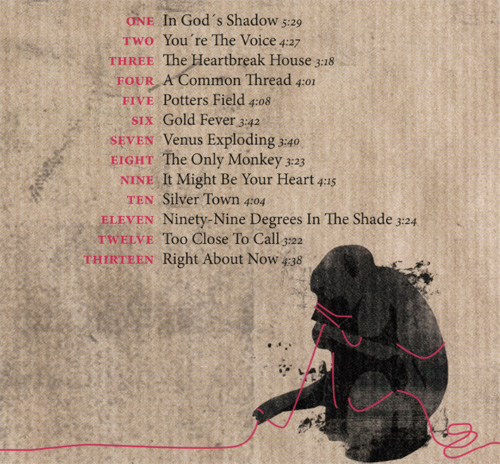

From Cerdes to Silver Town

BtP unravels The Common Thread CD from The Keith Reid Project

After

all this time ... more than four decades since his pen first

enthralled the listening world ... a Keith Reid solo album!

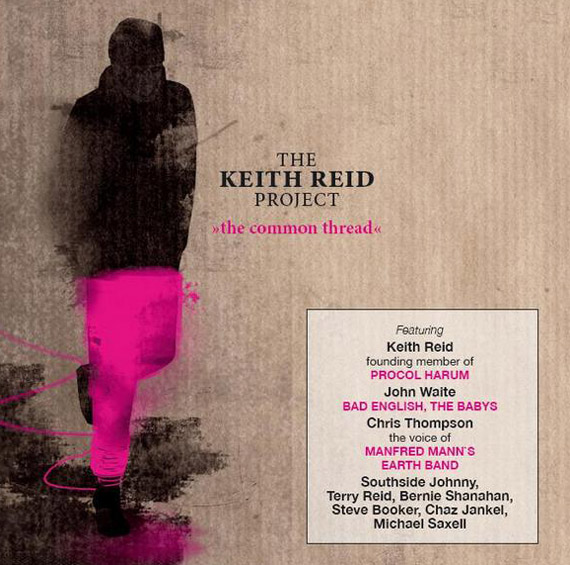

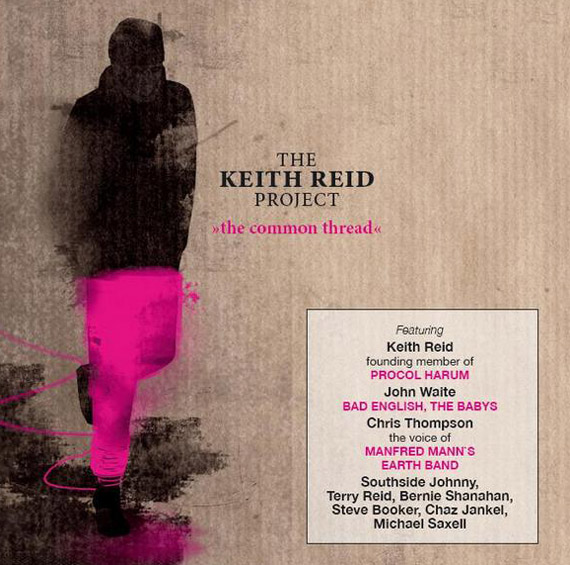

And a solo album of a most unusual sort, held together by the writing of the

words, rather than by any particular composer or performer: it harbours music of

many styles, and features many voices: and it's all very appetising, moreish

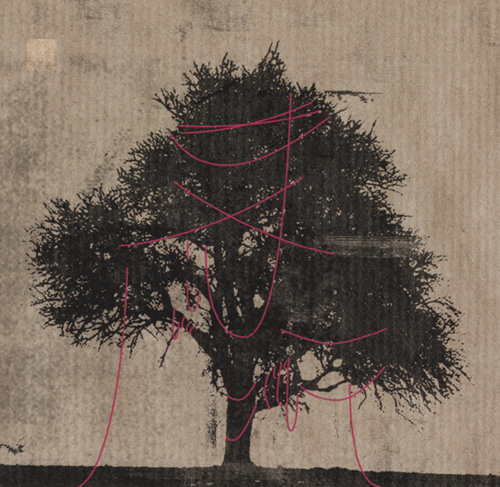

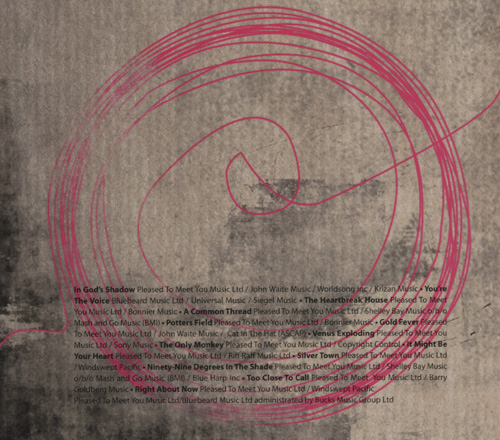

stuff. Reid himself is the eponymous 'thread', and the CD graphics

(by guitarist / Dylan-illustrator

Eugen Kern-Emden) make this clear: on the front cover a pink-trousered figure – an everyman

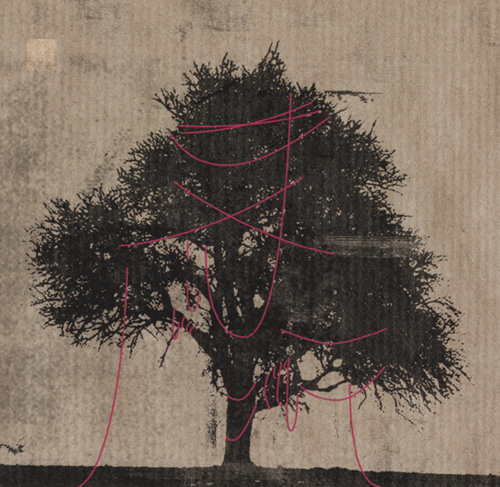

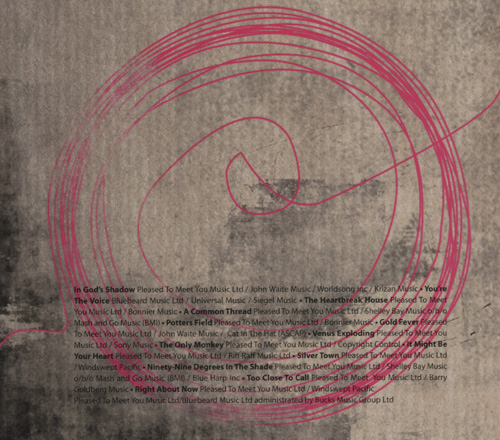

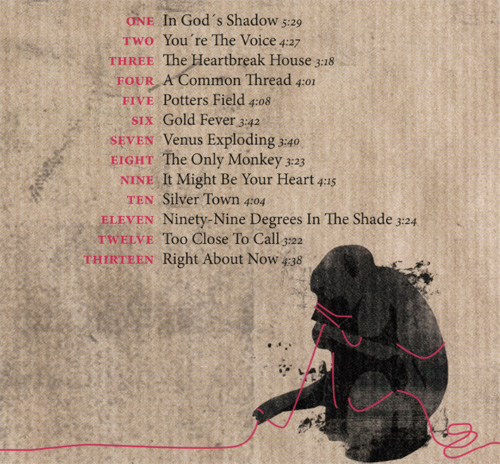

figure, or the lyricist himself? – walks into the frame, trailing a thread that on other pages appears festooned among the branches of a

tree (no worm in sight), then encircling the publisher-details, and latterly, on the

back cover, in the grasp of a crouching ape. Is the ape reeling this umbilicus

in, or paying it out? The relationship between man and monkey will be made

explicit as the album unfurls!

