Procol HarumBeyond |

|

|

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |

|

|

Authors: Brooker / Reid |

Read the words |

|

|

Performed: toured in Europe and UK |

Cover-versions: none |

|

The Worm and the Tree is considered by some fans to be the albatross round Procol Harum's neck, the nail in the coffin of the 'Something Tragic' album. But musically it is a very ambitious and varied suite of programmatic music, skilfully interweaving memorable themes and making use of leitmotiv: it features some of Gary Brooker's most sumptuous and sustained orchestration, if perhaps also his most conventional work. The circumstances of its recording have been widely, if contradictorily, commented upon: Mick Grabham said (Déjà Vu, 1977) 'We did virtually the whole of The Worm & The Tree in one day, it was like a magical day recording it from our point of view' yet in a Danish interview (2 February 1984) Keith Reid explained that 'We ended up doing it out of desperation ...'

In Zigzag (April 1977) Reid said that he '... wanted the storyline to be very simple so there would be lots of room for descriptive music ... if you take it for what it is, then I think that it's good.' Despite its musical elaborateness, Gary Brooker has said that '... we didn't even know we were going to do The Worm. We just played it one morning. Nobody knew it and it was very much improvised on the spot.' In the Danish interview Reid explained that The Worm and the Tree was '... an idea of mine that had been around for years ... people in the record company ... all had a concept of what a Procol Harum record was and they all liked having a long thing like In Held 'Twas In I.' It is probably in comparison with the variety and vibrant invention of that 1968 masterpiece that TWatT suffers most. Reid earlier told Zigzag that 'If you compare it to In Held then you're setting up a false standard, because it's nothing like that.'

Like In Held the original vinyl version was not banded, but three section names were specified on the record label, and the CD re-issue did divide the work into three tracks. For convenience we shall consider the music and words here under these section-names in what follows.

The entire suite did get quite a lot of airings in connection with the album. It was certainly played at the Pavillon de Paris (28 January 1977), and probably had its stage début at Ghent (Belgium) three days before. Then it stayed on the band's setlist for the Swiss and German parts of the Something Magic tour: at an early 1977 gig, presumably fearing that the piece would go down badly if it were not understood, Gary recited the story in German before the band performed it. Gary Brooker remembers that TWatT was never performed in Britain, but the ensuing English tour did feature the piece, which was often badly-received (notwithstanding, or perhaps because of, its accompanying slide show, which Mick Grabham judged '... diabolical ... just awful, awful ...' here) most notably at the Oxford Playhouse. It featured at relatively few gigs (eg Oxford, Liverpool, Manchester, London, Bristol), and it is not in the radio or TV shows of the time. TWatT did not make it across the water for the US leg of the promotional tour by then in any case Dee Murray had been recruited on bass and TWatT would have been a tall order to learn in a short time. It has not been performed since, with the exception of a fragment played, by GB at the piano, at the Barbican in December 1999 (hear it below). Part of the Enervation section, however, was recycled, post-modern style, in the unpublished Last Train to Niagara, a mammoth retrospect of Procol words and music that Procol Harum toured in 1993 (mp3 here).

The Palers' Band performed The Worm and the Tree to Procol Harum and fans on 20 August 2006 in Denmark: Click here for Gary Brooker's response the audio clip touches on the reasons for the suite's having been recorded.

Overview of the Suite

The text has quite a high quota of anachronisms (eg 'the tree be not dead') and redundancy (eg 'a small worm did go'), redolent of people's impressions of 'Ye Olde English' of Chaucer's time. This, along with the simplistic rhyming and metre, and the reiteration of lines from stanza to stanza, contributes to its kinder-fable character. When it was suggested to Reid that the piece might lend itself well to animation he agreed: 'Yeah ... were thinking about maybe a cartoon of some kind.' (Wax Paper, 25 February 1977). Chris Copping summed up its flavour when he said (here) that the Worm was 'special - sort of Tolkien-like'.

