'How to separate the fiction,

contradiction, from the fact'

A substantial BtP exclusive with Keith Reid,

about his 2018 solo album, In My Head

Keith Reid meets me, at his

own suggestion, on the steps of the Victoria

and Albert Museum in Kensington. Jestingly I inquire if this famous edifice is ‘his local’,

his London residence being so close. ‘It’s the old cliché,’ he replies. ‘Live so

close, yet I haven’t been here in years.’ As we meander through the Chinese

Gallery – each assuming the other knows the way to the Madjeski Courtyard and

its open-air café – he adds that it’s no different the other side of the

Atlantic … you can keep a place in Tribeca, but you haven’t necessarily climbed

the Statue of Liberty.

Keith is no stranger, however, to

nearby Hyde Park,

where, he tells me, he belonged for a year to the

Serpentine Swimming Club, and

swam there daily at 7 am. ‘In winter you can’t stay in for long, of course, but

the blood rushes out to your skin …’. Sounds exhilarating, I say, but is it good

for you? With a gesture straight out of Waiting for Godot he indicates

his own person, inviting me to judge for myself.

Keith is no stranger, however, to

nearby Hyde Park,

where, he tells me, he belonged for a year to the

Serpentine Swimming Club, and

swam there daily at 7 am. ‘In winter you can’t stay in for long, of course, but

the blood rushes out to your skin …’. Sounds exhilarating, I say, but is it good

for you? With a gesture straight out of Waiting for Godot he indicates

his own person, inviting me to judge for myself.

Freshly turned 72, Keith remains

enviably lean and nimble … alarmingly so, in fact, when he dodges into traffic

to cross the Cromwell Road as we part a couple of hours later. Readers may feel

that he dodges pretty nimbly around one or two of my questions as well; but our

two hours’ conversation feel open, thoughtful, intriguing … and always affable.

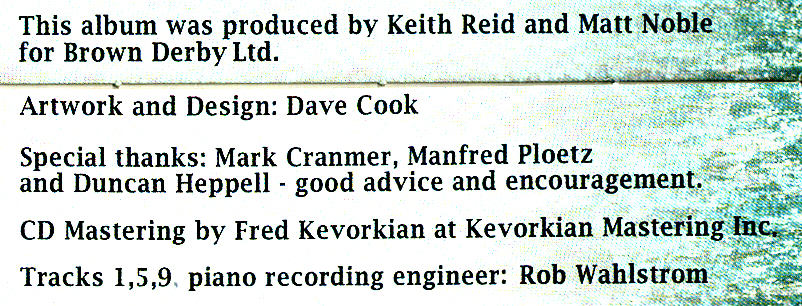

Our topic – pretty well

exclusively – is his new album, In My Head,

due for UK release on 7 December, and a fortnight later over in America: buy or

pre-order it

from Amazon.co.uk or

from Amazon.com. I’ve been listening to it for a week – in a nutshell, it's surprising, engaging and thought-provoking ... a

must-have – and quickly

find out that I’m the first person he’s talked to about it. He’s interested, and

amused, to know how it’s struck me.

Our topic – pretty well

exclusively – is his new album, In My Head,

due for UK release on 7 December, and a fortnight later over in America: buy or

pre-order it

from Amazon.co.uk or

from Amazon.com. I’ve been listening to it for a week – in a nutshell, it's surprising, engaging and thought-provoking ... a

must-have – and quickly

find out that I’m the first person he’s talked to about it. He’s interested, and

amused, to know how it’s struck me.

Like Keith’s previous solo

offering, 2008’s The Common Thread, In My

Head features music by various composers sung by various artists, and

consequently offers a less cohesive listening experience than the typical Procol Harum record of yore …

arguably the only similarity is that in

both cases all the words were written by Keith.

‘Do you think of the new

album as a compilation?’ I ask. He weighs his answer carefully.

KR

Not a compilation, no, it’s an accumulation, because I write songs all the time.

It’s a question of accumulating songs until you have enough to make a record.

I remind him that,

in 2008, he declared he had 'plenty of

other items that might have made the cut' but, as he then observed, '55 minutes

[thirteen tracks] seems plenty: sometimes too much is worse than not enough.'

BtP

I notice the new collection [which comprises ten songs over about forty minutes]

has been ten years in the pipeline ...

Well, goes to show, time flies!

Laughter.

Ten years, what’s wrong with that?

More laughter.

Well I haven’t been working on it for ten years. These songs have been written

over the past few years, some more recently than others. But I got down to

serious recording in … let’s think … the serious commencement of this record,

when I got started in earnest, I can date clearly, because I was working in

Sweden and I was driving to the airport when we heard on the radio that same

weekend

Julian Assange took refuge in the Ecuadorian

embassy.

Was that cause and effect?

Yes

– laughter –

he needed to get out of my way!

Of Keith’s 2008 singers – Steve

Booker (2 songs), Chaz Jankel (1), Southside Johnny (2), Terry Reid (1), Michael Saxell

(1),

Bernie Shanahan (2), Chris Thompson (2) and John Waite (2) – only Waite and Booker

are involved again in 2018; and of the fourteen 2008 composers – Steve Booker*,

John DeNicola, Barry Goldberg, Jeff Golub, Chaz Jankel, Anthony Krizan*, John

Lyon, Matt Noble*, Andy Qunta, Maggie Ryder, Michael Saxell, Mark Taylor, Chris

Thompson, John Waite* – again only a small minority (marked with asterisks) are featured in 2018.

You didn’t revisit many of the

collaborators from the first record?

That wasn’t deliberate, it was just the way

it worked out.

The John Waite and Steve Booker

songs on In My Head, are they coeval with those composers’ contributions

to The Common Thread?

I don’t think so.

One strong point of continuity is

the record label, Rockville. I ask Keith why his music is being published by a

small company in faraway

Bavaria.

I just really like the guy who

runs the label. Manfred, who did the last record: he wanted to do this one, at

the same time as I wanted to do something …

When Manfred Plötz

was asked, in a recent interview, how he would describe Keith's new collection,

his response included 'In My

Head is a wonderful collection of soulful songs, featuring six different

singers. But it's not only the music. It's also Keith's extraordinary talent for

writing lyrics. Keith Reid is a wonderful poet, and he's a unique phenomenon in

music history: being an essential part of a band (Procol Harum), but not sharing

[the] stage.' Plötz

himself plays in the band

Pavlov's Dog, whose new album – resonantly entitled Prodigal Dreamer – is

released the same day as Keith's.

How did you two become acquainted?

I think

somebody introduced me to him but … I really can’t remember …

Reid's memorial drive appears to

stall, and he laughs. We both know there will be quite a lot of answers of this

kind. The Assange/Ecuadorian Embassy episode was August 2012, so I realise I’m not

necessarily asking Keith about recent history. I turn to specifics of the

record.

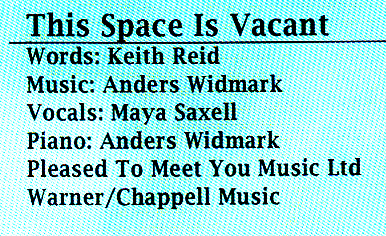

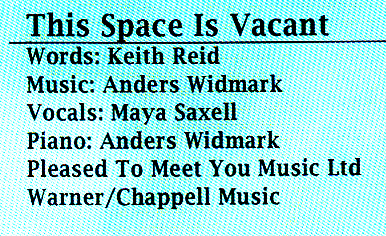

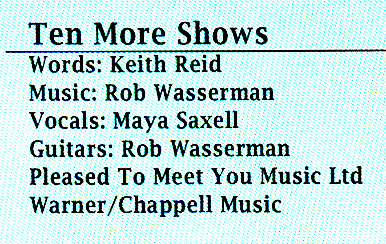

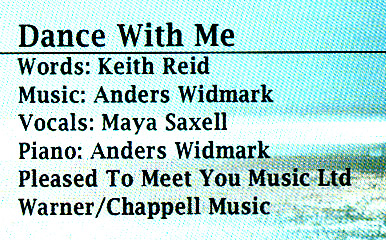

The

first track on the album is a huge surprise, I tell him. This Space is

Vacant (4.10) – intimately sung by Maya Saxell, and accompanied

exquisitely at the piano by Anders Widmark, a big name in Swedish jazz – marks a

major departure from the tone and density of The Common Thread. I ask if

Maya is related to 2008 Reid collaborator Michael Saxell, the Grammy-award

winning Swedish hit-meister. The answer comes back, immediate, fluent.

The

first track on the album is a huge surprise, I tell him. This Space is

Vacant (4.10) – intimately sung by Maya Saxell, and accompanied

exquisitely at the piano by Anders Widmark, a big name in Swedish jazz – marks a

major departure from the tone and density of The Common Thread. I ask if

Maya is related to 2008 Reid collaborator Michael Saxell, the Grammy-award

winning Swedish hit-meister. The answer comes back, immediate, fluent.