And a solo album of a most unusual sort, held together by the writing of the

words, rather than by any particular composer or performer: it harbours music of

many styles, and features many voices: and it's all very appetising, moreish

stuff. Reid himself is the eponymous 'thread', and the CD graphics

(by guitarist / Dylan-illustrator

Eugen Kern-Emden) make this clear: on the front cover a pink-trousered figure – an everyman

figure, or the lyricist himself? – walks into the frame, trailing a thread that on other pages appears festooned among the branches of a

tree (no worm in sight), then encircling the publisher-details, and latterly, on the

back cover, in the grasp of a crouching ape. Is the ape reeling this umbilicus

in, or paying it out? The relationship between man and monkey will be made

explicit as the album unfurls!

There is a further, unseen thread: Reid's words as they have unspooled

progressively in

the minds of Procol Harum

fans, gradually shifting in tone – from dreamlike through doomladen towards

danceability, from sensual through self-referential towards sentimentality. To

those who grew up listening to early Procol his lyrics seemed axiomatically

irreducible, stubbornly resisting any single meaning: they were allusive,

rhetorical, spiked with mischievous humour and threatened by an undertow of

melancholy verging at times on the nihilistic. Only in later albums did his

writing become more transparent: songs such as One More Time on

The Prodigal Stranger, for instance, might have been written for and sung

by any band, and seemed less Procolesque in consequence. But there is more to

Reid than his Procol work, as

this page attests: we

have latterly come to know him as a jobbing songsmith, providing lyrics for a variety of

singers and composers, working in popular markets where we could scarcely expect to find

the Valkyries, pygmies, and other typewriter torments that

distinguished the Old Testament Procol years.

So, to the current album, in which his collaborations with some top

singers and composers are released under the umbrella title of 'The Keith

Reid Project'. It opens very strongly with John Waite's emotional and appealingly

melodic In God's Shadow, a powerful set of

words that fans already know from Reid's

My Own Choice

lyric-book collection. There are some small differences of emphasis between this

song and the printed version ('but' for 'and' and so on): but intriguingly

Waite's version adds a couple of

lines to the earlier text, and these appear in parentheses in the CD booklet.

There's a more significant change too, where 'this matter of existence, our ship

wasn't built to last' becomes 'this matter of resistance, our ship was

built to last': perhaps singability trumped significance when these words made

it from the page into the recording studio; or perhaps, as Keith now suspects,

there was a typo in Charnel House's printed edition. The 2008 release is, of course, a

different recording from the one issued on Waite's 1995 album, Temple Bar:

none of the music on The Common Thread has been officially heard before. The

1995 recording was

rather heavier, with piano and a more prominent guitar part weaving around the

voice. The new version is a very radio-friendly track:

lead guitar rides over strummed acoustics, and bass and drums give a strong

forward impetus: the harmonies are slightly Procolesque as the bassline rides up

through the chord-inversions into a very hummable and powerful chorus. There's much here

to please any Procol fan: 'we're sailing out on troubled seas: nail our colours to the mast'

as well as the existential content, as 'life's certainties slip

away' and we finally 'lie down in God's shadow'. The current version is dedicated to

Frankie LaRocka, the

New York A&R man who is also name-checked on The Prodigal Stranger liner-note:

as John Waite's drummer, he introduced Reid to the musicians who wrote this song

(Waite is British by birth, but has lived in the USA for many years). It would

be nice to know exactly who plays in the band but, as with all subsequent

pieces, these details are omitted: 'Played arranged and produced by ...

' is the formula for every track, and the names following are usually those of

the composers and Reid himself. This throws the emphasis squarely on the singing

and the writing, which is evidently the compilers' intention.

So, to the current album, in which his collaborations with some top

singers and composers are released under the umbrella title of 'The Keith

Reid Project'. It opens very strongly with John Waite's emotional and appealingly

melodic In God's Shadow, a powerful set of

words that fans already know from Reid's

My Own Choice

lyric-book collection. There are some small differences of emphasis between this

song and the printed version ('but' for 'and' and so on): but intriguingly

Waite's version adds a couple of

lines to the earlier text, and these appear in parentheses in the CD booklet.

There's a more significant change too, where 'this matter of existence, our ship

wasn't built to last' becomes 'this matter of resistance, our ship was

built to last': perhaps singability trumped significance when these words made

it from the page into the recording studio; or perhaps, as Keith now suspects,

there was a typo in Charnel House's printed edition. The 2008 release is, of course, a

different recording from the one issued on Waite's 1995 album, Temple Bar:

none of the music on The Common Thread has been officially heard before. The

1995 recording was

rather heavier, with piano and a more prominent guitar part weaving around the

voice. The new version is a very radio-friendly track:

lead guitar rides over strummed acoustics, and bass and drums give a strong

forward impetus: the harmonies are slightly Procolesque as the bassline rides up

through the chord-inversions into a very hummable and powerful chorus. There's much here

to please any Procol fan: 'we're sailing out on troubled seas: nail our colours to the mast'

as well as the existential content, as 'life's certainties slip

away' and we finally 'lie down in God's shadow'. The current version is dedicated to

Frankie LaRocka, the

New York A&R man who is also name-checked on The Prodigal Stranger liner-note:

as John Waite's drummer, he introduced Reid to the musicians who wrote this song

(Waite is British by birth, but has lived in the USA for many years). It would

be nice to know exactly who plays in the band but, as with all subsequent

pieces, these details are omitted: 'Played arranged and produced by ...

' is the formula for every track, and the names following are usually those of

the composers and Reid himself. This throws the emphasis squarely on the singing

and the writing, which is evidently the compilers' intention.

The second offering is the 'original version'

of

You're the Voice, Reid's other number one

record (so far!), sung by its co-composer Chris Thompson, of Manfred Mann's

Earthband fame. John Farnham's chart-topping version clearly followed this

prototype very closely, though it dropped a whole tone, into F major, perhaps to allow him

easier access to the falsetto notes that Chris Thompson finds so effortlessly here.

This 1980s recording has a bit of period synth-percussion, yet the album is so

well-mastered – by Fred Kevorkian, known for work with Ryan

Adams, Willie Nelson, The White Stripes, Dave Matthews Band, Iggy Pop a.o. –

that the tracks' very diverse origins do not impinge on the ear at all.

It's otherwise a good deal less poppy, more demanding, than

the famous version with its compressed piano and its skirling bagpipe break. In

particular, Chris Thompson's version uses a pedal bass note in the chorus,

whereas Farnham's bassist followed the chord-changes. Thompson's bassist gets a

good break towards the end of the song, though; elsewhere there's a sax tootling

away that spawned no equivalent in the Farnham version. Lyrically this track is very

assertive and inclusive: we share 'the power to be powerful' and we

can 'write what we wanna write'; but it is also somewhat generic, in that the

exact cause for the fighting is not specified. 'We have a chance to turn the

pages over' suggests a clean start, a wish to close the book on a period of

gun-dominated history: Procol-lovers will note a kinship of imagery with (You

Can't) Turn Back the Page. Unlike many of the pieces on this album, Keith wrote

the words to an existing melodic outline provided by Chris Thompson.

The two men got

to know each other after meeting at a studio: Chris is of course the co-composer of a

Procol tune, The Hand that Rocks the Cradle. How ironic that Thompson's

Voice was not released on the solo-album he was then working on, since his

producers didn't see its commercial potential: yet the song achieved world-wide

fame, and has since been

covered by artists as diverse as Alan Parsons, Barbara Dickson, John Miles and

Brenda Cochrane.

The second offering is the 'original version'

of

You're the Voice, Reid's other number one

record (so far!), sung by its co-composer Chris Thompson, of Manfred Mann's

Earthband fame. John Farnham's chart-topping version clearly followed this

prototype very closely, though it dropped a whole tone, into F major, perhaps to allow him

easier access to the falsetto notes that Chris Thompson finds so effortlessly here.

