'Taking Notes and Stealing Quotes':

Drunk Again

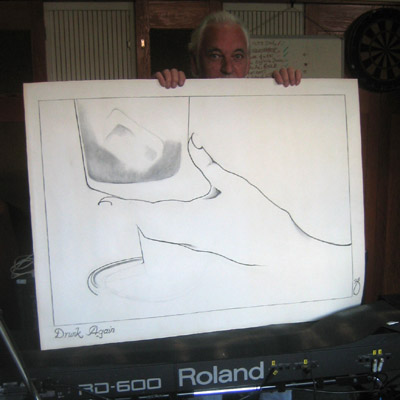

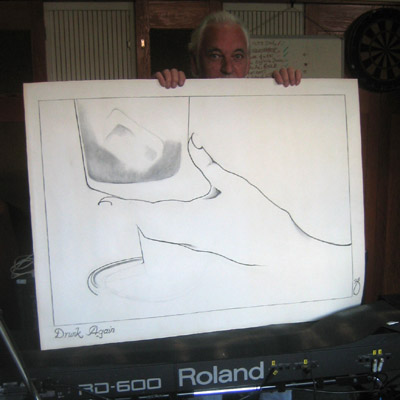

This

rumbustious song was the first number written by Brooker and Reid for the Exotic

Birds and Fruit album, on which, of course, it did not eventually

appear: since it was illustrated by Spencer Zahn in the style of the Grand

Hotel booklet-drawings (see left), we may surmise that the text existed as

early as the time of that album. It is said that the song was elbowed out of Exotic

Birds by a last-minute creation, New Lamps for Old. It does bear a

musical relationship to several songs on the album, however: to The Idol,

in terms of its protracted soloing; to Monsieur R Monde in its flat-out

pace; and to Butterfly Boys in its mature elaboration of some pretty

ordinary rock components. Arguably it's the least melodic of all the contenders,

but it is nonetheless an energetic and exciting track in which we can clearly

hear five musicians (six, if you include the doppelganger acoustic guitar)

thoroughly enjoying themselves.

This

rumbustious song was the first number written by Brooker and Reid for the Exotic

Birds and Fruit album, on which, of course, it did not eventually

appear: since it was illustrated by Spencer Zahn in the style of the Grand

Hotel booklet-drawings (see left), we may surmise that the text existed as

early as the time of that album. It is said that the song was elbowed out of Exotic

Birds by a last-minute creation, New Lamps for Old. It does bear a

musical relationship to several songs on the album, however: to The Idol,

in terms of its protracted soloing; to Monsieur R Monde in its flat-out

pace; and to Butterfly Boys in its mature elaboration of some pretty

ordinary rock components. Arguably it's the least melodic of all the contenders,

but it is nonetheless an energetic and exciting track in which we can clearly

hear five musicians (six, if you include the doppelganger acoustic guitar)

thoroughly enjoying themselves.

Lyrically the song is sparsely intriguing: curiously some of the words are

not reproduced on the CD booklet. It seems to deal with the haverings of an

alcoholic, knowing he should jettison his habit, yet unable to summon the will

to do so (some have wondered if it is to be read as a drunkard's dream, since

the DTs are an established topic in country-ish music). It belongs in the Grand

Hotel camp, as a number about excess of appetite, rather than in the world

of Exotic Birds (which even contains a song (ostensibly) about Sensible

Eating!) Musically, it depends upon two contrasting ideas the belting rocky

chords, riding on Cartwright's nifty bass riff, and the more static, bluesy

climbing passage and the dialogue between these two elements does something

to dramatise the narrator's dilemma; its slightly shambolic sound, like Mabel

and Good Captain Clack, perhaps suggests an ambience in which drinking,

rather than abstinence, is the norm.

Set in the piano-boogie key of C, the song nevertheless starts with some

crunching guitar: this same rhythmic motif was heard in live versions of Typewriter

Torment later on. The verse is built on the highly characteristic Brooker

dominant-dodging sequence of C, Bb, F and C (a relationship underlying numbers

such as Long Gone Geek, Without a Doubt and The Piper's Tune):

when this shifts up on to F and F sharp diminished (shades of Lime Street

Blues) it does briefly touch on the dominant, G, but seems to recoil from it

quickly, and on the second occasion that it reaches that harmonic plateau it

wrestles about with the chord, skittishly repeating the little melodic tag that

precedes 'though I know I'm very sick'. The chorus, if such it be, uses a

standard blues progression with a rising bassline, though the organ-saturated

treatment here gives it an ecclesiastical and highly Procolian flavour; the

quavers are now grouped 3+3+3+3+2+2 over two bars, and this halting sequence

seems to lug itself, Sisyphus-like, up the hill on several occasions only to

collapse back under its own burden

fitting the song's theme precisely.

Nothing But The Truth / Drunk Again (CHS 2032) was released as

a single on 6 April 1974 in the UK. Drunk Again was a collectors item

like its fellow-drinking song This Old Dog it was never to see album

status until it became available as a bonus track on CD re-releases of Exotic

Birds and Fruit. It is quite a typical Procol B side, uninhibited and

relatively rough-edged, like Lime Street Blues, Good Captain Clack,

Long Gone Geek. The performance on record is hugely enlivened by Gary

Brooker's whoops and other cries (including 'lets hear those eighty-eights!'

before his own break), by the whirling organ and whining guitar, the pounding

piano up at the milk-bottle extremities, and of course by the manic precision of

the drum-breaks each time the hill-climbing chords give up. Arguably the melee

of soloing is a bit protracted for a recorded song, but it always sounded very

exciting live from its dιbut in Paris 8 October 1973 it surfaced

occasionally, often at the end of a show, until 1977 and the present track

certainly has a live feel to it. The 1974 Musikladen Live DVD

commemorates an excellent performance of the song no acoustic guitar, and

Copping energetic with tambourine!

- 'I've been out of weeks for ages': this is a provoking paradox to start a

song; 'out of', here, seems to imply 'lacking' as in 'out of luck': the

habitual drinker feels that he is losing whole weeks, thanks to his state of

mind, and that this has been going on for a long time.

- 'on and off the train': the Brooker / Reid repertoire contains ghost

trains and trains to Niagara even A Salty Dog had its genesis in

a train-siren but the here we must assume that its the Whisky

Train that the narrator has mounted and quit. 'On and off' suggests a

repeating sequence, rather than a finite alternation. Incidentally to be

teetotal is to be 'on

the wagon' another transport idiom relating to abstinence, or its

lack. We also talk about a 'train of thought', and that is something that

Keith Reid shows to be derailed in the present number.

- 'losing sheep and counting sleep': counting (imaginary) sheep has long

been proposed as a means of helping oneself to get to sleep; here the terms

are reversed, presumably to imply the drinker's fuddled wits. The song may

allude to insomnia driving one to drink, and hence takes its place among the

Procol night-torment songs (cp Something Magic, Glimpses of Nirvana).

Later in the song Reid uses 'I once heard that a fly can't bird', another

example of this reversal of terms, hingeing on the fact that 'fly' can be

read as a noun but 'bird' is not usable as a verb, and with the refinement

that the sentence is incorrect either way round. Another Procol drinking

song, Good Captain Clack, uses fuddled speech 'jumberlack' for

'lumberjack' to represent alcoholic haze, but in fact there's a strong

tradition in the UK of Nonsense-for-its-own-sake, or for the sake of the

fresh world that word-play can notionally give us access to: children's

playground songs such as The Twenty-First of Liverpool (see here)

use similar verbal reversals 'It's the twenty-first of Liverpool, the city

of July ... The goat took sick that very night and died three weeks before'

and so on. Incidentally this ditty also includes 'punch my ticket', which we

will find in Reid's song below.

- 'And I've drunk too much again': this is one of the songs whose title is

not exactly heard during the song. Another number of the same name was on the

second 1967 album by Bristol's Adge

Cutler and the Wurzels, written by John Macey and Reg 'Snake'ips'

Quantrill, 'the Elvis Presley of Chewton Mendip'. Their first

1967 album contained a song called Mabel, Mabel, by Adge Cutler

himself: a tale of 'passion and pigs' from 'the old Arab quarter of Midsomer

Norton'.

- 'But I'll take another cup': it's noticeable that the lyric rings changes

on the beverage utensil, from verse to verse, and rhymes each one

appropriately.

- 'Even though it dry me up': too much liquor has a dehydrating effect and

can dry up a person's conversation, or an author's flow of words (a problem

addressed in some detail in the next album). An alcoholic who goes for

clinical cure is said to be being 'dried out'. The variant 'even though it

burn me up' shares the awkward syntax, and recalls Whisky Train's

'I'm tired of burning in the flame'. To be burned up is usually 'with

desire'

but whereas the Whisky Train narrator resolves to 'find a

girl' as an alternative to drinking, this song presents only an old woman

Mother Hubbard and she runs away with a chair.

- 'Though I know it's a time to pass': the context here is one of social

drinking, where 'pass' signifies dropping out of the cycle of buying rounds,

or resisting an offer of drink: more alarmingly, 'time to pass' could be the

moment of fainting from intoxication.

- 'I will take just one more glass' / 'another drop' / 'just one more sip' /

'another shot': by varying the terms used, the drinker perhaps seeks to

represent to himself that he is not compulsively repeating exactly

the same behaviour. Reid refers, ruefully, to a drinking glass in the John

Waite song In God's Shadow ... 'and you find a lot of wisdom there at

the bottom of the glass'.

- 'The cellar is empty, the cupboard is bare': cellar and cupboard are both

storehouses for food or drink, and these images of poverty and neglect again

suggest the decline of the drinker's householding skills. 'Cupboard is bare'

is closely related to the Mother Hubbard rhyme mentioned below. The Procol

biography tells of a spate of 'literally starving' in a grim basement

cellar for members of the earliest band but Reid was not among them.

Cellars do occur elsewhere in his work 'In the cellar lies my wife' (Mabel);

'Cellar full of diamonds' (Memorial Drive); 'Put Mohammed

in the cellar' (Poor Mohammed) with markedly different contents.

There might be some profit in considering this ransacked cupboard in terms

of a writer's storehouse of images and inspiration, since the idea of

'emptiness' recurs in Procol Harum songs: 'got the only empty seat' (Something

Following Me); 'The houses were open, and the streets empty' (Dead

Man's Dream); 'The presses are empty' (Broken Barricades);

'I came home to an empty flat' (Toujours L'amour); 'So sad

to see such emptiness' (Nothing But the Truth); 'broken

promise empty lie' (Fool's Gold); 'I was feeling kind of

empty' (Last Train to Niagara)

- 'I'm joining the church and taking to prayer': some religions or sects

preach strict abstinence from alcohol.

- 'The landlord's complaining': in view of 'rent' below this landlord is

probably one who lets out property to tenants; however there are landlords

in public houses too; it's even been suggested that this remark implies

resentment at being in thrall to the record company. As the 'landlord' is

mentioned directly after 'church' some have seen it as a reference to God,

complaining that the sinner has turned to prayer only in desperation, not in

penitence.

- 'cos the rent is outstanding': 'outstanding' means 'unpaid' here, not

'remarkable'.

- 'Old Mother Hubbard's ran off with the chair': 'ran off with' often has

connotations of elopement (cf Jailhouse Rock: 'if you can't find a

partner use a wooden chair') but is more likely to be a matter of

confiscating the last stick of furniture, in lieu of payment of rent or to

provoke departure, the tenant's cash having all been spent on drink. In any

event, the image is one of sheer desolation. Old Mother Hubbard is a nursery

rhyme character, who went to fetch her dog a bone but found the cupboard was

bare. It was written in 1805 by Sarah Catherine Martin at Kitley in Devon

(in the house of John Pollexfen, bastard: Mother Hubbard may have been the

housekeeper there.) This fourteen-verse nonsense rhyme borrows from

tradition in its first three stanzas, which had already appeared on sheet

music. In each of them Mother Hubbard goes off to get something for the dog,

who is doing something totally unrelated in the last line. She visits a

baker's, an undertaker's, an alehouse, a tavern, a fruiterer's, a tailor's,

a hatter's, a barber's, a cobbler's, a seamstress, a hosier. In the last

verse a dame makes a curtsy and the dog bows

as he will do in Taking

the Time in the next Procol album. The only mention of a chair comes in

Stanza 5, where the dog sits in it

- 'Come on Captain, punch my ticket': this enigmatic line is marvellously

delivered on the record, and has attracted a certain amount of speculation.

The Captain is a significant presence in A Salty Dog, and makes a

brief return in the unpublished Last Train to Niagara; but surely the

prime candidate here is Captain Clack, perhaps a fellow drinker to the

present narrator. 'Captain' is a slang word associated with money: in the

60s it was Australian slang for someone with money to spend on his mates [in

the Copping video Keith Reid declares that 'Peter Clack' is 'a friend of the

band, he's an Australian gentleman']. In the 1950s in the same region

'Captain Cash' was the member of a gang who, having recently come into

money, would be expected to pay for drinks. As for 'punching the ticket',

contemporary mentions found on the web suggest that the phrase is being used

to mean 'mark my card' or 'hunt me down' ("Thanks, guys. I thought they

were about to punch my ticket back there (here

see also here

and here)).

But a more established use belongs in the world of public transport (the

train image again) where a ticket is punched, with a machine, to validate it

for the particular journey. 'Punch' is of course the name of an alcoholic

drink, and brings to mind notions of being 'punch drunk'. 'Ticket' is also

slang for a tab of LSD (the narrator buys one in A Rum Tale).

- 'Call my mother's name': the mother's name is supposedly one of a man's

dearest memories (it's also a commonly-chosen idea for a password, as it is

private and impossible to forget it). Mothers are uncommon in the Reid

songs: 'Can't you hear me mother calling you?' (Crucifiction Lane);

'you have caused your mother great distress' and 'you wouldn't take your

mum's advice': (The Piper's Tune); fathers get a brief look-in during

'Something for the mums and dads' (TV Ceasar); otherwise there is

only the Dalai Lama in Glimpses of Nirvana. 'Call my mother's name'

has something of the flavour of a prayer, even a lost cause: it is certainly

very different in tone from 'Call my mother'.

- 'I will take another shot': a 'shot' is a measure of liquor, such as rum,

but it can also refer to narcotic drugs. 'Take another shot' is blissfully

ambiguous, since it often means 'have another go' in contexts where the

persistence would be applauded.

Thanks to Frans

Steensma for additional information

about this song

This

rumbustious song was the first number written by Brooker and Reid for the Exotic

Birds and Fruit album, on which, of course, it did not eventually

appear: since it was illustrated by Spencer Zahn in the style of the Grand

Hotel booklet-drawings (see left), we may surmise that the text existed as

early as the time of that album. It is said that the song was elbowed out of Exotic

Birds by a last-minute creation, New Lamps for Old. It does bear a

musical relationship to several songs on the album, however: to The Idol,

in terms of its protracted soloing; to Monsieur R Monde in its flat-out

pace; and to Butterfly Boys in its mature elaboration of some pretty

ordinary rock components. Arguably it's the least melodic of all the contenders,

but it is nonetheless an energetic and exciting track in which we can clearly

hear five musicians (six, if you include the doppelganger acoustic guitar)

thoroughly enjoying themselves.

This

rumbustious song was the first number written by Brooker and Reid for the Exotic

Birds and Fruit album, on which, of course, it did not eventually

appear: since it was illustrated by Spencer Zahn in the style of the Grand

Hotel booklet-drawings (see left), we may surmise that the text existed as

early as the time of that album. It is said that the song was elbowed out of Exotic

Birds by a last-minute creation, New Lamps for Old. It does bear a

musical relationship to several songs on the album, however: to The Idol,

in terms of its protracted soloing; to Monsieur R Monde in its flat-out

pace; and to Butterfly Boys in its mature elaboration of some pretty

ordinary rock components. Arguably it's the least melodic of all the contenders,

but it is nonetheless an energetic and exciting track in which we can clearly

hear five musicians (six, if you include the doppelganger acoustic guitar)

thoroughly enjoying themselves.