Maya, yes,

she’s the daughter of Michael. He played me a tape of her doing a Bruce

Springsteen song, and I really liked the way she did it. And I filed her away in

my memory: ‘I really like that girl’s voice’. And later on, when I was looking

for the right singers for these particular songs, I thought, 'Let’s see how she

sounds.'

This Space is Vacant

is a song about the narrator’s interactions with a homeless person whom he’s

wont to pass in the street, but who’s suddenly absent. The first verse uses deft

and ingenious half-rhymes to set up the scene:

I used to see him every day, sleeping on the pavement

But lately when I pass that way I see

his space is vacant

‘Spare change,’ he used to say, ‘I’m

not your entertainment’

The straightforward good cheer of

the indigent – who asks ‘why are you so sad?’ – is contrasted with the

ambivalent thinking of the walker, who sometimes, like a bad Samaritan, crosses

the street to avoid him; and we gradually learn that he himself has no

particular place to go; the parallel is drawn and we start to wonder whether

he’s a candidate for the empty place on the pavement. I’m puzzled, perhaps

haunted … by a ‘disconnect’ between this tale of two directionless men and the

womanly voice that sings it. Close-miked, sultry Maya’s style would suit a

bedroom confessional, and chimes askance with Reid’s unflinching interrogation

of his imperfect relationship with the homeless, ultimately absent

man. The interiority of the performance makes a strong impression … yet the

story is the tale of a street.

What are we to make of this ambiguous

narrator?

I don’t think

of him quite the way you do …

But isn’t that a giveaway? We’re saying

‘him’ not ‘her’. You’ve given the lyric to a woman.

Particularly

with these Maya tracks, the thing I really liked about her is that she really

inhabits the songs, she’s living it. She does in my opinion what a really good

singer should do, sound as though she means it, and she’s experienced it. And

basically, that’s what I’m looking for in deciding who’s right for different

songs: people who will really inhabit them.

In fact Maya inhabits forty

percent of the new album and is in every way a standout. I wonder if Keith had

written with her in mind.

No, I wrote

those songs before I’d ever met her. All the songs on the record … they’re all

about me in some way – and that’s partly why I called it In My Head – and the

singers are just … I’m using different people to represent, no, to voice me. But

that’s always been the case; that was the case with Procol Harum songs too.

I suggest that in the Procol days

fans felt they were effectively hearing the Reid voice, even though it was

almost always Gary Brooker singing the words. Though Gary sang soulfully, it was

never histrionic; he was never acting a part, and seemed a relatively

transparent vehicle for the lyricist’s insights and imagery. But now, given the

profusion of varied characters voicing Keith’s thoughts on these two

solo records, it’s hard not to think in terms of personalities and how these

match – or colour – the material. Maya Saxell, the only woman on the team, is a

radical departure and brings something really new to the Reid world: one can't

help noticing that, if her name were an anagram, it would be only one

letter adrift from ‘I am all sexy’.

Is it?

Laughs.

I’d

better not tell her that. Look, initially, I just did the piano, and actually at

that stage I hadn’t made a decision what I was going to add to the tunes apart

from getting the right person to sing it.

Keith tells me that composer

Anders Widmark, in Sweden, had not only played some brilliant piano –

conspicuously, his chord voicings vary (sometimes fleetingly) to reinforce the

emotion of the lyric – but had provided a guide vocal.

You were there for his piano recording?

I was

responsible for the piano recording! He’s a fabulous piano-player.

And how do you know Anders?

As with

Michael Saxell … these things recede in my mind, but I must have met him through

the famous Ingmar Bergman [story here!]

How often one says that!

(Laughter).

So you went to Sweden and did stuff with

Maya?

I went to

Sweden – to Gotland, to be precise – to record the tracks with Anders, who wrote

the music for those three songs. Maya lives in Vancouver.

You mean they’re not playing together in

real life?

I’ve given

something away there. You see this is the wizardry … when people say, 'What do

you do in a recording studio?' ...

Is there anything that’s ever done in your

absence?

I produced it

all. Hands on with everything, all over the place. The record was made in

Sweden, America, and Canada. Vancouver’s in Canada, isn’t it?

So you were in Vancouver?

No, that’s

where Maya is; I sent the tunes to her, and then we talked about it a lot, and

she sent her parts over.

Amazing. It really sounds like a man and a

woman playing together, when you've just set up a mic and happened to get

one brilliant take. Whereas there are other tunes in this accumulation that positively invite us

to imagine the multi-tracking involved. I’m almost shocked to learn that Maya

was not curled on a cushion adjoining the piano stool, but recorded her part far away in

space and time, and then simply dropped it into Anders Widmark's recording.

There were

some technical difficulties which had to be sorted out, so it wasn’t quite as

simple as that. But it is totally organic. We married the two elements together

with Matt Noble – he’s my trusty compatriot in that respect. Back in the day a

producer was always in the room at the time, but I don’t think that’s the case

these days.

Can you remember why

you made this one the lead track?

It kind of

set the tone for the album, when the Maya tracks were done, and I thought

‘that’s the kind of record I’d like.'

You didn’t think of doing a whole album in

that way?

Pause.

Maybe one of

these days.

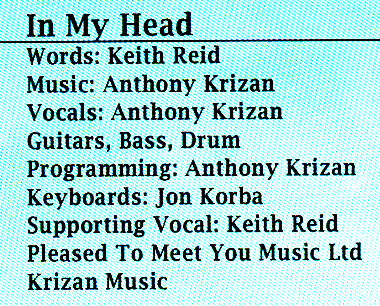

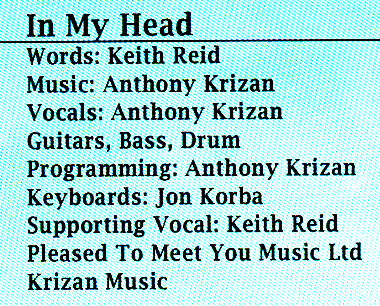

Needless

to say the second track, which gives its name to the whole collection, presents

an enormous contrast. Prominent lead guitar (textural, not really melodic, and

sometimes recorded backwards), groovy beats, and an assertively mobile bass line are provided by The Spin

Doctors’ sometime guitarist Anthony Krizan, who also sings.

Needless

to say the second track, which gives its name to the whole collection, presents

an enormous contrast. Prominent lead guitar (textural, not really melodic, and

sometimes recorded backwards), groovy beats, and an assertively mobile bass line are provided by The Spin

Doctors’ sometime guitarist Anthony Krizan, who also sings.

Anthony? I met him through

Frankie LaRocca. He’s a

[New] Jersey guy, and I met him

when I did the overdubs on Thieves’ Road at his studio in Jersey. That’s

where I did In My Head, in his studio.

The highly original lyric presents two voices

debating the relative merits of original versions and covers, in terms both of

songs and of films. One voice puts the younger point of view and the other

responds with self-deprecating humour recalling Procol’s Yours if You Want Me.

I remark that the energy and weird vocal style of In My Head

(3.57) make it a second standout in a row, and remind me of

The Only

Monkey, the most aggressive and challenging song from the previous album.

I

do like that a lot. I’m going to redo that tune one of these days.

Why’s that?

Do it with

… (he ruminates)

Orchestra and chorus?

(laughter)

Some people

thought it was just comic. And it was intended to be humorous, but not comic, I

don’t think.

Chuckles.

But anyway I will redo that song at some point.

Whereas

The Only

Monkey was

bleakly misanthropic (its bluntness underlined by some brutal key changes in

Chaz Jankel’s instrumental track) In My Head is genuinely funny.

In my head I’m Motörhead, in my head I’m

Lemmy

In her head I’m halfway dead, old and

weird and smelly.

In my head I’m Motörhead,

dangerous and crazy

In her head I’m Father Ted, old and

weird and lazy.

At least, it starts out funny,

though the tone shifts when the ‘old and weird and lazy’ voice declares

‘Now it’s all a

piece of shit and no-one gives a fuck’

Yes, but the

whole song is supposed to be like that, about remaking things.

I’ve never heard that song before, I think this record’s cool

You always say the old one’s best,

you’re just a sad old fool.

Do you really think that old versions are

always better, and remakes always dodgy?

Yes,

absolutely.

You’re not just adopting a grumpy old man

position?

It’s a wry

commentary! But yes, the music was always better then, but it isn’t worse now,

because there’s lots of great music coming out now.

The two generations in that song are

characterised by different voices. Who are the two vocalists?

It’s all

Anthony, all Anthony Krizan.

But I notice there’s a ‘Support Vocal’

credit for ‘Keith Reid’.

It’s in the

chorus, ‘In my head I’m

Motörhead’.

I’m there. I’m in there.

Singing?

[The chorus is a primitive riff, delivered in a

distorted, manic holler]

I don’t think

I’d call it singing. Anyway, through the magic of the recording medium, I’m in

there.

I remind Keith of his previous

Hitchcockian micro-role on The Common

Thread … another parallel with The Only

Monkey, in fact.

I’d forgotten

about that.

But whereas the

Monkey song

is a critique of all humanity, this one is more about the foibles of one character, and it’s more

culturally specific, or even limited. I ask if

Father Ted is known

in the States?

A good

question: we’ll find that out. They get BBC TV over there, they have comedy

channels over there, and considering there are such a lot of Irish people in

America … put it like this: (a) I don’t know, and (b) I imagine so.

And (c) it’s not even the Father Ted

character himself who’s ‘old and weird and lazy’ ... isn't that the alcoholic,

Father Jack?

Is that

right?

Uproarious laughter.

Arguably of course this Father

Ted error, from the narrator, could be taken as an additional affirmation of

his out-of-touchness with relatively-recent mass entertainment. But before I can

come out with that, Keith plays his own get-out-of-jail card.

Well anyway,

it’s Art. I’m allowed to …

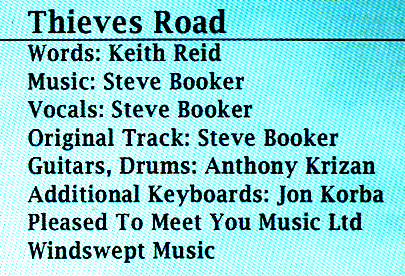

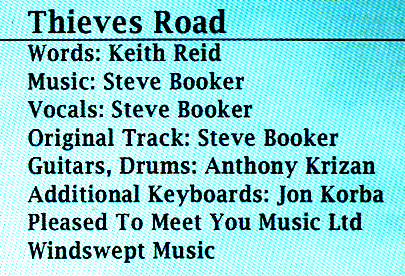

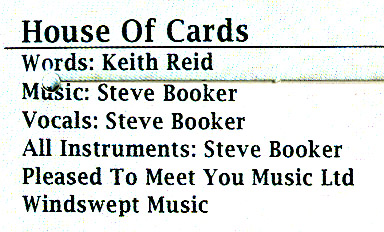

Thieves’

Road (4.45) doesn’t concern itself with jail, nor the courts, but offers

a kind of admonition to an unnamed ‘you’ who ‘… rode your winning streak down

where the crossroads meet’. The language remains somewhat indeterminate, and,

like the music, doesn’t offer too many surprises. Sprightly acoustic rhythm

guitar, solid four-to-the bar bass, rhythm shakers, piano and languid, slightly-distant lead guitar offer a pleasing,

if unvarying, listening experience. By

comparison with the foregoing numbers, this Booker/Reid song seems a more

mainstream piece of work.

Thieves’

Road (4.45) doesn’t concern itself with jail, nor the courts, but offers

a kind of admonition to an unnamed ‘you’ who ‘… rode your winning streak down

where the crossroads meet’. The language remains somewhat indeterminate, and,

like the music, doesn’t offer too many surprises. Sprightly acoustic rhythm

guitar, solid four-to-the bar bass, rhythm shakers, piano and languid, slightly-distant lead guitar offer a pleasing,

if unvarying, listening experience. By

comparison with the foregoing numbers, this Booker/Reid song seems a more

mainstream piece of work.

Did all these songs start with the words?

Yes.

Probably. … probably. I’d have to go through it in my head, but probably.

You made a precious vow

but you broke it anyhow

You’re out of favours

You hid your smoking gun

out where the buffalo run

you’re no angel

Thieves’ Road struck me as a

possible exception … it’s quite unusual to have six lines before the chorus, and

Steve Booker plays around with the vocal rhythms, to fit them into

the song meter. I wonder if there was a rhythm track first.

I think he

had a feel first: I think he told me he’d got something, and then I started

writing.

So Steve Booker, he’s writing, singing,

multi-tracking. It’s nice that the who-did-whats here are more complete than on

the previous record.

Yes,

Steve did the

basic tracks, but then we added to them: I did that in New York, in Jersey.

Are there any unlisted musicians?

I’ve tried to

be pretty exact. Jon Korba played the mellotron on Thieves’ Road, and

piano.

Is Korba another Noble associate?

No, he’s with

Hall and Oates sometimes, I think. He’s a Jersey guy. They all know each other.

Do you work from a list of singers, mixing

and matching, mating the right voice with the right song?

It works in

different ways. With In My Head, for instance, it hadn’t particularly

been my intention for Anthony Krizan to sing it, but when we were putting the

tune together I thought he sounded really good on it, and I didn’t feel there

was any reason for me to get anyone else to sing it.

I suppose the modern-day song-writing

process almost always involves a recording-machine running, so the songwriter is effectively

making a demo on the fly?

Yes, and

quite often the composer will do a guide vocal, even if you get together with

the intention of writing a song for a particular artist.

Is that what happened with You’re the

Voice? You released (composer) Chris Thompson’s early version on The

Common Thread, but of course

the huge hit came with

John Farnham’s voice.

You’re the

Voice was for Chris, and Chris was going to do it, and I know he kicks

himself to this day, although it wasn’t his fault; that song was for an album

that he was doing but the producers told him they didn’t think it was a very

commercial song, and left it off the record.

As almost happened with Over the Rainbow and

the Wizard of Oz producers.

I didn’t know

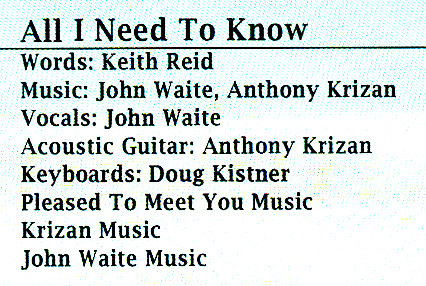

that. Another example, All I Need to Know, the one that John Waite’s

singing, I wrote it with him and Anthony Krizan. And you know, if you’re writing

with John Waite … he’s going to sing it …

You were writing in the room with him?

I can’t

remember. Not in the room … but he was involved all the way throughout, and

no-one’s going to put that across better than him … they’re just not! I suppose

the rule of thumb is that if you’re working with people who are singers in their

career, you pretty much will end up with them singing the song … though it

doesn’t always work out like that.

Almost all your singers seem to be composers

as well … I gather Maya Saxell writes music for films.

She’s done

plenty of things. Actually she had a band in Sweden, called ‘Said the Shark’.

They’re really good!

I like the fact that

their album is called

Always

Prattling on About Wolves.

There you are

… a Swedish sense of humour.

There’s paradoxical Reid wit in

Thieves’ Road, as well as the Wild West imagery:

There’s a thousand ways to go astray when you look for fools’ gold

And you’ve got to be an honest man

when you take the thieves’ road

When you write something like ‘look for

fools’ gold’, are you aware that you’re sending a little message to Procol fans

there?

No. Not

intentionally.

You did have a phase of quoting yourself …

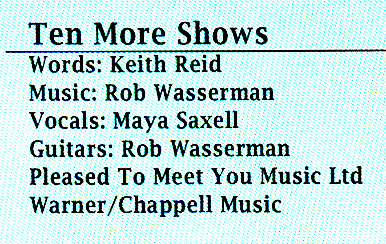

and we see ‘sink or swim’ on Ten More Shows.

I did that a

few times on The Prodigal Stranger deliberately. But the answer, now, is

definitely not.

But the album cover, and the video, and

the lawsuit song … I’m sure we’ll come on to these things … they definitely

speak to a constituency that’s immersed in your past history.

Yes.

I wonder why you’ve changed your by-line

from ‘The Keith Reid Project’ to ‘The KRP’?

I preferred

it. I don’t know if that’s been a wise choice. I didn’t understand this thing

about [search-engine] algorithms. If you type in 'The KRP' it won’t come up straight away, but

there are plenty of other KRPs

[as

well as being the TLA for numerous businesses, KRP is also clubbers’ shorthand for ‘kissing random

people’].

If you type

in 'The Keith Reid Project' it comes up straight away. So … had I known that, I

might not have done that.

Laughs.

I might

not have done it.

I preferred

it, to try and get it off of me. In an ideal world, I’d like it to be 'The KRP'

just so … I’m not quite sure why …

You’re known for not being particularly

self-promoting.

It’s not

really that, it’s just … I don’t really know why. Maybe it’s snappier.

But it distances In My Head from

your previous record, doesn’t it? Says it’s not more of the same.

Yes, I think

so, and that’s a useful by-product. I didn’t deliberately set out for it not

to

be more of the same: but I didn’t want it to be more of the same. I’d always

want to push forward.

On

the promo video for the

album, the acronym is unpacked or expanded: on screen we see ‘KRP, the

Keith Reid Project’.

On

the promo video for the

album, the acronym is unpacked or expanded: on screen we see ‘KRP, the

Keith Reid Project’.

That’s

Manfred, being mindful of algorithms. He stuck that on at the end.

So it’s Manfred who made the

Ten More Shows film

[3.17]?

No, he had

nothing to do with it.

So … who made the film?

Maya Saxell …

well it’s my idea; I spoke to Maya because she and her partner are film-makers,

and I told her what I wanted. And then she completely ignored that

… laughs …

I didn’t storyboard it, but we discussed it in great detail, and then they came

up with their own interpretation of what I was trying to communicate. But I love

it.

It's quite enigmatic in a David Lynchian

sense, with the little animal baubles hanging from threads in a forest.

No, nothing

to do with me.

And you’ve got Maya, wearing a sailor’s

outfit, with ‘Hero’ written on her hat, which I take it relates to the ‘hat full

of dreams’ in the song.

That was

totally me.

She’s rootling about on the forest floor,

and she exhumes a tiny piano.

The

film-makers came up with that bit.

Are you able to comment

on the subsequent image, where she reburies the piano, with a door-key inside

it?

No, that’s …

the magic of the movies.

Do you mean, it would destroy it to talk

about it?

Yeah …

But you can imagine the conspiracy

theorists: ‘buried key, dangling threads: key / thread = Keith Reid’’

‘It’s all

there …’

(doubtful noises)

And it’s not a great leap of

imagination to relate certain passages to Keith’s time with Procol Harum, and

the downward trajectory –

in commercial terms, at any rate – of their career.

They say you’ve got to

play to win

But life ain’t always sink or swim

Sometimes you’re playing second

fiddle

Sometimes you’re just stuck in the

middle

I point out that when you listen to Schubert you'd be daft to wonder if Fischer-Dieskau

himself is really obsessed with a Schöne Müllerin … but

on The KRP album, because there are so many different voices, the question is

bound to arise as to whether they’ve been chosen because their own history or

nature matches some particular aspect of the lyric. Or does Keith feel that the

dissonance between Maya's youth and the ‘heart full of scars … old guitar’

creates some kind of third aspect of interest – such as one might detect in

certain Elvis

Costello songs? Astutely he responds that a young woman could indeed own an old

guitar, or suffer with a scarred heart.

In fact, though, our narrator here is both

female and male, since Maya’s voice is underscored by a man’s voice throughout –

somewhat reminiscent of the way latter-day Leonard Cohen used female

shadow-singers.

Whose is the male voice? It’s not listed

in the credits.

I can’t

recall for the moment.

The video, of course, focuses

strongly on Maya, unequivocally reinforcing the feminine side. Yet she’s

impersonating a male mariner, and the 'Hero' hat, which adorns Keith’s head on the A Salty Dog cover, is

abandoned in the wood, hiding … or perhaps marking … the piano’s grave.

The song appears to be performed in a dark

wood … nothing very obviously connected with the lyrical material. You specified

that?

No, I’m not

going to take away from any of the magic … but I didn’t specify that, I will say

that much. I will tell you this, we started off with

On

the Town¸ the Gene Kelly and Frank Sinatra movie … that was the

starting point …

laughter ...

that’s where

we started.

More

laughter.

I’m reminded of the

often-mentioned yet inexplicable fact that Midnight Cowboy was the mental

springboard for The Dead Man’s Dream, but the conversation passes

to the music of the present track, and its composer.

Rob Wasserman: he was a Lou Reed sideman,

and San Francisco Conservatory of Music alumnus, I believe?

Unfortunately

he’s passed away

[1952–2016]

and he’s a

fabulous bass player, he’s got Grammies and stuff; a phenomenal musician, sorely

missed. He plays any kind of bass but he’s primarily known for playing upright

acoustic bass, and he had a band for years with Bob Weir from the Grateful Dead;

I knew him through that.

The song is marked by a simple

melody and a memorable opening hook. There's been quite a bit of overdubbing –

shaker, guiro and fretless bass alongside the acoustic guitars – yet it could

very well be performed, in an acoustic folk club setting perhaps, with just the

two voices and one strummer. The aural mood is resigned, perhaps even mellow,

and arguably this takes the edge off a lyric which, printed in the CD booklet as

all these song words are, feels more rueful.

I like what you’ve done with

William Blake: ‘see a world in a grain of sand’ becomes ‘build a wall from a

grain of sand.’

I didn’t know

that.

It wasn’t a misheard phrase?

No.

You like upending proverbs, making us

reappraise clichés and well-known quotations by distorting them slightly

[1967's 'if

music be the food of life’ pointed the way]

…

I’ve done

that in the past.

Or ‘They say the piper calls the tune’.

They don’t say that, they say the opposite.

On

one level I quite often get these things wrong! On another level maybe

subconsciously my brain must be telling me it’s better this way.

Here you tell us ‘You can buy a life right

off the shelf’? How does that relate thematically to the rest of the song?

Isn’t that

what the advertisers tell you? I think that’s what the advertisers would have us

believe.

I wonder why Ten More Shows was the song chosen for the video.

Manfred just

said, ‘Any chance of doing a video for that song?’

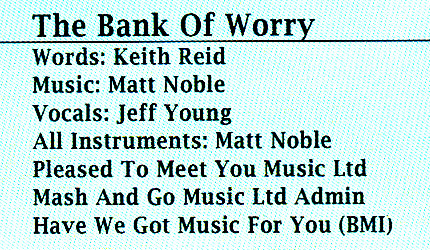

One

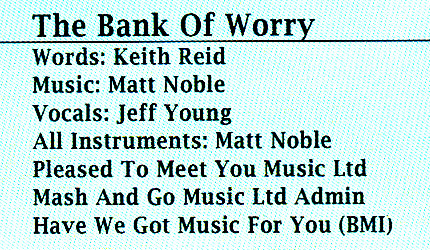

song on the album that does instantly conjure up its own visual imagery is

The Bank of Worry (3.05): it’s so easy to imagine a film in which its

genial singer, Jeff Young, beckons viewers inside the portals of some imposing

building.

One

song on the album that does instantly conjure up its own visual imagery is

The Bank of Worry (3.05): it’s so easy to imagine a film in which its

genial singer, Jeff Young, beckons viewers inside the portals of some imposing

building.

Welcome to the Bank of Worry

Everyone is in such a hurry

No-one stops to smell the roses

The Bank of Worry never closes

Reid’s lyric worries away at this

idea, stating the title phrase thirteen times in a mere twenty tightly-rhymed

lines. The music, sumptuously multitracked by composer Matt Noble, nicely

contradicts the systemic anxiety of the song words. It uses

double bass, string sounds, understated brass, electric piano, gentle drums,

congas: the texture is both rich and uncluttered, and it builds to a

true soul conclusion, the declamatory lead voice duetting with choral

responses. In the final bars we hear what may well be a guide rhythm track from

a drum machine, but there's nothing mechanical about the foregoing song

which – for my money – is over too quickly.

How did The Bank of Worry start?

Was that an overheard phrase?

With that

idea

… pause …

I was thinking about how it never stops. It’s a way of life. But it’s not a

phrase that I heard, it’s something that came to me.

In the past you’ve been a bit caustic

about bankers (viz As Strong as Samson)

This is a more generalised thing. It’s not specifically about bankers per se,

it’s about being sold worry … because it’s always there.

Could it

have been the internet of anguish, or the

national grid of unease?

Yes, but that

wouldn’t sound very poetic, would it?

I’ve known Jeff for years, a very long

time, and I’ve written songs with him in the past, I write songs with him

occasionally. He makes records himself, and he’s been in Jackson Browne’s band,

and with Steely Dan. Ah, it’s all coming back to me now … I know him from New

York, a guy who’s been around in New York for a while and he went to live in

California … he’s a good friend.

He’s also a good singer. His warm

tones recall Sam Cooke to these ears … and the voice could even make a

reassuring job of an advert for a real-world bank. Its cool, relaxed feel makes

the conclusion – which abandons the rhetoric of smooth endorsement for an abrupt

and chilling moment of truth – even more alarming:

The Bank of Worry wants your soul

The Bank of Worry’s out of control

It

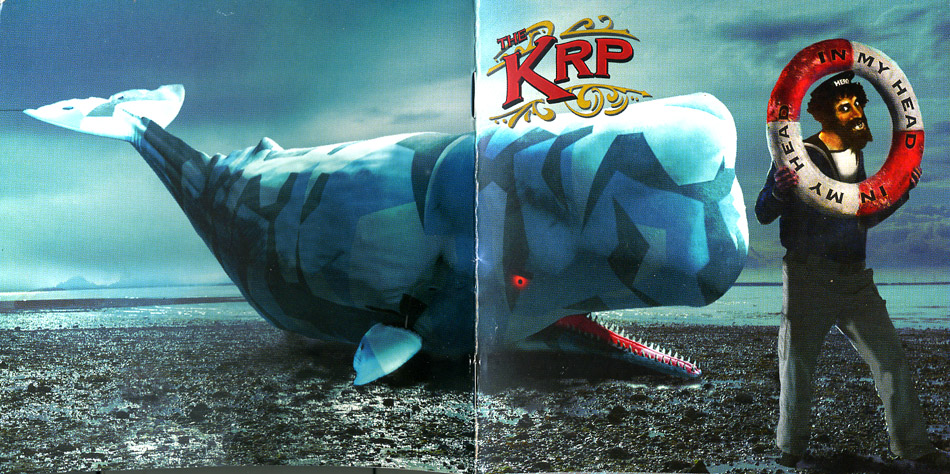

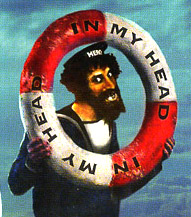

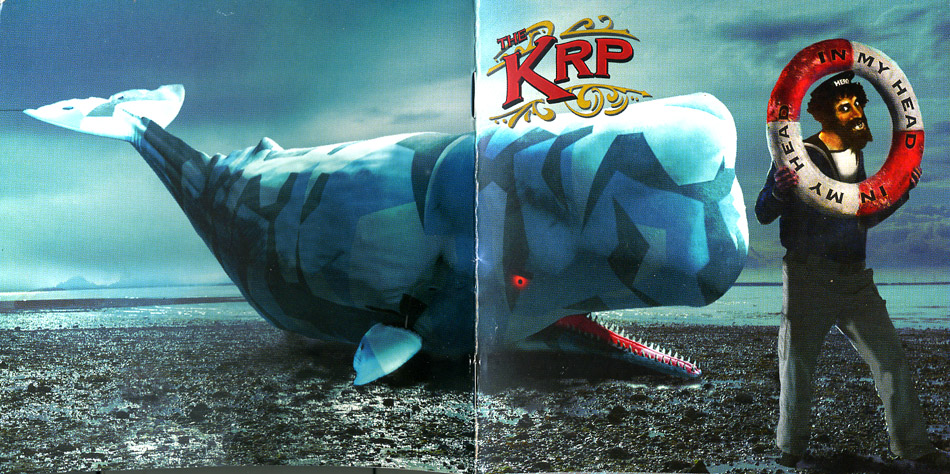

feels a good moment to turn to the rather worrying record cover, which shows a

man and a red-eyed whale. The man's body-language looks untroubled … he’s got a lifebelt, after

all … yet both he and the whale are on dry land … and they're both baring their teeth.

It

feels a good moment to turn to the rather worrying record cover, which shows a

man and a red-eyed whale. The man's body-language looks untroubled … he’s got a lifebelt, after

all … yet both he and the whale are on dry land … and they're both baring their teeth.

That’s my

idea too. Dave Cook is a good friend of mine, who very kindly did all the

graphic design.

You devised the imagery? What would you

like to say about it?

Well, what

should I be saying about it?

The album hasn’t got a picture of you

anywhere, unless people know that’s you in the lifebelt from A Salty Dog.

The top half of the 'Hero' reminds us of Procol Harum, the bottom half – the trousers

– reminds

us of the human figure from The Common Thread cover. You seem to be

turning your back on the whale ... is it another Whaling Story? We’re in a rather

featureless estuary … if the whale has been beached, it seems exceptionally

large to have been thrown up out of a completely placid sea. All in all it’s

thoroughly enigmatic.

Yes. Yeah.

I’ll buy that.

What did you specify when you contacted

Dave Cook?

I showed him

my vision, and he turned it into reality.

You had a sketch, or …

I had some

photographs. He created the whole thing. I kind of … yeah I gave him a

photograph. Everything you see there.

So somebody’s taken a photograph of you on

a foreshore with a whale?

Mirthfully.

Not exactly.

Laughs.

But I showed

him a photograph that had all those elements in.

A photo of man and whale?

Yep!

When Dickinson made the original painting,

did you pose with the lifebelt, or is it artistic licence to superimpose those two

elements.

I don’t think

I posed with the lifebuoy. I think it was just a picture and she added those

other elements afterwards.

But these images do suggest that you want

the album to be interpreted, or construed, or evaluated, in connection with

Procol Harum ...

Mm hmm. I

don’t know.

Well you’re saying, here’s the cover of

A Salty Dog, arguably the most famous Procol album cover …

Well I’m

saying ‘Here’s me!’

Notwithstanding most people don’t know

it’s you?

Ah well, you

can enlighten them! I like the whole booklet. I think he’s done a fantastic job

[we talk about the way the seashore runs through all the pages]

So it’s not

Southend-on-Sea?

No! Although

I don’t know why I’m saying that. I don’t know where it is. I love the artwork.

Whereas I said it looked like a man

walking away from a whale, in fact it could be that the whale, with his red eyes

and jaws gaping, is baring his teeth ready to assail the human figure.

Well, this is

beauty of art, isn’t it, you can ! Two people can look at the same picture and

get different things.

All we care about is what you get from it,

and what you put into it.

Well, my job

is to just put it out there.

I don’t think you can rely on the same

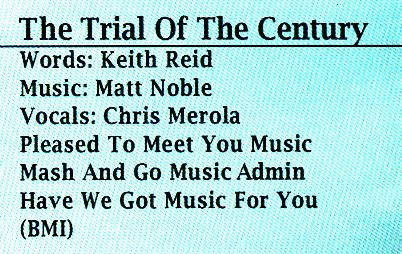

trope when it comes to Trial of the Century.

What trope is

that?

The one where you respond with ‘I must

have thought it was valid at the time’. The Teflon reflex, ‘You can’t stick

anything on me, guv.’

Many times I’ve brought parties of students here to London

museums and galleries; when they say something like ‘Why did Picasso do this?’ I

have to answer with plausible tangents, ‘some of these images crop up a lot in

his work, look at the line, the colour, the balance, compare it with earlier and

later stuff, see how it makes you feel.’ But I warn them. ‘As to what it’s

intended to mean, we’ll never know … he’s not here to tell us.’

But in the case of Keith Reid, luckily you

are here to tell us … if you choose to.

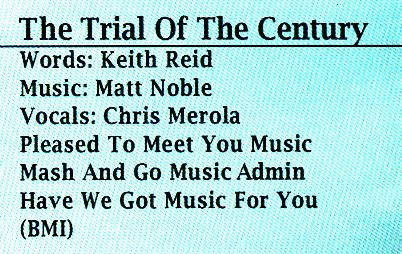

The

Trial of the Century [3.34]

seems to be explicitly about recent, or recent-ish,

legal events.

The

Trial of the Century [3.34]

seems to be explicitly about recent, or recent-ish,

legal events.

Oh, for sure. No question about

it.

You ask lots of rhetorical questions – ‘was he

excluded, or simply deluded, a wolf in sheep’s clothing or merely a sheep’ – but

you don’t commit yourself beyond raising the question.

Well, that’s it, that’s my job. I

wanted to … well I won’t say I wanted to, I was impelled to write

a song about that situation, about my experiences ...

As you said when we started talking, ‘these

songs are about me’. Is this song going to add to people’s understanding of the

Whiter Shade of Pale lawsuit?

Ummmm ... I don’t know. They’ll

certainly hear something about it from my point of view

(laughs).

In fact the song uses the typical

Reid trick of multiple viewpoints: for instance, though ‘slick’, ‘glib’,

‘mirrors and smoke’ may imply that the currency of the lawsuit was illusions,

‘the cat's out the bag’ suggests a revelation of truth. No doubt some will suppose this

‘cat’ refers to Procul Harun, the band’s founding feline. And elsewhere there

are lines like ‘Song sounds familiar, they’re robbing the grave’ that don’t map

conveniently on to the received lawsuit facts (though this instance may remind

us of the exhumation and reburial in Ten More Shows).

Even in the lines that appear to

invite an obvious interpretation, one quickly realises there may be more than

one candidate to inhabit the pronoun ‘he’ … the defendants, plaintiffs, counsels

and judge were all of the male gender. ‘With so many lawyers the truth’s hard to

find’ could be interpreted as ‘even with such a wealth of legal expertise the

truth is elusive’ or else ‘the more lawyers you employ the less likely you are

to get to the truth’.

The words …

see here for the

entire text … are sung with feeling by Chris Merola.

Did you feel Chris Merola

'inhabits' this lyric? Did he know the legal background to the trial?

He didn’t, not at all. And

actually a few different people sang that song, just a few different people,

nobody that you’d know. A few different people in the Bronxville world.

When other people tackled it, did they get as

far as finished vocals?

Yes. I worked on this tune quite a

few times, and Chris’s is the one I liked best.

BtP reviewed

Chris's album

Straight Answer in a Crooked Town. And of course he

plays twelve-string on The Prodigal Stranger … The Hand that Rocks the

Cradle, as I remember.

I’m sure he does … if he said so.

He’s a lovely guy. He’s quite good, I think. I met him through Matt Noble.

Matt who wrote the music here, and has

half-a-dozen Procol co-writes to his name. I haven’t worked

out whether you allotted particular lyrics to particular composers.

Not deliberately. Not on purpose. Not in

terms of thinking, ‘Oh, this will be good for … so-and-so’. Invariably, if you

think that would be good – to get so-and-so in to do it – it turns out that it’s

not (laughs). But this was just one of the songs

… I wrote quite a few songs with Matt, and that was just one of them.

You don’t specify who’s playing what on this

one.

It’s all Matt.

The song starts with clanking

piano triplets accompanying the slightly gruff tones of the singer; a synth bass comes

in for the second verse, and the drums power into the chorus ... in which we

notice some hovering Hammond. A dark scar of 'cello heralds the third verse,

which is again haunted by the organ. The doubled voice gives weight to the

chorus, then the first instrumental break ... a sliver of Bach ... is taken by string sounds and a

glittering harpsichord. Everything winds down to piano and voice again, with

intermittent drum entries that will please PH fans. When the Bach motif returns

its duration is ever-briefer, curtailed by voices hollering the title; then the

whole weighty piece collapses into the ambiguously-intended refrain of 'Give me

break': it's very effective.

Even

though you carefully don’t name names in the lyric, you put a layer of

conspicuous Hammond organ on it, with very characteristic drawbar settings that

counterfeit that classic plangent, nasal Procol sound. And then there’s the Bach

satire, when you bodge a splinter of

Jesu Joy of Man’s

Desiring into the middle of it.

(laughter)

We tried a couple of things, and Matt did that and I said,

'Oh, I

really like that.'

So it was your idea to sling some Bach in?

We were just playing around,

trying to do something à propos. And I wanted to emphasise it as well, as

I recall.

There’s another mixed-up proverb, your own take

on ‘Give a man enough rope and he’ll hang himself’.

I was trying to express that idea, but it would have sounded clumsy. I’m saying

that in my own words. ‘Don’t need a hangman when you’ve got enough rope’

And when you decide to make a record, you

probably type out some song words … do you send 'Song A' to several composers and

see if it strikes a note with them …

No, it’s not quite like that, because it’s an

accumulation … I’m trying to think how it came about

… pause …

those songs, when I was doing them with Matt … those were days I was working

with him, and I had a bunch of lyrics and we just started working on things and

that one started to come together.

So it doesn’t mean there’s

a Steve Booker setting of this song in the bin somewhere?

Oh no, no no no, not at all.

I think we have a lingering

impression inherited from Procol days that sometimes a lyric got set by more

than one person: Crucifiction Lane, for instance?

Yes, but that was a slightly

different situation. I mean you could sit down and work on a song with

one person and think, ‘It hasn’t worked out, I’m going to try it again with

somebody else.’ I’m sure people do do that, but it’s not really fair, if

you see what I mean. If you sit down and work with somebody, and that happens,

you probably ditch the whole thing: it’s just something that didn’t work out.

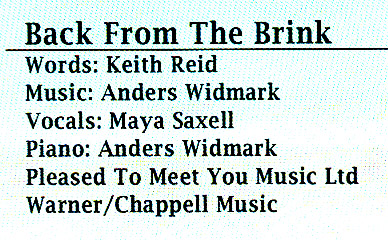

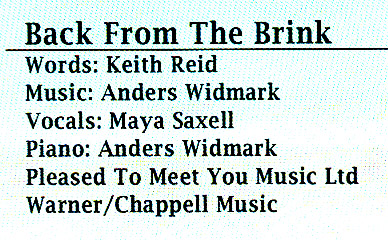

A song that definitively did

work out, to this listener’s ears, is Back from the Brink (3.47).

This is a doom-laden miniature, voice and piano only, which

may strike some listeners as a grandchild of

Barnyard Story …

though composer Anders

Widmark’s piano is riddled with sprightly rhythms, countering the slow plaint of

Maya Saxell’s vocal. It’s an old-fashioned, artful tune, decorated with

intriguing intervals and variant harmonies that keep the ear in a constant state

of engagement and surprise.

Scandinavian readers may well know this

song already, from the Mikael Rickfors version. His 2004 Lush Life album also

features Dance with Me, which is freshly interpreted as the penultimate track on

In My Head.

Yes those two songs were written

much earlier, but they weren’t in my mind back then, as candidates, when I was choosing

material for The Common Thread. Michael is a very fine singer. But I

haven’t heard his versions for ages: they didn’t play any part in my thinking

about In My Head.

It could be argued that Rickfors’s

regular, metrical delivery undersells the lyric. Its topic, after all, is a

super-serious one – mountains of pain, the threat of imminent catastrophe, the

ubiquitous passing of the buck – and the carefully-planned rhymes don’t want to run the risk of sounding like

doggerel.

We go lighting a fuse

When there’s so much to lose

Grow that mountain of pain ever faster

Let’s draw back from the brink

Cos we don’t wanna sink

And it’s all going to end in disaster.

Rickfors's workmanlike delivery, over a

backing of piano, upright bass, drums and a handful of brass, lacks Maya’s sense

of exploration of the ideas in the song. Her freer, more introverted delivery

gives a properly thought-provoking weight to the cunning irregularities of the

lyric, in which we hear sometimes ‘mountain of pain’ and sometimes ‘mountain of

shame’, sometimes ‘don’t wanna sink’ and sometimes ‘don’t wanna think’.

The

opening line, ‘Put away those childhood toys’ arguably describes what’s

happening in the Ten More Shows

video. Alliterative decoration is attractively handled – ‘bricks … bats’,

‘tricks … traps’ – yet Reid also sidesteps that effect, giving us ‘trinkets

and bangles and beads’, dodging the clichéd ‘bauble’. To this reviewer it’s one

of the finest lyrics on the record, eschewing songwriterly formulae, yet obeying

its own inner logic.

The

opening line, ‘Put away those childhood toys’ arguably describes what’s

happening in the Ten More Shows

video. Alliterative decoration is attractively handled – ‘bricks … bats’,

‘tricks … traps’ – yet Reid also sidesteps that effect, giving us ‘trinkets

and bangles and beads’, dodging the clichéd ‘bauble’. To this reviewer it’s one

of the finest lyrics on the record, eschewing songwriterly formulae, yet obeying

its own inner logic.

It’s a bit like the older Reid style, ‘all going

to end in disaster,’ an undertow of pessimism … but here embodying a call to come ‘back

from the brink.’ Which makes a great hook.

You know, The Bank of Worry started out from that line, but

Back from the Brink was different … that

line came along as I wrote the song.

The sound of the track is unique

on the album. Maya sings her own, haunting harmony vocal, and the skipping,

rhythmically playful piano (its forty-second coda reminiscent of Jacques

Loussier) appears distinctly treated. Keith explains:

No, I know what you mean, it’s the same piano

as in the other two piano tracks. I know what you mean. It sounds as if it’s got

an effect on it, but it hasn’t. It just happened like that. There were really

weird echoes in the room. It’s not digital. Some magical force took over.

The piano tracks were done over a

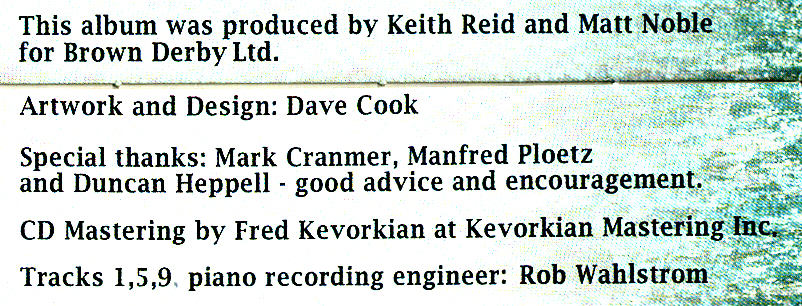

few days but this is the only one on which that effect was observed. The

recording engineer on the Anders Widmark numbers receives a special credit; but

Keith concedes that there’s a mistake in its track-references..

It should be 1, 7, 9. I think what

happened there is that this running order got changed a few times. You’ve spotted a mistake. Maybe you’ll be the only person to spot

that!

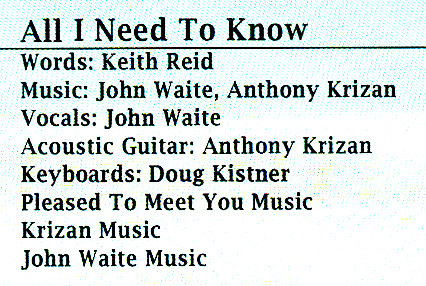

All

I Need to Know (5.06) starts gently with a couple of acoustic

guitars, John Waite's character-filled voice picked out with distant, watery reverb.

Doug Kistner's piano lends emphasis, and vibrato string sounds soon well up from

the background, as the temperature of Waite's singing rises. The lack of drums

is notable, and the guitars provide all the necessary rhythmical impetus.

All

I Need to Know (5.06) starts gently with a couple of acoustic

guitars, John Waite's character-filled voice picked out with distant, watery reverb.

Doug Kistner's piano lends emphasis, and vibrato string sounds soon well up from

the background, as the temperature of Waite's singing rises. The lack of drums

is notable, and the guitars provide all the necessary rhythmical impetus.

My love

lies in shadows

Ten silent fathoms deep

I swim through dark waters

to watch her sleep

This reminds me faintly of

Love Minus Zero /

No Limit: ‘My love she speaks like silence.’

I love that, that’s a great one. I

haven’t heard that for years.

It’s as if a drop of Dylan has

fertilised the soil from which Broken Barricades once grew: but

here the imagery of tides, seashells, and wastelands is redemptive.

What’s the story of this one?

Once again, I met John Waite

though Frankie LaRocca back in the day, and wrote songs with him for his record.

We just remained friends and occasional writers.

Waite's In God’s Shadow

is a favourite off The Common Thread.

Yes, I like that one a lot. All

I Need to Know? I was working with John and Anthony and they had the tune

going, and basically I wrote that in New York, and I think I just went back to

my loft … I had the tune, not completed, but the musical basis was there.

What’s that glittering sound, in later

verses, like a glass

harmonica?

It’s some kind of keyboardy thing.

Waite's performance is emotive but

not overdone: he has an incisive yet sympathetic voice which compels any

listener's attention. Core aspects of this song feel

reminiscent of Gary Brooker’s recent solo track, Somewhen,

which posits the reunion of lovers at the end of their mortal life, though I

don’t ask Keith if he’s heard that.

I give

her my very heart … till death us part ..

but someday I’ll be with her and that’s

all I need to know.

If this level of directness and emotional honesty doesn’t sound like Keith Reid

... it may be time to revise your opinion of his range!

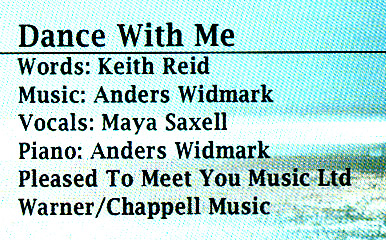

And the same applies to

Dance with Me (4.04)

And the same applies to

Dance with Me (4.04)

Won’t you

dance with me, close to me …

when you

dance with me nothing else feels real

In Maya Saxell’s halting, inward treatment, a lyric that arguably bordered

on the sentimental in Mikael Rickfors’s 2004 version now becomes a sensual and

existential investigation of the core question, ‘Is it only dreams that we pursue?’

One life, one wish …

that will do …’.

A settled wisdom has replaced the

signature nihilism of Reid’s early lyrical excursions; and although there’s

still an acknowledgment of uncertainty, the poet now finds reassurance and

adventure in doubt.

Life … it’s not being afraid … it’s ‘don’t know for

sure’

'New songs are old songs' is a

paradoxical proposition, and runs counter to both sides of the argument in the

title song of this collection. But Saxell's voice draws us into this song about

songs, and purges any saccharine potential from lines like 'your song is my song'

thanks to the mysterious intimacy of her delivery. 'She sings it great,' says Reid, a

couple of times. And Widmark plays it great too, voicing his own chords with

delicious attention to detail ... basslines, tripletty fills, occasional

passages played hymnally straight, sudden 'Piccadilly thirds' ... it's

compelling listening.

I tried ten zillion instruments on

that track, then chucked them all out. On quite a few of these tunes I tried all

kinds of stuff. Definitely on the piano ones, and some of the others, just

trying different stuff out to see what worked. Strings, drums, bass, you name

it.

They all started with a full performance on

piano?

I didn’t think they added anything.

Laughter.

I certainly tried!

I don’t feel the loss.

No, there’s a lot of depth to his

playing, and the harmonics.

Keith tells me that this Dance with

Me was not made with reference to the Rickfors version, nor was the decision to

eschew additional instruments related in any way to the 2004 record’s reliance

on upright bass, brushed kit, steel guitar, sax and trumpet to suggest a

cocktail-bar ambience. But as he rightly observes,

Even if you pared all [Rickfors’s]

stuff down to voice and solo piano, the feel would be very different.

It certainly would. Widmark is a

very inventive player, exploring the full range of the piano, and one gets

a sense of the restraint he habitually practises when, suddenly, at about the

three-minute mark, he erupts into a wild piano break, as unexpected and effective as the classic moment on

The Hissing of Summer Lawns where Joni Mitchell’s Harry’s House is interrupted

and offset by the jazz standard Centrepiece. Widmark's exhalations,

guttural exclamations and other Oscar Peterson-like behaviours are fearlessly commemorated in

this exciting recording. Then he reins himself back, and Maya returns – almost

an afterthought – for a couple of lines which restore the original feel of the

song.

You can hear him banging the floor

with his foot, which is great.

As producer, had you suggested a piano break at

that point?

No no, but actually funnily enough

with that tune he was used to doing it much more up-tempo. The way he envisaged

that tune, and the way we did it, are very different. Because he envisaged it as

an up-tempo rock and roll tune, and I said ‘Do it like this, and put that bit as

the opening’. I had quite a lot to do with the arrangement of that tune. Nothing

to do with the performance, but a lot to do with the way it turned out, and it

wasn’t how Anders had envisaged it whatsoever. In his mind it sounded more like

The Who or something like that.

So as

producer Keith Reid pulled things back from the brink, as it were.

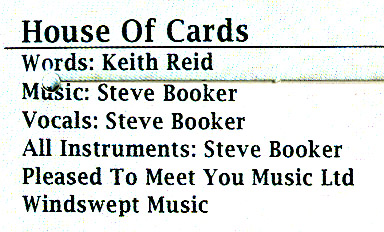

Thus the record, which represents a lot of pruning and winnowing, ends with

another Booker/Reid

song, House of Cards (4.43).

Guitar, bass, gentle drums, and some organ hovering about in

the background, create an initial wash of sound, which recedes as Steve Booker's warm

tones take centre stage, venturing convincingly into his high register from time

to time. The chords in the nicely-harmonised chorus are unpredictable, the hook

catchy: the chromatic bassline is an appealing feature too.

Thus the record, which represents a lot of pruning and winnowing, ends with

another Booker/Reid

song, House of Cards (4.43).

Guitar, bass, gentle drums, and some organ hovering about in

the background, create an initial wash of sound, which recedes as Steve Booker's warm

tones take centre stage, venturing convincingly into his high register from time

to time. The chords in the nicely-harmonised chorus are unpredictable, the hook

catchy: the chromatic bassline is an appealing feature too.

In a carefully-engineered lyric Keith takes a wander through

his playing cards, conflating gambling lingo with the fragility of a house of

cards, and also using the ‘heart’ image as a pivot into the world of a doomed

romance.

Love has many faces

Tell me how does it feel

when you’re holding aces

you can’t deal.

House

of Cards … not sure I've entirely warmed to this one yet, though the chorus is nice.

What are its strengths from your point of view?

I just liked it.

I could imagine someone else taking this one up.

Maybe somebody else will? Could you do that

for me, tout it around?

Laughter

Are these songs calling-cards?

I didn’t write them with that

intention. Maybe House of Cards is a

bit more mainstream.

The romance narrative is

judiciously defocused so that the listener can find her or his own resonances:

no doubt some will seek to inscribe what they

think they know of the poet’s history on to the final lines:

And the

world you made

Has all gone up in flames

The best hand’s been played

And it’s too late to save

Your house of cards

As on The Common

Thread, it’s a

Booker/Reid song that closes this album. I wonder how Keith resisted the

temptation to close symmetrically, bookending the whole show with another Maya Saxell

song.

I felt House of Cards

couldn’t have been anywhere else but the last track.

You told me that the running order for the first

album had exercised you almost as much as any other aspect of it. Here you had

four Maya ones to spread out … did that make it harder?

Let me just say that it went

through quite a lot of juggling, and even when I delivered the record to Manfred

he had his own ideas, and I listened to a few other people as well. I always

wanted it to open with This Space is Vacant and everything else was just

juggling to see what fitted where musically. I tried many permutations.

And (as with Procol) the running order is

determined according to musical considerations, rather than lyrical ones?

Totally. People’s keys, voices ….

you know, whose voice sounds good following someone else’s voice. No lyrical

reasons.

What

have I omitted to ask you?

I’ve no idea. You’re pretty much the first

person I’ve ever spoken to about it. I’ve no idea what anyone would make of it,

really. Laughter.

I tell Keith that I realise my

response is pretty skewed, partly since I've taken a strong interest in his writing since I was fourteen, and

partly since I've spent many decades being paid to help readers see the

trees, real and imaginary, in many intriguing literary woods.

I tell Keith that I realise my

response is pretty skewed, partly since I've taken a strong interest in his writing since I was fourteen, and

partly since I've spent many decades being paid to help readers see the

trees, real and imaginary, in many intriguing literary woods.

‘I’m always impressed with your

painstaking approach, always impressed,’ he says; but we do agree that the

record is not aimed at a constituency that will especially want to milk it for Procol

allusions!

Yes, in an ideal world you want

people to know nothing about it, and like it. You want someone to like it

because they come to it with no preconceptions.

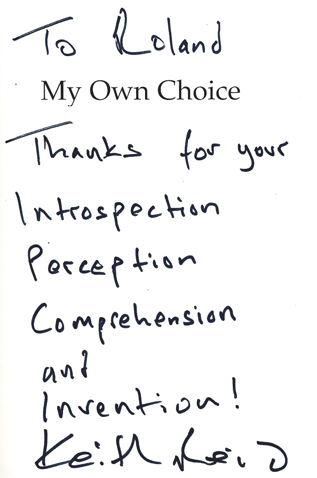

By now night is falling, and November

is making itself felt: even dawn-swimmers in The Serpentine start to feel a little chilly. As we prepare to leave the Madjeski Courtyard, a

discerning V&A mouse emerges from the shrubbery in search of crumbs fallen from the poet’s table. ‘At least it’s not a rat,’ Keith observes.

I don’t want to wait ten years for

the next Reid solo album (Will its title rhyme? Is there a lurking joke here, a

long series – The Common Thread, In My Head – whose dark punchline ends with the word Dead?). I want Keith to book a

venue, a

piano, and a guitar, and present Anders Widmark, Maya Saxell and John Waite in

concert … to hear these very interesting songs in front of a live audience would complete them.

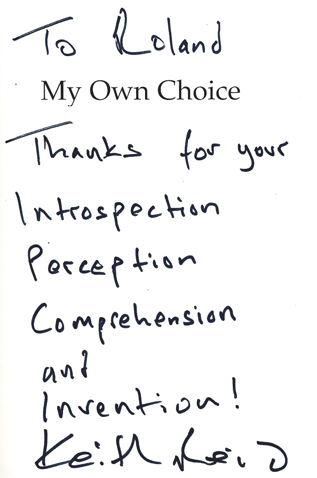

But I don’t mention this: he’s busy signing my copy of his anthology,

My Own

Choice, published in 2000 by Charnel House.

I'm glad Reid is still working, doing such interesting stuff, and happy to have

been among the first to talk with him about the new record.

Good luck with The KRP. It’s not a veiled reference to

Mr Krup, is it?

I wasn’t thinking that.

It doesn’t matter whether you were consciously thinking it

… laughter.

When I read Keith's inscription on the

title-page, I notice that his instinctive propensity to rhyme has enshrined some

mischief at the expense of my instinctive propensity to over-interpret. 'Guilty

as charged,' I tell him, as we shake hands. 'Take care, man,' is his valediction.

Then, as aforesaid, he’s off the

pavement and into

the traffic.

Buy In My Head

from Amazon.co.uk or

from Amazon.com

Keith is no stranger, however, to

nearby Hyde Park,

where, he tells me, he belonged for a year to the

Serpentine Swimming Club, and

swam there daily at 7 am. ‘In winter you can’t stay in for long, of course, but

the blood rushes out to your skin …’. Sounds exhilarating, I say, but is it good

for you? With a gesture straight out of Waiting for Godot he indicates

his own person, inviting me to judge for myself.

Keith is no stranger, however, to

nearby Hyde Park,

where, he tells me, he belonged for a year to the

Serpentine Swimming Club, and

swam there daily at 7 am. ‘In winter you can’t stay in for long, of course, but

the blood rushes out to your skin …’. Sounds exhilarating, I say, but is it good

for you? With a gesture straight out of Waiting for Godot he indicates

his own person, inviting me to judge for myself. Our topic – pretty well

exclusively – is his new album,

Our topic – pretty well

exclusively – is his new album,  The

first track on the album is a huge surprise, I tell him. This Space is

Vacant (4.10) – intimately sung by Maya Saxell, and accompanied

exquisitely at the piano by Anders Widmark, a big name in Swedish jazz – marks a

major departure from the tone and density of The Common Thread. I ask if

Maya is related to 2008 Reid collaborator Michael Saxell, the Grammy-award

winning Swedish hit-meister. The answer comes back, immediate, fluent.

The

first track on the album is a huge surprise, I tell him. This Space is

Vacant (4.10) – intimately sung by Maya Saxell, and accompanied

exquisitely at the piano by Anders Widmark, a big name in Swedish jazz – marks a

major departure from the tone and density of The Common Thread. I ask if

Maya is related to 2008 Reid collaborator Michael Saxell, the Grammy-award

winning Swedish hit-meister. The answer comes back, immediate, fluent. Needless

to say the second track, which gives its name to the whole collection, presents

an enormous contrast. Prominent lead guitar (textural, not really melodic, and

sometimes recorded backwards), groovy beats, and an assertively mobile bass line are provided by The Spin

Doctors’ sometime guitarist Anthony Krizan, who also sings.

Needless

to say the second track, which gives its name to the whole collection, presents

an enormous contrast. Prominent lead guitar (textural, not really melodic, and

sometimes recorded backwards), groovy beats, and an assertively mobile bass line are provided by The Spin

Doctors’ sometime guitarist Anthony Krizan, who also sings.

Thieves’

Road (4.45) doesn’t concern itself with jail, nor the courts, but offers

a kind of admonition to an unnamed ‘you’ who ‘… rode your winning streak down

where the crossroads meet’. The language remains somewhat indeterminate, and,

like the music, doesn’t offer too many surprises. Sprightly acoustic rhythm

guitar, solid four-to-the bar bass, rhythm shakers, piano and languid, slightly-distant lead guitar offer a pleasing,

if unvarying, listening experience. By

comparison with the foregoing numbers, this Booker/Reid song seems a more

mainstream piece of work.

Thieves’

Road (4.45) doesn’t concern itself with jail, nor the courts, but offers

a kind of admonition to an unnamed ‘you’ who ‘… rode your winning streak down

where the crossroads meet’. The language remains somewhat indeterminate, and,

like the music, doesn’t offer too many surprises. Sprightly acoustic rhythm

guitar, solid four-to-the bar bass, rhythm shakers, piano and languid, slightly-distant lead guitar offer a pleasing,

if unvarying, listening experience. By

comparison with the foregoing numbers, this Booker/Reid song seems a more

mainstream piece of work. On

On

One

song on the album that does instantly conjure up its own visual imagery is

The Bank of Worry (3.05): it’s so easy to imagine a film in which its

genial singer, Jeff Young, beckons viewers inside the portals of some imposing

building.

One

song on the album that does instantly conjure up its own visual imagery is

The Bank of Worry (3.05): it’s so easy to imagine a film in which its

genial singer, Jeff Young, beckons viewers inside the portals of some imposing

building. It

feels a good moment to turn to the rather worrying record cover, which shows a

man and a red-eyed whale. The man's body-language looks untroubled … he’s got a lifebelt, after

all … yet both he and the whale are on dry land … and they're both baring their teeth.

It

feels a good moment to turn to the rather worrying record cover, which shows a

man and a red-eyed whale. The man's body-language looks untroubled … he’s got a lifebelt, after

all … yet both he and the whale are on dry land … and they're both baring their teeth.  The

Trial of the Century [3.34]

seems to be explicitly about recent, or recent-ish,

The

Trial of the Century [3.34]

seems to be explicitly about recent, or recent-ish,

The

opening line, ‘Put away those childhood toys’ arguably describes what’s

happening in the Ten More Shows

video. Alliterative decoration is attractively handled – ‘bricks … bats’,

‘tricks … traps’ – yet Reid also sidesteps that effect, giving us ‘trinkets

and bangles and beads’, dodging the clichéd ‘bauble’. To this reviewer it’s one

of the finest lyrics on the record, eschewing songwriterly formulae, yet obeying

its own inner logic.

The

opening line, ‘Put away those childhood toys’ arguably describes what’s

happening in the Ten More Shows

video. Alliterative decoration is attractively handled – ‘bricks … bats’,

‘tricks … traps’ – yet Reid also sidesteps that effect, giving us ‘trinkets

and bangles and beads’, dodging the clichéd ‘bauble’. To this reviewer it’s one

of the finest lyrics on the record, eschewing songwriterly formulae, yet obeying

its own inner logic. All

I Need to Know (5.06) starts gently with a couple of acoustic

guitars, John Waite's character-filled voice picked out with distant, watery reverb.

Doug Kistner's piano lends emphasis, and vibrato string sounds soon well up from

the background, as the temperature of Waite's singing rises. The lack of drums

is notable, and the guitars provide all the necessary rhythmical impetus.

All

I Need to Know (5.06) starts gently with a couple of acoustic

guitars, John Waite's character-filled voice picked out with distant, watery reverb.

Doug Kistner's piano lends emphasis, and vibrato string sounds soon well up from

the background, as the temperature of Waite's singing rises. The lack of drums

is notable, and the guitars provide all the necessary rhythmical impetus.  And the same applies to

Dance with Me (4.04)

And the same applies to

Dance with Me (4.04) Thus the record, which represents a lot of pruning and winnowing, ends with

Thus the record, which represents a lot of pruning and winnowing, ends with

I tell Keith that I realise my

response is pretty skewed, partly since I've taken a strong interest in his writing since I was fourteen, and

partly since I've spent many decades being paid to help readers see the

trees, real and imaginary, in many intriguing literary woods.

I tell Keith that I realise my

response is pretty skewed, partly since I've taken a strong interest in his writing since I was fourteen, and

partly since I've spent many decades being paid to help readers see the

trees, real and imaginary, in many intriguing literary woods.