This 1980s recording has a bit of period synth-percussion, yet the album is so

well-mastered – by Fred Kevorkian, known for work with Ryan

Adams, Willie Nelson, The White Stripes, Dave Matthews Band, Iggy Pop a.o. –

that the tracks' very diverse origins do not impinge on the ear at all.

It's otherwise a good deal less poppy, more demanding, than

the famous version with its compressed piano and its skirling bagpipe break. In

particular, Chris Thompson's version uses a pedal bass note in the chorus,

whereas Farnham's bassist followed the chord-changes. Thompson's bassist gets a

good break towards the end of the song, though; elsewhere there's a sax tootling

away that spawned no equivalent in the Farnham version. Lyrically this track is very

assertive and inclusive: we share 'the power to be powerful' and we

can 'write what we wanna write'; but it is also somewhat generic, in that the

exact cause for the fighting is not specified. 'We have a chance to turn the

pages over' suggests a clean start, a wish to close the book on a period of

gun-dominated history: Procol-lovers will note a kinship of imagery with (You

Can't) Turn Back the Page. Unlike many of the pieces on this album, Keith wrote

the words to an existing melodic outline provided by Chris Thompson.

The two men got

to know each other after meeting at a studio: Chris is of course the co-composer of a

Procol tune, The Hand that Rocks the Cradle. How ironic that Thompson's

Voice was not released on the solo-album he was then working on, since his

producers didn't see its commercial potential: yet the song achieved world-wide

fame, and has since been

covered by artists as diverse as Alan Parsons, Barbara Dickson, John Miles and

Brenda Cochrane.

The music takes a sparser turn for the minor-key

The Heartbreak House, sung and

composed by Michael Saxell. Saxell is Swedish, but no trace of

this shows in his voice: he's entirely at home in the lingua franca of

male rock styling. There's a tinge of Dylan in the world-weary vocal of this anti-military ditty, which

is also played with a slightly Dylanesque feel, Oh Mercy-period guitar jangling and up-front

drums, and plenty of dynamic contrast following the story. A nameless

woman has fallen for a military man, and pays the inevitable price:

lyrically there are some predictable moments, but they're easy to

overlook amid arcane images like growing cobwebs and aching floorboards

(presumably in the latter case there is a pun, conscious or otherwise, on the

word 'pine'). At 3:18 this is the shortest track on the album, and it's

very catchy. How did Reid team up with Saxell? Almost unbelievably, he was

head-hunted by an intermediary in a telephone call that began, 'My name

is Ingmar Bergman, and I'm a great admirer of your work ...'. Keith

relates that he responded by saying that he was a great admirer of

Bergman's work ... but it turned out to be a different Bergman! Reid's American connections

can be heard in the sound-world presented here: Saxell originally recorded just guitar and voice, in Sweden: Keith saw

the piece rather differently and took it to upstate New York where the

additional instruments were added, and where it was mixed. It's by no

means the only track on the album to have covered a lot of ground during

its gestation.

The music takes a sparser turn for the minor-key

The Heartbreak House, sung and

composed by Michael Saxell. Saxell is Swedish, but no trace of

this shows in his voice: he's entirely at home in the lingua franca of

male rock styling. There's a tinge of Dylan in the world-weary vocal of this anti-military ditty, which

is also played with a slightly Dylanesque feel, Oh Mercy-period guitar jangling and up-front

drums, and plenty of dynamic contrast following the story. A nameless

woman has fallen for a military man, and pays the inevitable price:

lyrically there are some predictable moments, but they're easy to

overlook amid arcane images like growing cobwebs and aching floorboards

(presumably in the latter case there is a pun, conscious or otherwise, on the

word 'pine'). At 3:18 this is the shortest track on the album, and it's

very catchy. How did Reid team up with Saxell? Almost unbelievably, he was

head-hunted by an intermediary in a telephone call that began, 'My name

is Ingmar Bergman, and I'm a great admirer of your work ...'. Keith

relates that he responded by saying that he was a great admirer of

Bergman's work ... but it turned out to be a different Bergman! Reid's American connections

can be heard in the sound-world presented here: Saxell originally recorded just guitar and voice, in Sweden: Keith saw

the piece rather differently and took it to upstate New York where the

additional instruments were added, and where it was mixed. It's by no

means the only track on the album to have covered a lot of ground during

its gestation.

A Common Thread

is another lyric encountered in the

My

Own Choice collection, although there it is called 'The Common

Thread' like the present CD album.

Southside Johnny

gives a stirring account of Reid's words, making no changes bar the

addition of a soulful 'Yes it does' (which is bracketed in the CD's lyric

booklet). Here again we encounter the idea that 'there's a voice ...

that belongs to all of us', somehow a far cry from the frequently

alienated world of early-period Reid (but never fear: we haven't got to

the monkey song yet!). A Common Thread starts, as Reid is wont to

do, by capturing the listener with a well-known phrase – 'hearts of oak'

– which he mutates later to 'hearts of gold' – while cataloguing the

earthy artisan virtues that hold our lives together, and contrasting

them with the (literally, middle-class) activities of those 'just busy making deals'. The rueful

moral seems to be that physical work is 'a story that everybody needs, but nobody

heeds'. The 'thread' image is skilfully exploited for a double meaning,

signifying a unifying theme as well an item of haberdashery: the whole piece works extremely well.

Thread is the first song on the album whose instrumentation is

thoroughly Procolesque: piano, Hammond, guitar, bass and drums introduce

a chord sequence (the music is by Procol collaborator Matt Noble) that

echoes Air on a G String, albeit in A major. Although space

constraints again

preclude a full who-did-what, the brass arranger, keyboardist

Barry Goldberg,

does get an individual – and well-deserved – credit. This is a big,

mellow ballad, the sort that Joe Cocker has made his own: it would be a

pleasure to hear those tonsils wrapped around this piece, perhaps earning Reid some more of the contemporary exposure he so obviously

merits. Yet Southside Johnny's performance is excellent, and highlights

one of the major selling-points of this album: it contains a profusion

of strikingly good singers. Perhaps nobody matches the poignant clarity and

drama of Gary Brooker's delivery, but undoubtedly nobody is trying to –

quite rightly so. There

are several songs here, however, that it would be good to hear Brooker tackle. We might wonder if any of these

words are lingering, unset, in

the large album of Reid lyrics to which Brooker turns when writing new

material;

but my understanding is that Keith doesn't typically like to send the same lyric out

to more than one composer, and the instances (Into the Flood, Victims

of the Fury) where different Trower and Brooker settings are extant

have come about only because Gary had sat on the words so long

that they were offered afresh and in good faith to Robin, whose versions didn't come to

Brooker's notice until after his own composing was done.

A Common Thread

is another lyric encountered in the

My

Own Choice collection, although there it is called 'The Common

Thread' like the present CD album.

Southside Johnny

gives a stirring account of Reid's words, making no changes bar the

addition of a soulful 'Yes it does' (which is bracketed in the CD's lyric

booklet). Here again we encounter the idea that 'there's a voice ...

that belongs to all of us', somehow a far cry from the frequently

alienated world of early-period Reid (but never fear: we haven't got to

the monkey song yet!). A Common Thread starts, as Reid is wont to

do, by capturing the listener with a well-known phrase – 'hearts of oak'

– which he mutates later to 'hearts of gold' – while cataloguing the

earthy artisan virtues that hold our lives together, and contrasting

them with the (literally, middle-class) activities of those 'just busy making deals'. The rueful

moral seems to be that physical work is 'a story that everybody needs, but nobody

heeds'. The 'thread' image is skilfully exploited for a double meaning,

signifying a unifying theme as well an item of haberdashery: the whole piece works extremely well.