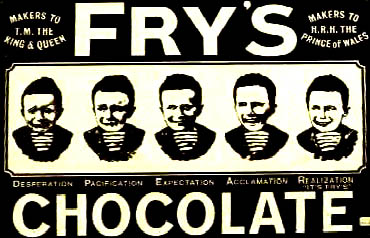

The section-names [Introduction-Menace-Occupation / Enervation-Expectancy-Battle / Regeneration-Epilogue] seem somewhat contrived, but it reminds a generation of British listeners of Fry's 'Five Boys' chocolate which was marketed in the 50s and 60s in a wrapper depicting a sequence of five facial expressions each named with an abstract noun ending in '-ation': Desperation, Pacification, Expectation, Acclamation, Realization it's Fry's! [The same advertisement may underlie the naming of The Cure's Five Imaginary Boys]. Incidentally, G de Givry's Witchcraft, Magic and Alchemy shows (p 368) in a seventeenth-century English tree-type diagram of the alchemical operation; up the 'trunk', in boxes in this order, come 'purgation / sublimation / calcination / exuberation / fixation / solution'. Various other accounts have 'separation / conjunction / distillation / assation / reverberation / dissolution / descension / coagulation'.

The decision to have Brooker recite in a somewhat astonished tone, rather than sing, adds to the impression of the work being for children, somewhat in the manner of Britten's Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra or Prokofiev's Peter and the Wolf, which latter Brooker contributed to in a 'rock' version hosted by Vivian Stanshall. The band was planning initially to import a thespian narrator, such as James Mason; Brooker claimed that he would have worked out how to sing it eventually: but he does have a penchant for recitation, previously exampled in Glimpses of Nirvana, Dead Man's Dream, even Thin End of the Wedge.

So what might it all mean? On a literal level, an ordinary (earth)worm would not attack a tree, nor might a worm grow from a tree (we do not seem to be dealing with woodworm here, as this worm doesn't change its form as it matures). So a metaphorical interpretation would seem to be invited. In a nutshell, the symbolic tradition is that tree stands for good, and worm for bad; certainly the Oxford Playhouse audience in 1977 responded to the piece with the pantomime-audience behaviour that suits a simple tale of good versus evil.

'Worm' is the old term for lowly creatures in general including snakes; it was originally spelt 'wurm' and is probably of Teutonic origin. ('Worm' and 'snake' are still interchangeable put-downs in conversation: 'you behaved just like a snake'). Folklore supplies heroes like St George, who defeated the dragon, or St Patrick, who cast the snakes out of Ireland: these feats have been explained in geomantic terms and have their equivalents in the lore of feng-shui. Lewis Carroll's Jabberwock, in the famous illustration by Sir John Tenniel, gives us forest, hacking sword, and a monster whose receding tail becomes ever more worm-like: this frightening, resonant image can surely be found deep in any literate British child's mind and its by no means the only indication we have that Reid knew his Carroll.

Edgar Allen Poe famously writes (in Ligeia, 1843) of the 'Conqueror Worm', which is 'a blood-red thing that writhes from out ![]() the scenic solitude', to devour the hero of 'the tragedy, Man'. This is the same creature that Hamlet so marvelled at ('Your worm is your only emperor for diet: we fat all creatures else to fat us, and we fat ourselves for maggots'! Act IV sc iii) which will, in the end, consume us all: Poe's piece has no tree-corrupting element, but much of its imagery (see here) resonates with other Reid words.

the scenic solitude', to devour the hero of 'the tragedy, Man'. This is the same creature that Hamlet so marvelled at ('Your worm is your only emperor for diet: we fat all creatures else to fat us, and we fat ourselves for maggots'! Act IV sc iii) which will, in the end, consume us all: Poe's piece has no tree-corrupting element, but much of its imagery (see here) resonates with other Reid words.

There are several other pieces of European folklore involving threatening worms, such as the tale of the Lambton Worm [from Mick Grabham's native North-East] which exists in this Reidly kind of verse form, and the legend retailed in Dracula author Bram Stoker's Lair of the White Worm [also a film by Ken Russell] in which an evil woman offers human sacrifices to a snake/worm deity. This would seem to be an obvious projection of phallic anxiety.

A more general fleshly guilt has been associated with a 'worm feeling': Max Weber, in The Protestant Ethic and the Sprit of Capitalism [p.131 Unwin books 1965 edition], is translated thus: '... it was possible for the Calvinistic idea of the depravity of the flesh, taken emotionally, for instance in the form of the so-called 'worm feeling', to lead to a deadening of enterprise in worldly activity ...' This tallies neatly with the withering of the 'great tree' in Reid's text.

Trees occur symbolically in various didactic texts: there is a stinking tree in Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress which needs to be cut down to let it grow afresh, and Reid's narrative likewise emphasises the terrible smell, poisoning the ground. Blake's A Poison Tree is another well-known application of this archetypal metaphor, where jealousy and guile poison a fruit-tree; it shares something of the faux-naïf style of Reid's text here; elsewhere in Blake's Songs of Experience we read of 'the invisible worm' that flies in the night and invades the sick rose. Blake's own illustrations to the text make clear the phallic symbolism.

Confucian writers, like Christians, have used tree stories to illustrate their wisdom, as may be seen in the following: 'When Tzu-ch'i of Nan-po was taking a stroll by the Hill of Shang he spotted a great tree that towered above all the rest. Its branches could shelter a thousand horses and its shade would easily cover them all. 'What kind of tree is this?' he thought, 'its timber must be quite extraordinary.' But when looking up he discovered that the higher branches were too gnarled to be used for floorboards or rafters. When looking down he noticed that the trunk was too soft and pitted to be used for coffins. He licked one of the leaves and it left a burning taste in his mouth. He sniffed the bark and the odour was enough to take away his appetite for three days. 'This wretched tree is completely useless,' he exclaimed, 'and this must be why it has grown so large! Aha! this is the exact kind of uselessness that the holy man puts to great use.' [Chuang Tu p.45 Two Suns Rising. Jonathan Silver].

However the principle 'snake' in Western culture is the serpent, Satan's guise as he introduced sin into the Garden of Eden in Genesis. Since the other key image in that myth is the Tree of Knowledge, we might expect this piece to present an allegory of quasi-Biblical temptation: however it seems to lack a symbol corresponding to the apple, although such a fruit would be the very part of any tree that could reasonably be invaded by worms, ending the regenerative cycle.

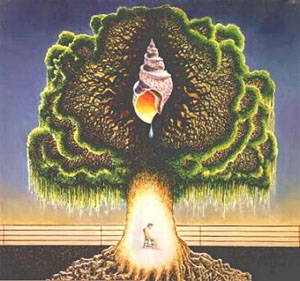

The Something Magic album artwork, by Bruce Meek, appears to respond quite literally to the imagery of this long track. The vignettes inside the gatefold use a children's picture-book style to illustrate the unfolding of the story, using a worm of improbable pythonic dimensions which enters the tree from without and is challenged by a particularly tiny 'young man' in European hunting costume of an indeterminate past era. However the large illustration (reversed left to right in the CD booklet) is at odds with these cameos: it shows no worm at all: instead the tree is occupied by an abandoned mollusc-shell, from which a single tear-drop is about to anoint a tiny, defeated-looking human figure [resembling the band's lyricist, some claim] who grips a wooden chair in suicidal posture. The symbolism is obscure at best, except for the empty musical stave behind, which surely symbolises a barrenness of invention while the 'great tree' is afflicted by this internal disorder. How ironic it is that, through the antagonism of the Albert Brothers to Procol's other new material, this fable about regeneration was in fact to provide the last recorded notes of the band's original career.

Introduction-Menace-Occupation

Introduction

The piano opens with what we might call the 'tree theme', a simple monophonic motif that seems to be in G minor until its final, sour note. The last three notes of this motif, captured by the sustain pedal, replay the highly characteristic chord that starts A Salty Dog, pretty well unknown elsewhere in rock, but also featured in Holding On; it's very much a Brooker signature. The same might be claimed for the right hand expansion and contraction of the chords that follows, perhaps heard at its most conspicuous at the start of Simple Sister. Here, however, we are in A flat and F minor, shifting from 7/4 to a more familiar 4/4. At over a minute, this is the longest unaccompanied piano sequence in the Procol repertoire.

Bass guitar, high strings and kettle drums take up the placid 'tree theme', with tom-tom or timpani punctuation, then it 'grows' with eerie synth and faux Hammond, perhaps also some high guitar in the style Mick Grabham perfected in the Albinoni / Blue Danube recordings. Dark colours are supplied by horns, Leslie 'Hammond', and countered by some glittering concert harp.

Menace

This episode presumably starts at about 2.40, when Brooker's vocal comes in. The 'tree theme' has now grown an extra phrase, and it's followed by what we might call the 'worm theme', a little six-note motif that we first encounter in an alarming two-apart 5/8 fugue in E flat minor (by no means the sort of thing a pianist can rattle off at a gig without a lot of concentration!). This 'worm' fugue is soon surrounded by the 'tree theme' in A flat minor and G flat minor (the juxtaposition of diatonically unrelated minor chords is another recurring device in the piece). Winds and pizzicato strings dramatise this opposition. The 'worm' theme on the piano adapts to the 'tree' key of the ensemble, and the 'tree' carries it into another, through a kaleidoscope of keys in fact. The 'worm' then goes on climbing, growing, and an orchestral tutti ends the sequence in the complacent expansiveness of an E major chord.

105 seconds of music are missing from the Salvo remastered reissue CD that includes this suite (2009). 'Menace' in Part One lacks the section that (on the vinyl release) comes after the spoken 'the tree shrank away'. The Salvo CD doesn't include the attractive 5/8 Eb minor canonical two-part invention on the piano, with its orchestral accretions, nor the following monologue from 'worm was so greedy' through to '... terrible fate lay in store for the tree.'

Occupation

At 4.32 the 'tree' theme returns, the 'worm' theme reduced to one phrase in the left hand of the piano (darkly heard under 'what terrible fate lay in store'). But then comes a lovely largo in pure Baroque Procol tradition, most reminiscent perhaps of Matthew Fisher's Separation in its relentless geometrical unfolding. This is a 4/4 version of the sinuous 'worm' fugue, now in E minor, blending band and orchestra delightfully. Plaintive woodwinds elaborate the counterpoint, and Solley is at his most Fisheresque. BJ's drumming is distinguished by a characteristic triplet fill. One wonders what melody Gary could have found to sing over this rich backdrop? The texture is once more darkened by guitar, and the movement climaxes with an orchestral reiteration of the 7/4 motif from the introduction, this time in E major. We end on a darkly-sustained A flat minor chord.

Enervation-Expectancy-Battle

Enervation

To enervate something is to deprive it of strength or spirit, not an idea that readily chimes with the mood of this new section's music, one of heroic expectation. The orchestra has dropped out, leaving the band to canter, crisply driven by BJ's drums, through a restless D minor chord sequence, peppered with the suite's first added sevenths and sixths, yet retaining the side-slipping chord-changes from before. This 'young man' theme aptly enough 'rides' on a pedal D; its initial chords would fall easily under the hand of a three-string guitarist, and it's tempting to imagine them being discovered first on that instrument.

The seeming inevitability of the sequence as it breaks away from the pedal note with a descending churchy bassline is compromised by unexpected, further semitonal descents (foreign to the otherwise diatonic development) to a cadence in C minor, from which Brooker returns to D minor with a syncopated kick from the Simple Sister song-bag. Solley's break shows him to be a very fluent soloist there's a hint of the displaced accents that so distinguish the Fisher organ solo in Shine on Brightly the twin synths fade in and out of the stereo in a way that couldnt be achieved in performance. Unusually literal even for this album is the hunting-horn call, inserted by the synthesiser when the vocal, at 1.30, introduces the 'young man'.

His realization of 'the right cure' is signalled by a brief, brassy D major march using horn-wise writing: we hear an echo of Without a Doubt in the way the seventh in the bass of one chord resolves upwards into the fifth of the next. This brief tune modulates quickly into B major, but baldly returns to D major for its second statement: this surprises the ear, but is not entirely satisfying ... and the fade is very long.

Expectancy 2.54

We now hear a pounding 'chopping rhythm' from the piano, whose oompah chords imitate the vigour of the young man's exertions. The chordal ostinato climbs in intervals of a minor third (like the bassline of All This and More), first alternating A minor 7 with F# minor, then C minor 7 with A minor, then E flat minor 7 with C minor and F# minor 7 with E flat minor. Drums and bass join in, building tension as the tonality shifts; we will hear these unusual, shifting minors again at the end of the work in the orchestra ... which now bursts back in for four grandiose, worm-hacking chords.

Battle 3.52

Grabham's magnificent guitar solo explodes, as if after an eternity of pent-up anticipation. 'It took a while to get the big sound on that,' Grabham recalls. It was done '

using a hired Marshall stack, turned up as loud as it would go, with no headphones; they turned the fold-back in the studio up and I was listening to speakers all the time.' It is easy to see why the band were so pleased with the piece, containing the most stirring playing they'd produced in several albums. 'Good set of chords, ultra-dramatic!' Gary Brooker recalled, in conversation with BtP. They are chiefly the 'young man' chords, the ostinato amplified by grand orchestration, with a measure or two of the 'chopping theme' thrown in for its pictorial quality. The tension of the 'young man' chords begins to dissipate, now that there's movement in the bass, but overblown horns build up excitement, underlined by tom-tom triplets matching the guitar's. At the end we hear the severed worm-fragments pile up, while the strings mimic the vorpal flashing of the blade, and the worm's last howl (one note dropped in from another take with the help of Stephen Stills, according to Mick) fades slowly on an unexpected cadence in G minor.

Regeneration-Epilogue

Regeneration

This solo piano waltz in G, with its exaggerated rubato, is one part of the suite that really does sound as though it is the accompaniment to a song we never hear; Gary Brooker liked it enough to resurrect a bit, supposedly at his wife's request, at the London Barbican in 1999 (mp3 here). On the album it is richly recorded, with a full range of overtones from the piano: the elaboration of the second chord is reminiscent of Without a Doubt again. The transparent texture does successfully suggest the clearing of the rain-clouds, and when harp, strings and woodwinds come in at 1.34, a pastoral effect is achieved, despite BJ's military snare rolls. Up to a point you can sing the words of this section to this melody, though it's hard to imagine the singer who could make anything of the rather routine upward major scale at the end, nor hold the last note of the plagal cadence, the 'amen' sound that perhaps fits a sense that 'it is finished'.

Epilogue

The final movement starts at about 2.49 in the last track, in the same key as the preceding section: it's a solemn march in four-square Handelian style, with the bass line a crucial element of the composition. There are shades of Grand Finale here until the music gives way to the patent 'slipping minors' style of the 'chopping theme'; then we get an essentially formulaic upward scale that soars into the final tutti, the libretto's spreading new life being evoked with seething synthesiser work. The piano belts out a generic fanfare-like rhythm, which is also heard in Wreck of the Hesperus and Grand Hotel; the strings saw away, as if for the Arrival of the Queen of Sheba, as the 'chopping theme' is heard for the last time and the ensemble slows down for the sudden, final chords of the suite. But it's not the end just as we get up to turn the record over again, a tentative rebirth as the 'tree' theme puts forth a tiny shoot

Gary said in a BtP interview that he could never figure out 'if the music [of TWatT'] states what has just happened, or what is just about to happen.' Similarly one might wonder whether the suite predicted, or actually caused, the demise of the 'Old Testament' band? Brooker, interviewed on Dutch Radio (TROS Poster, 25 October 1979) commented in typical fashion: 'As with a lot of things that we always did, we're much more prophetic about ourselves ... if we said something, even if it hadn't happened, it would turn out to be ... when we finished recording it we went on for another two or three months ... and then we sort of stopped.'

As must this disquisition.

|

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |