in the overdub or mixing sessions I inadvertently dropped a stereo pair of drum tracks into record, effectively erasing the master drum track for a second or two. Fortunately, it must have been the overhead mics in a quiet period between cymbal crashes; nobody noticed and I never said anything. This was a relief, as during my first album sessions (Climax Chicago's Tightly Knit, recorded in 1971, Chris Thomas producing) I had managed to lose an entire performance. A complete list of my studio gaffes will no doubt appear in my autobiography.

Though unorchestrated and rather spare by contrast with Grand Hotel and Edmonton, Exotic Birds & Fruit is a meticulously-produced album. I think that, after the inevitable backlash at what some perceived as the extravagant production values of Grand Hotel, both Chris Thomas and the band were determined to make as unfussy and straight-ahead a rock album as possible. I think the artistic intent, whether or not it was ever verbalized, was to make a dense and detailed record that supported and enhanced the mood of the songs, but without drawing attention to the production. Chris Thomas was by now a very experienced producer who had, with Badfinger, Roxy Music, John Cale and others, explored most of the possibilities of reverb, double-tracking, editing, compression, and so on. The task that he and the band set themselves was to achieve a level of sonic excellence and musical interest that compared with previous triumphs like A Salty Dog and Grand Hotel without any of the necessary artifice becoming apparent.

One problem with pop records (as opposed to classical and jazz records) is that the form demands that they "build" from beginning to end - one stunning example is Phil Spector's River Deep, Mountain High - and one way of building a track is to keep adding instruments or voices as the song goes on. Hence all the tambourines, backing vocals, organ parts, triple-tracked guitars, etc., that show up on the closing choruses and fade of almost every pre-punk, "classic rock" record. But with tracks as long as As Strong As Samson and The Idol, there was obviously a danger in throwing in the extra ear-candy too early – anything added after the second verse would have to remain in the mix until the end of the song, which would still be another five minutes away.

The Beatles had attacked this problem in their own way with I Want You (She's So Heavy) on Abbey Road. Their intention had been to make a track that was really "heavy," at once a recognition that rock music had become a much denser form (eg Summertime Blues by Blue Cheer, You Shook Me by the Jeff Beck Group) and, at the same time sending the message that The Beatles, yes those once-lovable mop-tops, could rock harder than anyone. I Want You (She's So Heavy) builds and builds and builds and builds - and stops, probably because a fade would have been anticlimactic. Unfortunately, because of the limited dynamic range of the LP and the parameters of disc technology, the only people who really heard the track the way it was supposed to be were the band and engineers in the studio - the record didn't quite cut it, so to speak.

The Idol is comparable, in its production, to I Want You (She's So Heavy). It just gets heavier and heavier and heavier, though I can't remember what instruments were added as the song progressed, if any. But I know that the intention was to create a monster, a giant that came closer and more threatening with every step until the listener quailed before the looming threat. And I think that the band, Chris Thomas, and Punter largely achieved their aims.

Similarly, The Thin End of The Wedge was intended to be sonically unnerving. The relatively barren and unfurnished soundscape was carefully constructed to create dissonance and discomfort. I think someone (me?) might have suggested a Theremin overdub, or even clanking chains, but wiser heads prevailed.

|

Gary captioned this photo "Thanks Chris for Wedge 'n

all The writing instrument is a white Chinagraph pencil, commonly used to mark cue and edit points on the back of the tape. Photography:

Roberta Holyoak : |

|

Other tracks were more conventional. Butterfly Boys seemed to be descended from Simple Sister and Bringing Home the Bacon and may also have featured tape-echo on the kick drum, one of the many aural details that makes the Thomas-produced Procol records such a treat for sophisticated listeners. The lyrics, of course, are a barely veiled attack on Chrysalis principals Terry Ellis and Chris Wright.

Fresh Fruit obviously features marimbas or something similar, played by Gary or possibly BJ, or even both. There are percussion overdubs throughout the album, including my favorite percussion instrument, the "ass's jawbone," a sort of rattle that Roxy Music also used to some effect on one or two of their more theatrical numbers.