Thread is the first song on the album whose instrumentation is

thoroughly Procolesque: piano, Hammond, guitar, bass and drums introduce

a chord sequence (the music is by Procol collaborator Matt Noble) that

echoes Air on a G String, albeit in A major. Although space

constraints again

preclude a full who-did-what, the brass arranger, keyboardist

Barry Goldberg,

does get an individual – and well-deserved – credit. This is a big,

mellow ballad, the sort that Joe Cocker has made his own: it would be a

pleasure to hear those tonsils wrapped around this piece, perhaps earning Reid some more of the contemporary exposure he so obviously

merits. Yet Southside Johnny's performance is excellent, and highlights

one of the major selling-points of this album: it contains a profusion

of strikingly good singers. Perhaps nobody matches the poignant clarity and

drama of Gary Brooker's delivery, but undoubtedly nobody is trying to –

quite rightly so. There

are several songs here, however, that it would be good to hear Brooker tackle. We might wonder if any of these

words are lingering, unset, in

the large album of Reid lyrics to which Brooker turns when writing new

material;

but my understanding is that Keith doesn't typically like to send the same lyric out

to more than one composer, and the instances (Into the Flood, Victims

of the Fury) where different Trower and Brooker settings are extant

have come about only because Gary had sat on the words so long

that they were offered afresh and in good faith to Robin, whose versions didn't come to

Brooker's notice until after his own composing was done.

Next, a song about a graveyard. Potters Field is

a generic name for

strangers' burial-grounds, but after name-checking Judas and 'his Lord' Reid

focuses on the weed-choked Potters Field on Hart Island, off Long Island Sound,

the largest cemetery in the USA: it's one of

several songs on the album to centre upon a particular place, real or otherwise.

The lyric deals with two inhabitants of this graveyard, one 'refugee from a

far-off land' whose 'dreams were bought and sold'; the other a young woman

who turns to selling herself to fuel a drug habit and 'got too high, or maybe

she forgot to fly'. There is a kind of melancholy word-play in 'they laid her

low', as the burials are described, and some real Liquorice John imagery

in 'she hit the ground in Potters Field' (the placename no more needs an

apostrophe than Shepherds Bush does, by the way). So far, so Procoloid: but the mood here

is tinged with folk, as the track starts with just two steel-strung guitars,

finger-picked with plenty of fret-squeak, later joined by unobtrusive bass:

Bernie Shanahan sings this

plaintive piece (composed by Michael Saxell) with great feeling: the album is on the whole very much a

sung sequence, with relatively-few featured instrumental passages. Latterly

the choruses feature multi-tracked vocals, and it's easy to imagine this song

being performed in a folk-club, extracting maximum effect from a minimum of

technical resources.

Next, a song about a graveyard. Potters Field is

a generic name for

strangers' burial-grounds, but after name-checking Judas and 'his Lord' Reid

focuses on the weed-choked Potters Field on Hart Island, off Long Island Sound,

the largest cemetery in the USA: it's one of

several songs on the album to centre upon a particular place, real or otherwise.

The lyric deals with two inhabitants of this graveyard, one 'refugee from a

far-off land' whose 'dreams were bought and sold'; the other a young woman

who turns to selling herself to fuel a drug habit and 'got too high, or maybe

she forgot to fly'. There is a kind of melancholy word-play in 'they laid her

low', as the burials are described, and some real Liquorice John imagery

in 'she hit the ground in Potters Field' (the placename no more needs an

apostrophe than Shepherds Bush does, by the way). So far, so Procoloid: but the mood here

is tinged with folk, as the track starts with just two steel-strung guitars,

finger-picked with plenty of fret-squeak, later joined by unobtrusive bass:

Bernie Shanahan sings this

plaintive piece (composed by Michael Saxell) with great feeling: the album is on the whole very much a

sung sequence, with relatively-few featured instrumental passages. Latterly

the choruses feature multi-tracked vocals, and it's easy to imagine this song

being performed in a folk-club, extracting maximum effect from a minimum of

technical resources.

On the other hand the instrumental playing on

Gold Fever

is unmissable, showily virtuosic. Co-composer

Jeff Golub sounds

like Manitas de Plata as his flamenco guitar scampers all over this

hectic, Latino-oriented offering. On one level it harks back to the

Californian gold-rush,

but the imagery resonates more with contemporary life in LA's Tinseltown:

the male character has a script under consideration, but isn't

considered bankable: he's known the high life, having made some money

'before the boom went splash' (classic Reid catachresis here!), but now turns,

like the girl in

the previous song, to 'a silver spoon' – ironically divorced from its

usual, upbeat metaphorical meaning. In its treatment of betrayal, the song

carries a hint of the world of Wall

Street Blues. It's not quite clear to me how the first verse relates

to the rest of this song: it begins with 'a struggle on the

causeway' and a lapse 'of sacred trust'. But this non-linearity isn't a defect for

the Procol fan: after 38 years of listening I still can't get Whaling

Stories to come into focus fully and I'm sure it's not meant to.

Musically, this track is a highlight: John Waite's delivery is terrific

– again, more than a hint of Dylan,

Blood on the Tracks period perhaps – and the slightly astringent

relation of the tune to the chordal accompaniment is deliciously

haunting. Insistent handclaps complete the Hispanic soundworld.

Memo to self: listen to more Waite. Intriguingly, considering the fact that Reid's songwriting life has been

divided between Britain and the USA, the lyric booklet uses the

transAtlantic 'honor' alongside the native 'jewellery': what are we to

make of this!

On the other hand the instrumental playing on

Gold Fever

is unmissable, showily virtuosic. Co-composer

Jeff Golub sounds

like Manitas de Plata as his flamenco guitar scampers all over this

hectic, Latino-oriented offering. On one level it harks back to the

Californian gold-rush,

but the imagery resonates more with contemporary life in LA's Tinseltown:

the male character has a script under consideration, but isn't

considered bankable: he's known the high life, having made some money

'before the boom went splash' (classic Reid catachresis here!), but now turns,

like the girl in

the previous song, to 'a silver spoon' – ironically divorced from its

usual, upbeat metaphorical meaning. In its treatment of betrayal, the song

carries a hint of the world of Wall

Street Blues. It's not quite clear to me how the first verse relates

to the rest of this song: it begins with 'a struggle on the

causeway' and a lapse 'of sacred trust'. But this non-linearity isn't a defect for

the Procol fan: after 38 years of listening I still can't get Whaling

Stories to come into focus fully and I'm sure it's not meant to.

Musically, this track is a highlight: John Waite's delivery is terrific

– again, more than a hint of Dylan,

Blood on the Tracks period perhaps – and the slightly astringent

relation of the tune to the chordal accompaniment is deliciously

haunting. Insistent handclaps complete the Hispanic soundworld.

Memo to self: listen to more Waite. Intriguingly, considering the fact that Reid's songwriting life has been

divided between Britain and the USA, the lyric booklet uses the

transAtlantic 'honor' alongside the native 'jewellery': what are we to

make of this!

A

glance at the mere track-listing might suggest that Venus

Exploding would be a comic song involving iconic statuary

and gelignite, but that's far from the case: the Venus in

question is the planet, and the context is cataclysmic. The night sky is on fire, the stars fall down, yet

it starts gently, in a far-away, melodic mood, like an offering

from The Prodigal

Stranger, and has similar compound-time feel to Perpetual Motion.

Composer Matt Noble, of course, is credited as a co-author of that late Procol

track, and this is the song that most-closely approximates to

the Harum sound-world: piano-chords alternate over a held bass

note, heavy guitar emphasises the movement of the bassline when

it eventually detaches itself from root position. The grandiloquent

drums also recall the dramatic punctuations of BJ Wilson, but

here they are heavily-processed, so the instrumental track doesn't entirely

sound like a live band, but rather diverts the mind's ear to the

multi-track studio. The song slows to a definite, stately

conclusion, yet guitar and piano play on, momentarily, into an

unexpected semi-fade. The words involve searching for some meaning

when 'the signs were deceiving'. An eerie atmosphere prevails,

though latter-day Reid is more wont to spell it out ('a strange

misty haze') than in former, more allusive times. Nevertheless

lines like 'lost in the mirror' take us through The Hand that

Rocks the Cradle right back to the days

of A Whiter Shade of Pale, and there is a fascinating

instance of Thomas Hardy-style 'cunning irregularity' in

that 'tossed between dreams and awakening', in the first verse,

mutates to 'lost between truth and awakening' in the second.

Similarly the opening chorus is first-person past-tense, the

closing one second-person future. Bernie Shanahan's performance is strong,

his voice warm, but

arguably he is fulfilling the role of identikit rock balladeer, rather than that

of an alienated visionary searching for meaning (the soaring guitar

solo is similarly generic). I found him more affecting on Potters Field,

but this is still an excellent track, whose haunting, hymn-like

chorus sticks deliciously in the mind, with the utter simplicity

of a classic.

A

glance at the mere track-listing might suggest that Venus

Exploding would be a comic song involving iconic statuary

and gelignite, but that's far from the case: the Venus in

question is the planet, and the context is cataclysmic. The night sky is on fire, the stars fall down, yet

it starts gently, in a far-away, melodic mood, like an offering

from The Prodigal

Stranger, and has similar compound-time feel to Perpetual Motion.

Composer Matt Noble, of course, is credited as a co-author of that late Procol

track, and this is the song that most-closely approximates to

the Harum sound-world: piano-chords alternate over a held bass

note, heavy guitar emphasises the movement of the bassline when

it eventually detaches itself from root position. The grandiloquent

drums also recall the dramatic punctuations of BJ Wilson, but

here they are heavily-processed, so the instrumental track doesn't entirely

sound like a live band, but rather diverts the mind's ear to the

multi-track studio. The song slows to a definite, stately

conclusion, yet guitar and piano play on, momentarily, into an

unexpected semi-fade. The words involve searching for some meaning

when 'the signs were deceiving'. An eerie atmosphere prevails,

though latter-day Reid is more wont to spell it out ('a strange

misty haze') than in former, more allusive times. Nevertheless

lines like 'lost in the mirror' take us through The Hand that

Rocks the Cradle right back to the days

of A Whiter Shade of Pale, and there is a fascinating

instance of Thomas Hardy-style 'cunning irregularity' in

that 'tossed between dreams and awakening', in the first verse,

mutates to 'lost between truth and awakening' in the second.

Similarly the opening chorus is first-person past-tense, the

closing one second-person future. Bernie Shanahan's performance is strong,

his voice warm, but

arguably he is fulfilling the role of identikit rock balladeer, rather than that

of an alienated visionary searching for meaning (the soaring guitar

solo is similarly generic). I found him more affecting on Potters Field,

but this is still an excellent track, whose haunting, hymn-like

chorus sticks deliciously in the mind, with the utter simplicity

of a classic.

The Only Monkey is the album's most recently-recorded track. It's a

stingingly satirical swipe at homo sapiens, mordant, insistent, and

bleakly hilarious. 'The human is a monkey with a diseased brain' (later 'heart',

latterly 'soul') in Reid's vision: he 'makes killing a game', 'takes pleasure

from pain', 'blows things apart', and – uniquely in the animal world – he 'needs

things to do' and is 'in search of a goal'. The middle-eight section runs, 'he'll

sell his own soul for a gallon of gas' (not 'petrol' as it's known in the UK!),

'turn trees into paper to wipe his own ass'. This sort of scathing wit is worth

reams of pious eco-cant, and it is brilliantly set to music by a collaborator

Reid has long admired, the marvellous

Chaz Jankel, who is still

touring with The Blockheads, and must have welcomed the chance to work with a

lyric on a par with the late Ian Dury's best inspirations. Biological pedants will flinch at the

category error in 'from the mightiest ape to the tiny boll weevil, the only

monkey that you can call evil' but in fact this literal inaccuracy only adds to

the fun: likewise, the way the savagery of the verses, whose key-word is

'diseased', gives over to a playground-taunting chorus where the central notion

is the weedily-repeated 'silly'. No stranger to the top of the charts, Jankel has come up with an catchy, unpretentious, danceable ditty:

he hits us with his rhythm stick, as it were, with steady drumming, offbeat guitaring, and plonking wah-wah clavinet. What sounds

simple is kept interesting with subtle variations, such as a thread of backward guitar, some Beatlish arpeggiations,

foolish toy-noises, and a cracking solo guitar break.

A repeated and highly unconventional jump-cut from G minor to A flat major and back adds

a Squeeze-like freshness and

individuality. BtP asked Keith Reid if he could be heard anywhere on the album,

and he conceded that he was audible, but declined to be specific: my guess is

that his voice is involved in the amusingly-distorted call-and-response vocal.

It's all neatly-rhymed, except for 'earth' and 'self', which curiously retreads

the least euphonious couplet in The Emperor's New Clothes: 'You promise

the moon and squander the earth / The only person you fool is yourself'. If I

had my pick The Only Monkey would be the single from the album: punchy,

pointed, modern in sound, and full of provoking soundbites: 'the

human is the monkey who invented the Zoo ...' (I wonder if the capital letter in

the lyric-booklet harks back to Procol's briefly-supportive 1990s record-label?)

The Only Monkey is the album's most recently-recorded track. It's a

stingingly satirical swipe at homo sapiens, mordant, insistent, and

bleakly hilarious. 'The human is a monkey with a diseased brain' (later 'heart',

latterly 'soul') in Reid's vision: he 'makes killing a game', 'takes pleasure

from pain', 'blows things apart', and – uniquely in the animal world – he 'needs

things to do' and is 'in search of a goal'. The middle-eight section runs, 'he'll

sell his own soul for a gallon of gas' (not 'petrol' as it's known in the UK!),

'turn trees into paper to wipe his own ass'. This sort of scathing wit is worth

reams of pious eco-cant, and it is brilliantly set to music by a collaborator

Reid has long admired, the marvellous

Chaz Jankel, who is still

touring with The Blockheads, and must have welcomed the chance to work with a

lyric on a par with the late Ian Dury's best inspirations. Biological pedants will flinch at the

category error in 'from the mightiest ape to the tiny boll weevil, the only

monkey that you can call evil' but in fact this literal inaccuracy only adds to

the fun: likewise, the way the savagery of the verses, whose key-word is

'diseased', gives over to a playground-taunting chorus where the central notion

is the weedily-repeated 'silly'. No stranger to the top of the charts, Jankel has come up with an catchy, unpretentious, danceable ditty:

he hits us with his rhythm stick, as it were, with steady drumming, offbeat guitaring, and plonking wah-wah clavinet. What sounds

simple is kept interesting with subtle variations, such as a thread of backward guitar, some Beatlish arpeggiations,

foolish toy-noises, and a cracking solo guitar break.

A repeated and highly unconventional jump-cut from G minor to A flat major and back adds

a Squeeze-like freshness and

individuality. BtP asked Keith Reid if he could be heard anywhere on the album,

and he conceded that he was audible, but declined to be specific: my guess is

that his voice is involved in the amusingly-distorted call-and-response vocal.

It's all neatly-rhymed, except for 'earth' and 'self', which curiously retreads

the least euphonious couplet in The Emperor's New Clothes: 'You promise

the moon and squander the earth / The only person you fool is yourself'. If I

had my pick The Only Monkey would be the single from the album: punchy,

pointed, modern in sound, and full of provoking soundbites: 'the

human is the monkey who invented the Zoo ...' (I wonder if the capital letter in

the lyric-booklet harks back to Procol's briefly-supportive 1990s record-label?)

A diametrical shift of emphasis brings us to a big ballad,

It Might Be Your Heart,

sung by Chris Thompson, who wrote the music with keyboardist Mark Taylor. Procol-fanciers will be immediately struck by the featured phrase

'too much between us' in the chorus: in 1969 this was the enigmatic title of

Procol's tenderest piece to date, depicting lovers separated by the Atlantic,

and where 'between us' compendiously signified – and emphasised the

incompatibility of – simultaneous separation and mutual affection. That early song left

everything to the imagination: in Blakean terms, it was born of innocence rather

than experience. It's no surprise that, so many years later, Reid now writes

more from the latter point-of-view. This is presumably what people call 'AOR' – it lacks the Juvenile-Oriented Rock elements that made the

Monkey track such fun

– as it poses the middle-aged question of how 'a lifetime of growing together'

can be 'over so fast'. The lyric is not afraid to preach ('if you take love for

granted then love disappears') nor does it shy away from the stock-in-trade dependables of 'your whole world falls down / and skies full of dreams / come

crashing to the ground'. No doubt there is a big market for this kind of work,

and no doubt this is a satisfyingly well-done example of its kind: but it did not chime with this particular reviewer greatly, though the melody

is catchy enough. 'What can I do / With this space between me and you', Thompson emotes

authentically over piano, organ, bass and drums, with guitar offbeat clipping:

midway it grows orchestration and female backing-voices. Despite a similarity to

Crucifiction Lane in terms of tempo, this is nothing like Procol Harum music,

and it's as

well to remember that the album is not specifically aimed at fans of that band.

For all I know this is the piece of The Common Thread that will get the most air-play, or attract

the most cover-versions. Reid mentioned in conversation that 'It will be

interesting to know if [the BtP public] think any of this is like Procol Harum'

but added that 'I don't write Procol Harum words specifically'. As a working

songwriter, compiling a sampler CD of 'words I'm really proud of', he is

showing a full, and enviable, range on this recording.

A diametrical shift of emphasis brings us to a big ballad,

It Might Be Your Heart,

sung by Chris Thompson, who wrote the music with keyboardist Mark Taylor. Procol-fanciers will be immediately struck by the featured phrase

'too much between us' in the chorus: in 1969 this was the enigmatic title of

Procol's tenderest piece to date, depicting lovers separated by the Atlantic,

and where 'between us' compendiously signified – and emphasised the

incompatibility of – simultaneous separation and mutual affection. That early song left

everything to the imagination: in Blakean terms, it was born of innocence rather

than experience. It's no surprise that, so many years later, Reid now writes

more from the latter point-of-view. This is presumably what people call 'AOR' – it lacks the Juvenile-Oriented Rock elements that made the

Monkey track such fun

– as it poses the middle-aged question of how 'a lifetime of growing together'

can be 'over so fast'. The lyric is not afraid to preach ('if you take love for

granted then love disappears') nor does it shy away from the stock-in-trade dependables of 'your whole world falls down / and skies full of dreams / come

crashing to the ground'. No doubt there is a big market for this kind of work,

and no doubt this is a satisfyingly well-done example of its kind: but it did not chime with this particular reviewer greatly, though the melody

is catchy enough. 'What can I do / With this space between me and you', Thompson emotes

authentically over piano, organ, bass and drums, with guitar offbeat clipping:

midway it grows orchestration and female backing-voices. Despite a similarity to

Crucifiction Lane in terms of tempo, this is nothing like Procol Harum music,

and it's as

well to remember that the album is not specifically aimed at fans of that band.

For all I know this is the piece of The Common Thread that will get the most air-play, or attract

the most cover-versions. Reid mentioned in conversation that 'It will be

interesting to know if [the BtP public] think any of this is like Procol Harum'

but added that 'I don't write Procol Harum words specifically'. As a working

songwriter, compiling a sampler CD of 'words I'm really proud of', he is

showing a full, and enviable, range on this recording.

Silver Town, sung by

Steve Booker, is a delectable number with a folkish feel. The British

songwriter-producer's own MySpace bills him as 'Pop/Acoustic/Soul', and he's best-known as

the author of Duffy's massive 2008 summer hit, Mercy, currently topping the 1.5m sales mark. Reid and Booker were put in

touch by publishers, maybe by Simon Platz, who is credited in the CD

booklet for 'taking care of business': yet Steve's roster of

collaborations,

here, rather curiously doesn't include either of the Booker/Reid

(!) songs on this album. He has a very agreeable, carefully-controlled

voice, bereft of posturing. The chorus is delightful, strongly haunting

(incidentally, it shares its IV-V-I harmonies with the similarly-strong

refrain to Venus Exploding): this is another piece one could

imagine sung by massed voices in a folk-club setting. Interviewed

earlier this year for

The Argotist,

Reid divulged ' ... my definition of a great

song would be something that can be put across with very limited

instrumentation ... it's all the devices of rhyming schemes, hooks,

choruses etc. that contribute to making a song memorable ... if you've just got a guitar and a voice your

song has to be special in order to survive.' This poignant narrative

song is certainly a survivor. The opening line, 'This town's been blown away', immediately calls to mind London's disastrous

Silvertown explosion

in 1917, yet the repeated allusions to 'Washington' show that once

again the setting is not British but American. Yet this Silver Town is

an imaginary place, intended to symbolise any small community ('built

from a grain of sand') whose fate is dependent on a remote government.

'It's talking about the relationship between big business and

administration,' Keith told BtP. The contrast between this fictional

place and Cerdes (Outside the Gates of) neatly epitomises

another

transition in Reid's songwriting over forty years, from 1967's

disturbing, surreal fancies to today's topical, politically-pointed

narratives. There is, it seems, a humorous

reference, a pun, somewhere in this lyric, and Keith thinks BtP should offer a

prize to the first reader to

write in explaining it. I confess that it eludes this reviewer,

though there is nonetheless plenty of felicitous wordplay: 'blew (?blue)

us out of the sky', 'though the money's all run out / there's a wealth

of folk', 'When they turned up the heat in Washington / they left us out

in the cold'. Skilfully painting the small-town scene, in few words,

Reid evokes the railway and the church: 'the wheels still turn ... the

bells ring out of time'. The song asks 'Has the Lord passed us by?', and

it's not the only instance of Christian imagery in this collection:

Potters Field quotes seven words verbatim

from the King James Bible (curiously Judas's reward

was pieces of silver, a word heard relatively often on the

album), Too Close to Call speaks of 'praying to the Lord', and the

spirituality of the God's Shadow lyric is enhanced by its

dedication to the late LaRocka,

who 'lies in God's Shadow now'.

Silver Town, sung by

Steve Booker, is a delectable number with a folkish feel. The British

songwriter-producer's own MySpace bills him as 'Pop/Acoustic/Soul', and he's best-known as

the author of Duffy's massive 2008 summer hit, Mercy, currently topping the 1.5m sales mark. Reid and Booker were put in

touch by publishers, maybe by Simon Platz, who is credited in the CD

booklet for 'taking care of business': yet Steve's roster of

collaborations,

here, rather curiously doesn't include either of the Booker/Reid

(!) songs on this album. He has a very agreeable, carefully-controlled

voice, bereft of posturing. The chorus is delightful, strongly haunting

(incidentally, it shares its IV-V-I harmonies with the similarly-strong

refrain to Venus Exploding): this is another piece one could

imagine sung by massed voices in a folk-club setting. Interviewed

earlier this year for

The Argotist,

Reid divulged ' ... my definition of a great

song would be something that can be put across with very limited

instrumentation ... it's all the devices of rhyming schemes, hooks,

choruses etc. that contribute to making a song memorable ... if you've just got a guitar and a voice your

song has to be special in order to survive.' This poignant narrative

song is certainly a survivor. The opening line, 'This town's been blown away', immediately calls to mind London's disastrous

Silvertown explosion

in 1917, yet the repeated allusions to 'Washington' show that once

again the setting is not British but American. Yet this Silver Town is

an imaginary place, intended to symbolise any small community ('built

from a grain of sand') whose fate is dependent on a remote government.

'It's talking about the relationship between big business and

administration,' Keith told BtP. The contrast between this fictional

place and Cerdes (Outside the Gates of) neatly epitomises

another

transition in Reid's songwriting over forty years, from 1967's

disturbing, surreal fancies to today's topical, politically-pointed

narratives. There is, it seems, a humorous

reference, a pun, somewhere in this lyric, and Keith thinks BtP should offer a

prize to the first reader to

write in explaining it. I confess that it eludes this reviewer,

though there is nonetheless plenty of felicitous wordplay: 'blew (?blue)

us out of the sky', 'though the money's all run out / there's a wealth

of folk', 'When they turned up the heat in Washington / they left us out

in the cold'. Skilfully painting the small-town scene, in few words,

Reid evokes the railway and the church: 'the wheels still turn ... the

bells ring out of time'. The song asks 'Has the Lord passed us by?', and

it's not the only instance of Christian imagery in this collection:

Potters Field quotes seven words verbatim

from the King James Bible (curiously Judas's reward

was pieces of silver, a word heard relatively often on the

album), Too Close to Call speaks of 'praying to the Lord', and the

spirituality of the God's Shadow lyric is enhanced by its

dedication to the late LaRocka,

who 'lies in God's Shadow now'.

Ninety-Nine Degrees in the Shade,

sung by Southside Johnny,

is the least polite song on the album, in that it sounds as if it's come

direct from a stage somewhere, rather than having its origins in a studio: it's

also less sophisticated in structure than most of the other

pieces, in that it is untroubled by a middle-eight. It's a

medium-paced, sleazy rock number, composition credited to John Lyon

(who probably wasn't 'Southside' to his mother). It would be

good to know

who is playing this nice dirty guitar – it sounds so live that there is

even a glitch (1:38) in the stereo image – and the fluent bass

and the wallopingly syncopated drums. These are the only musical

resources, save a second guitar part and a maraca or two. The

words are witty and unexpected ('hear that asphalt bubble' for

instance): the first and third verses in particular are just

perfect of their kind, as the 'hurricane' woman on her Harley

blows into town where Southside is 'selling sneakers' or

'working in a bar', until some astrological hokum (she calls it

'astronomy') leads to their brief conjunction, and suddenly

we're watching 'her tail-lights fade'. Southside Johnny's

delivery brilliantly combines gruff machismo with an

acknowledgement of defeat by an elemental force; his extemporising

in the playout (noted

here) is

great fun too. Top marks for this track ... though we have heard

it before: Keith Reid didn't know it until after the tracklist was finalised,

but Southside Johnny released this track in a 'not authorised'

form, on a gigs-only CD, a few years ago.

Ninety-Nine Degrees in the Shade,

sung by Southside Johnny,

is the least polite song on the album, in that it sounds as if it's come

direct from a stage somewhere, rather than having its origins in a studio: it's

also less sophisticated in structure than most of the other

pieces, in that it is untroubled by a middle-eight. It's a

medium-paced, sleazy rock number, composition credited to John Lyon

(who probably wasn't 'Southside' to his mother). It would be

good to know

who is playing this nice dirty guitar – it sounds so live that there is

even a glitch (1:38) in the stereo image – and the fluent bass

and the wallopingly syncopated drums. These are the only musical

resources, save a second guitar part and a maraca or two. The

words are witty and unexpected ('hear that asphalt bubble' for

instance): the first and third verses in particular are just

perfect of their kind, as the 'hurricane' woman on her Harley

blows into town where Southside is 'selling sneakers' or

'working in a bar', until some astrological hokum (she calls it

'astronomy') leads to their brief conjunction, and suddenly

we're watching 'her tail-lights fade'. Southside Johnny's

delivery brilliantly combines gruff machismo with an

acknowledgement of defeat by an elemental force; his extemporising

in the playout (noted

here) is

great fun too. Top marks for this track ... though we have heard

it before: Keith Reid didn't know it until after the tracklist was finalised,

but Southside Johnny released this track in a 'not authorised'

form, on a gigs-only CD, a few years ago.

The

legendary Terry Reid has a hard act to follow, as the running-order has panned

out. Too Close to Call is a night-time FM radio-oriented piece, and his

striking voice, with its haunting falsettos, is ghosted by a female vocalist –

almost inaudible at times – to very interesting effect. The music is credited to

Barry Goldberg (Electric Flag, anybody?), who was responsible for reintroducing

Reid to Reid: the Terry Reid Trio (which later included

Pete Solley) had toured with Procol in the earliest days.

To a driving rhythm, with effective brass and reeds here and there, the song

catalogues some 'everyman' activities (with a touch of

Raymond Carver, when the

blue-collar basics of 'walking down the street ... drinking in a bar ... dancing

with your wife' are disturbed by 'howling at the moon'!), then reflects on the

capriciousness of fate. 'It's too early to say / where the pieces will fall ...

it's just a stroke of luck'. It remains ambiguous as to whether good luck or bad

luck is intended: both 'fall' and 'stroke' have fatal connotations. Only the

middle section, 'Happiness is just a state of mind', commits itself to a

definite message; and fans reared on Old Testament Reid will have

to get used to his growing explicitude. This is a solid, likeable piece, yet I

confess that it's the one point on the album where I took my ear

off the ball, as it were. Its hypnotically-unvarying drum part

may be the reason, or maybe it's just the fact that it crops up,

45 minutes in, at some innate threshold of concentration. If so,

shuffle-mode will cure it. The official running-order, however,

was the subject of 'endless rearrangement ... as much effort as

any of the rest of it,' according to Keith, so it would be a

pity to tamper with his programming. I do note,

however, that the last three numbers come close to

violating the Procol principle that guarantees aural freshness by ensuring that

adjacent tracks are not in the same key. Whereas the songs so far have been in

A / G / E minor / A / E minor / A minor / B / G minor / C / F#, the last

three are in E major, E minor and E major again.

The

legendary Terry Reid has a hard act to follow, as the running-order has panned

out. Too Close to Call is a night-time FM radio-oriented piece, and his

striking voice, with its haunting falsettos, is ghosted by a female vocalist –

almost inaudible at times – to very interesting effect. The music is credited to

Barry Goldberg (Electric Flag, anybody?), who was responsible for reintroducing

Reid to Reid: the Terry Reid Trio (which later included

Pete Solley) had toured with Procol in the earliest days.

To a driving rhythm, with effective brass and reeds here and there, the song

catalogues some 'everyman' activities (with a touch of

Raymond Carver, when the

blue-collar basics of 'walking down the street ... drinking in a bar ... dancing

with your wife' are disturbed by 'howling at the moon'!), then reflects on the

capriciousness of fate. 'It's too early to say / where the pieces will fall ...

it's just a stroke of luck'. It remains ambiguous as to whether good luck or bad

luck is intended: both 'fall' and 'stroke' have fatal connotations. Only the

middle section, 'Happiness is just a state of mind', commits itself to a

definite message; and fans reared on Old Testament Reid will have

to get used to his growing explicitude. This is a solid, likeable piece, yet I

confess that it's the one point on the album where I took my ear

off the ball, as it were. Its hypnotically-unvarying drum part

may be the reason, or maybe it's just the fact that it crops up,

45 minutes in, at some innate threshold of concentration. If so,

shuffle-mode will cure it. The official running-order, however,

was the subject of 'endless rearrangement ... as much effort as

any of the rest of it,' according to Keith, so it would be a

pity to tamper with his programming. I do note,

however, that the last three numbers come close to

violating the Procol principle that guarantees aural freshness by ensuring that

adjacent tracks are not in the same key. Whereas the songs so far have been in

A / G / E minor / A / E minor / A minor / B / G minor / C / F#, the last

three are in E major, E minor and E major again.

The artful Steve Booker, however,

starts Right About Now

on the subdominant, which lessens any unwanted sense of tonal

continuity; and he follows this with a plangent guitar discord that sets the

atmosphere well for the album's final, sad story: it might

equally have been titled He's

Leaving Home. Lyrically this is another 'grown-up' item (surely a preferable

term to 'AOR'), and Booker sings his very melodic lines in sincere,

unostentatious fashion. It's loosely built on two meanings of 'right': one

suggesting immediacy, as the abandoned lover finds the letter explaining 'right

about now I'll become a stranger', and one suggesting correctitude: 'so hard to

be right about you'. This is an emotionally-complex offering ('I dried your

tears, tried to make them disappear'), dealing with authentic symptoms of

desperation ('the walls will close in so fast ... you'll wonder if you're gonna

last') but not shying away from endemic Reid wordplay (the 'damn your tears' pun

works only because we have the printed words, and it's worth mentioning that the

typographic layout has been given a lot of interesting thought). Once

again, strummed acoustic guitar is the backbone of this song, though bass and

organ, and harmony voices, make a good solid contribution; drums are effectively

withheld until the halfway mark, there's a hint of accordion, and what sounds

like a left-hand piano note adds dark colour to the instrumental texture.

The artful Steve Booker, however,

starts Right About Now

on the subdominant, which lessens any unwanted sense of tonal

continuity; and he follows this with a plangent guitar discord that sets the

atmosphere well for the album's final, sad story: it might

equally have been titled He's

Leaving Home. Lyrically this is another 'grown-up' item (surely a preferable

term to 'AOR'), and Booker sings his very melodic lines in sincere,

unostentatious fashion. It's loosely built on two meanings of 'right': one

suggesting immediacy, as the abandoned lover finds the letter explaining 'right

about now I'll become a stranger', and one suggesting correctitude: 'so hard to

be right about you'. This is an emotionally-complex offering ('I dried your

tears, tried to make them disappear'), dealing with authentic symptoms of

desperation ('the walls will close in so fast ... you'll wonder if you're gonna

last') but not shying away from endemic Reid wordplay (the 'damn your tears' pun

works only because we have the printed words, and it's worth mentioning that the

typographic layout has been given a lot of interesting thought). Once

again, strummed acoustic guitar is the backbone of this song, though bass and

organ, and harmony voices, make a good solid contribution; drums are effectively

withheld until the halfway mark, there's a hint of accordion, and what sounds

like a left-hand piano note adds dark colour to the instrumental texture.

Finishing in a fade (as more than half the pieces do) this bittersweet

confessional makes an unconventionally downbeat conclusion to the album, but let

us hope it is not the end of this particular thread in Keith Reid's long

involvement in the music business. He mentions that these are by no means the

only songs that he's written with the present collaborators, and that there were

'plenty of other items that might have made the cut'. There was theoretically

room for another five or so songs on the CD but, as Keith says, '55 minutes seems plenty:

sometimes too much is worse

than not enough. These are just music and words that I'd like people to hear.'

Finishing in a fade (as more than half the pieces do) this bittersweet

confessional makes an unconventionally downbeat conclusion to the album, but let

us hope it is not the end of this particular thread in Keith Reid's long

involvement in the music business. He mentions that these are by no means the

only songs that he's written with the present collaborators, and that there were

'plenty of other items that might have made the cut'. There was theoretically

room for another five or so songs on the CD but, as Keith says, '55 minutes seems plenty:

sometimes too much is worse

than not enough. These are just music and words that I'd like people to hear.'

So let us hope that the album gets a lot of radio exposure, and that people

really do hear it.

Click here to pre-order your own copy from Amazon: it's a highly listenable,

rewarding CD, distinguished by excellent writing and singing. 'I'm hoping this will be only Volume I,'

said Keith Reid, winding up his brief chat with BtP about the album. That's our

hope too.

Roland Clare

|

The album can be pre-ordered,

as of 1 September 2008, from Amazon UK: shipping will be 15 September:

click here |

And a solo album of a most unusual sort, held together by the writing of the

words, rather than by any particular composer or performer: it harbours music of

many styles, and features many voices: and it's all very appetising, moreish

stuff. Reid himself is the eponymous 'thread', and the CD graphics

(by guitarist / Dylan-illustrator

Eugen Kern-Emden) make this clear: on the front cover a pink-trousered figure – an everyman

figure, or the lyricist himself? – walks into the frame, trailing a thread that on other pages appears festooned among the branches of a

tree (no worm in sight), then encircling the publisher-details, and latterly, on the

back cover, in the grasp of a crouching ape. Is the ape reeling this umbilicus

in, or paying it out? The relationship between man and monkey will be made

explicit as the album unfurls!

And a solo album of a most unusual sort, held together by the writing of the

words, rather than by any particular composer or performer: it harbours music of

many styles, and features many voices: and it's all very appetising, moreish

stuff. Reid himself is the eponymous 'thread', and the CD graphics

(by guitarist / Dylan-illustrator

Eugen Kern-Emden) make this clear: on the front cover a pink-trousered figure – an everyman

figure, or the lyricist himself? – walks into the frame, trailing a thread that on other pages appears festooned among the branches of a

tree (no worm in sight), then encircling the publisher-details, and latterly, on the

back cover, in the grasp of a crouching ape. Is the ape reeling this umbilicus

in, or paying it out? The relationship between man and monkey will be made

explicit as the album unfurls!

So, to the current album, in which his collaborations with some top

singers and composers are released under the umbrella title of 'The Keith

Reid Project'. It opens very strongly with John Waite's emotional and appealingly

melodic

So, to the current album, in which his collaborations with some top

singers and composers are released under the umbrella title of 'The Keith

Reid Project'. It opens very strongly with John Waite's emotional and appealingly

melodic The second offering is the 'original version'

of

The second offering is the 'original version'

of

The music takes a sparser turn for the minor-key

The music takes a sparser turn for the minor-key

A Common Thread

is another lyric encountered in the

A Common Thread

is another lyric encountered in the

Next, a song about a graveyard. Potters Field is

Next, a song about a graveyard. Potters Field is

The Only Monkey is the album's most recently-recorded track. It's a

stingingly satirical swipe at homo sapiens, mordant, insistent, and

bleakly hilarious. 'The human is a monkey with a diseased brain' (later 'heart',

latterly 'soul') in Reid's vision: he 'makes killing a game', 'takes pleasure

from pain', 'blows things apart', and – uniquely in the animal world – he 'needs

things to do' and is 'in search of a goal'. The middle-eight section runs, 'he'll

sell his own soul for a gallon of gas' (not 'petrol' as it's known in the UK!),

'turn trees into paper to wipe his own ass'. This sort of scathing wit is worth

reams of pious eco-cant, and it is brilliantly set to music by a collaborator

Reid has long admired, the marvellous

The Only Monkey is the album's most recently-recorded track. It's a

stingingly satirical swipe at homo sapiens, mordant, insistent, and

bleakly hilarious. 'The human is a monkey with a diseased brain' (later 'heart',

latterly 'soul') in Reid's vision: he 'makes killing a game', 'takes pleasure

from pain', 'blows things apart', and – uniquely in the animal world – he 'needs

things to do' and is 'in search of a goal'. The middle-eight section runs, 'he'll

sell his own soul for a gallon of gas' (not 'petrol' as it's known in the UK!),

'turn trees into paper to wipe his own ass'. This sort of scathing wit is worth

reams of pious eco-cant, and it is brilliantly set to music by a collaborator

Reid has long admired, the marvellous

Silver Town, sung by

Silver Town, sung by

The

legendary Terry Reid has a hard act to follow, as the running-order has panned

out. Too Close to Call is a night-time FM radio-oriented piece, and his

striking voice, with its haunting falsettos, is ghosted by a female vocalist –

almost inaudible at times – to very interesting effect. The music is credited to

Barry Goldberg (

The

legendary Terry Reid has a hard act to follow, as the running-order has panned

out. Too Close to Call is a night-time FM radio-oriented piece, and his

striking voice, with its haunting falsettos, is ghosted by a female vocalist –

almost inaudible at times – to very interesting effect. The music is credited to

Barry Goldberg (