Mick Grabham was a real asset. Besides being a strong and stylish player, he was interested in the possibilities of multitracking (see here) and was happy to create multi-tracked beds of guitar which would often wind up fairly far back in the mix - not the kind of sonic filigree work that Robin would have readily agreed to, I think. As others have probably noted, playing lead guitar in a two-keyboard band which also features as powerful and active a drummer as BJ cannot be easy, and I think Mick sometimes felt that he had to fight for the spotlight, at least musically. But, despite his sometimes rather gruff and edgy demeanor, I think he was (and probably still is) a basically sweet character and a thoughtful and sensitive musician. I think he enjoyed the challenges of recording with Procol, at once subsuming his own agenda to the band's, yet still making a distinctive mark on the product.

That's Mick's voice at the beginning of the record, a tribute to the technically-challenged MCs who would introduce dance bands in the Northern clubs where he first started playing professionally. "Tommy" is Chris Thomas, though I don't think anyone but Mick and Gary called him that, and only rarely. Something else I remember about Mick is that, having tracked a solo in the studio, he would come into the control room and complain that his recorded sound lacked the "balls" that he felt he was producing in the studio. The band member who didn't like the recorded sound of his instrument was a staple of studio life - drummers were invariably disappointed when they came in the control room for the first playback - so it was some time before Chris Thomas investigated the complaint. As it turned out, Mick's level through his amp in the studio was such that any comparison was almost meaningless, but it also came out that Mick had apparently developed a visceral attachment to the ground-shaking abilities of his amp setup – his impossibly heavy Wallace 4x12 cabinet would literally make the floor vibrate – and thus could never really be satisfied by the recorded representation.

The mixing sessions were long and arduous, especially for the longer tracks, which required close attention to multiple cues as additional instruments came in (to minimize tape hiss, "empty" tracks were kept switched off until needed), and usually involved fairly complex reverb setups. AIR had four or five EMT plates (big metal sheets suspended in a box, not unlike legit theatre's thunder sheets) and one or two acoustic echo chambers. It was also common to have one or two 2-track machines running for tape echo or pre-echo delay, so the tape-op would have to rewind and cue as many as four machines before every mix pass. (In order to reduce tape hiss, even in the echo sends, Punter arranged to have the echo machines run through Dolby noise reduction modules, a testament both to his thoroughness and to the equipment resources at AIR.) Though the techniques used in the recording and mix were the same as for Broken Barricades and Grand Hotel, Thomas and Punter had become both more ambitious and more sophisticated. And though the overall production theme of the album was one of restraint - little orchestration and no choirs, no sound effects, no Moogs - the result was a highly-detailed and evocative soundscape which, I think, accurately reflected the mood of the songs and the character of the band. Unfortunately, though the single got some radio play, Procol were not attracting any new fans at that point in their career and it was the last album they recorded with Chris Thomas (though they did return to AIR with Lieber and Stoller).

It was also my last album session as a staff studio engineer. I had probably made the right choice in leaving AIR to go on the road with Pink Floyd (what today we would call a "no brainer"), but when I got tired of the psychological rigors of touring (the physical strain was much more manageable) I belatedly realized that my road experience counted for nothing in the studio world. Though AIR had taken me back on staff, I was now lower on the totem pole than when I had left, and would have to wait for young engineers like Steve Nye (who had previously tape op'ed for me) and Peter Henderson to move on before I would get much of a chance to engineer at AIR. So I regularly scanned the "opportunities" section of Melody Maker - that's how I landed the Jethro Tull gig - and noticed that critics' darlings Roxy Music were getting review after review for their live show that could best be summarized "looked fabulous - sounded awful." So I pitched myself to EG Management and got the job in February 1974. By the time I mixed Procol Harum on 4 July 1976 at York I was working more-or-less regularly as a live sound engineer and found studio work boring and repetitive.

But I always had a good time in the studio with Procol.

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |