‘Where had I been? What could it mean?

It was dark in the death room as I slithered under …’

Horrors! Oh my! And where, for that matter, were David Knights and Matthew Fisher? Where had they gone? What could that mean?

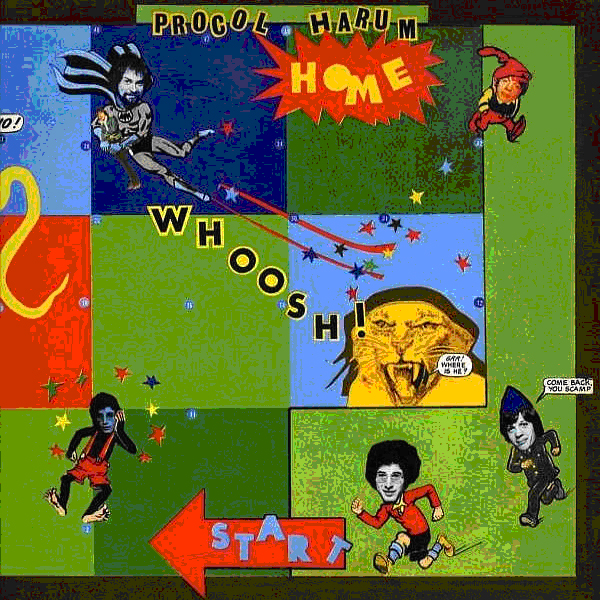

Rewind: I have related previously some of my late 60s/early 70s record store experiences in earlier write-ups of Shine On Brightly and A Salty Dog, so … with your permission, here’s another little story, this time about Procol #4, known as Home (some have thought its title was Whoosh! – see the cover!). In those days, we record-store workers often had little advance publicity of new releases (no Internet, just new replacement pages for the giant Phonolog Reports once a week or so), especially ‘minor’ releases such as this. I tried to ignore most of the music industry hype and other goings-on – these things tended not to interest me much then (nor do they now, for that matter!). However, I had heard that Procol Harum, of which I’d become a dedicated fan, had gone through some personnel changes since A Salty Dog (probably from Rolling Stone, which was still worth reading then); I’d been pretty much knocked out by SOB, and ASD had become my favourite album by anybody. However, I wasn’t prepared for Procol without Matthew Fisher! Anyway, the new album finally arrived: perhaps three or four copies for our shop (Procol were still not very big sellers at the time), plus a promo copy to play in the store.

We

staff gathered around after hours (we did that then – it was a labour of

love) to have a listen – that was hard, believe me: I was the Procol

fan(atic), but the others were less so, so it took some convincing on my

part. Anyway …. first impression, and on this we all agreed: great cover!

What fun! Snakes and Ladders, but a sort of demented version. We determined

quickly the band still had the core songwriting pair: Keith Reid, wordsmith,

and Gary Brooker, piano and vocals, plus the holdovers – guitarist Robin

Trower and percussionist BJ Wilson. But gone, alas, were two original

members: virtuoso organist Matthew Fisher and (underrated) bassist David

Knights. Replacing them, doing double-duty on Hammond organ and electric

bass, was Chris Copping. (Although I didn’t know it at the time, his

presence meant a reunion of sorts of the early-60s Southend R&B combo The

Paramounts: all (save Reid) had been Paramounts (reportedly the Rolling

Stones’ favourite R&B group) at one time or another, although never at the

same time).

We

staff gathered around after hours (we did that then – it was a labour of

love) to have a listen – that was hard, believe me: I was the Procol

fan(atic), but the others were less so, so it took some convincing on my

part. Anyway …. first impression, and on this we all agreed: great cover!

What fun! Snakes and Ladders, but a sort of demented version. We determined

quickly the band still had the core songwriting pair: Keith Reid, wordsmith,

and Gary Brooker, piano and vocals, plus the holdovers – guitarist Robin

Trower and percussionist BJ Wilson. But gone, alas, were two original

members: virtuoso organist Matthew Fisher and (underrated) bassist David

Knights. Replacing them, doing double-duty on Hammond organ and electric

bass, was Chris Copping. (Although I didn’t know it at the time, his

presence meant a reunion of sorts of the early-60s Southend R&B combo The

Paramounts: all (save Reid) had been Paramounts (reportedly the Rolling

Stones’ favourite R&B group) at one time or another, although never at the

same time).

Needle drop: first up – Whisky Train: Oh boy! Just a great Crossroads-like (Clapton/Cream version) guitar line. All right, now – this was really fine! We knew Trower was one hell of a guitar player – Repent Walpurgis, Grand Finale, Long Gone Geek, The Devil Came From Kansas, Wish Me Well and Juicy John Pink – and this confirmed it. So no surprise here. But, following Whisky was an abrupt change of pace in The Dead Man’s Dream, which was ... well, what was it? A bit like the Procol Harum we knew and loved, I suppose, but more macabre, certainly different. And unexpected. And macabre. Complete with some atmospheric (ie horror drama / funereal) organ lines from new boy Copping. One commenter in the BtP pages has since pointed out, ‘The melody is very standard for morbid funeral music … the organ in the background helps add a terrific feeling of gloom, and the lyrics are so incredibly disturbing that they actually manage to become engaging.’ Hmm. Engaging indeed: one word for it, I guess. Or to put it another way, the lyrics couldn’t be unheard! Another (Facebook) friend recently responded to a comment of mine, suggesting that this album, and this song in particular, was a precursor to the 70s gothic-rock cult (eg Alice Cooper and Billion Dollar Babies) and the later 80s/90s Gen-X interest in the genre. Anyway, for us life seemed simpler in 1970: young and of course poised to take over the world, we were not very receptive to this kind of doomy, gloomy darkness. My initial encounter with Dream coloured my thinking on the rest of this album to the extent that, for years, it had remained way down my favourites list.

And so it was that later … since we were there anyway, we checked out the remainder of the album. There was more decidedly mixed reaction among us to next six songs. The occasional (usually black) humour in Home was largely lost on us at the time because of the dominant and pervasive death imagery in many of the songs. Certainly the somewhat sadistic ‘revenge-rock’ of Still There’ll Be More was pretty hilarious (haven’t we all, at some time, felt like doing a few of those things to someone’s door or to their Christmas?).

One of us thought About To Die sounded like a rip-off of To Kingdom Come from The Band’s Music From Big Pink; The Band, being four-fifths Canadian, were of course hugely popular at the time among us biased Canadians, not to say the rest of the world. Even the phrase ‘kingdom come’ was in the lyric of About To Die. But, I suppose, what with the time-honoured tradition of admiring, then copying … this happened all the time, it seemed, and the idea of ‘rip-off’ hadn’t yet become as much of a ‘thing’. Others have since attempted to refute the idea; I tend to take the view (then and now) that all good musicians are influenced by what they hear to a greater or lesser extent, and if some of what they hear spills over into their compositions – well, so be it. Imitation, indeed, is often the sincerest form of flattery.

Piggy Pig Pig reminded me of a kind of revised and updated I Am The Walrus: it similarly rocks hard, but the similarities end there. Its theme is also, in keeping, somewhat grim, but it’s sung almost gleefully, especially the repeated title refrain at the end fade-out – some of us were chanting ‘goo-goo-ga-joob’ whilst Gary and co were ‘piggy-pig-pigging’! In many ways, it’s actually a pretty funny song – zany, even, and a bit of a relief from the dead seriousness of Dream and Die.

Nothing That I Didn’t Know, about a young girl (Jenny Drew) who died before her time, features a quietly finger-picked acoustic guitar, punctuated by funereal drum rolls from BJ and a very effective understated organ line from Copping. Interesting – there’s relatively little organ in evidence overall in Home, but what’s there is very nicely done, and reminds us that this is, after all, Procol Harum. Although Fisher is missed, CC is a fine organist. The song has this pervading feel of sadness, melancholy – it somehow seems more personal than the preceding songs. Perhaps its folk-song feel contributes to that.

Barnyard Story is in perfect keeping, in the morbid, ultimately depressing mould of the album – Keith Reid is at once reflective (‘I was trying not to fall…’), with hints of optimism (‘Now and then my life seems truer, now and then my thoughts seem pure…’), but then … no … down again (‘…maybe death will be my cure.’).

Whaling Stories was in the more ‘familiar’ Procol Harum style (my initial reaction: now, that would have fitted on A Salty Dog, with Hesperus as Part II, even. Maybe, it could have been switchable with The Devil Came from Kansas). Of course, I realized later that Whaling Stories probably hadn’t even been written, never mind recorded, in time to have allowed its inclusion on ASD; besides, Wreck of the Hesperus probably supplied enough drama on its own. Whaling Stories is ‘a nightmarish sea-shanty,’ avers Gary Brooker; it has ‘almost Wagnerian … epic proportions.’ As the album’s mini-epic, it has the drama and majesty of the Fisher-influenced songs from A Salty Dog and earlier. Even if it might have fitted well on the previous album, it slots in here just fine, with its violent horror imagery (especially in the third stanza).

The finale, the food-for-thought-provoking Your Own Choice, is a terrific closing song, and represents a great sigh of relief, in a way, ending the album with a little wisdom, but also with some pessimism (‘The human face is a terrible place / Choose your own examples’). It has a relatively light-hearted, up-tempo feel, and its (deliberate?) false start and terrific chromatic harmonica solo (by one Harry Pitch) is rather refreshing.

So, for the most part, Home was (and still can be, for some) pretty depressing, especially if it’s ‘allowed’ to be. The listener may need to ‘prepare’, or at least be in the right mood, before listening to it (at least, so it has been for me). Keith Reid has recently admitted that he must have been going through some things at the time; he later seems almost (almost) apologetic about the depressing lyrics. Another commenter in the BtP pages said, nearly twenty years ago: ‘Home is one of the most god-awful depressing albums of the 20th century. The lyrics are so strongly of the ‘let’s-all-go-kill-ourselves’ variety as to make me long for the ‘few tweet-tweets’ again.’ (I trust ‘tweet-tweets’ refers to a Gary Brooker concert remark about the seagull sounds at the beginning of A Salty Dog). The commenter’s remark may be a little over-the-top (but only a little!), but many felt that way and still do. But many don’t, I’m sure. Home has come to be recognized as one of the truly great Procol albums, and it’s the outright favourite of some. It signalled a different direction for the band. I, like many, had been so partial to the early Procol and their First Three that I ended up drifting away from the band for a while.

But … that was then, I suppose. I was in my early 20s in 1970, and, as mentioned before, tended to look at life from ‘one side, then’ (sorry, Joni). 45-odd years on, ‘another’ side or two gradually emerged, kicking and screaming sometimes. The usual attempt at maturity (still working on that!) and acknowledgement of some of life’s … subtleties have resulted, among other things, in my discovery of new life and fresh delights in Home. Instead of being at or near the bottom of my list, I’m finally seeing its qualities. Being a little older now (‘a wise man’s fool,’ indeed), I have a renewed appreciation for a really fine album. Indeed, it’s one of the best in the entire Procol Harum canon. I’ve thoroughly rethought my earlier impressions; I hadn’t given it much thought since 1970. I had found it so shattering at the time, but in 46 years, I’ve apparently changed.

A further few points: a poet’s job (one of them, anyway) is to highlight and amplify the truth; Keith Reid (he was and is, to be sure, a poet, and a good one!) has done ‘all this and more’ here. I’m thinking that, in my mid-twenties when this was released, I wasn’t prepared for (and probably not even interested in) the ‘Home’-truths he offered; hence my initial indifference, even hostility towards the album, with its weird themes and, worse, without Matthew Fisher! As we were taught earlier in Look to Your Soul: ‘… For the lesson lies in learning and by teaching I’ll be taught / for there’s nothing hidden anywhere, it’s all there to be sought.’

It’s almost as if Keith sensed Home was ending their early phase: ‘choose your own examples’ and ‘draw your own conclusions’. In other words, ‘grow up, everybody’! Indeed, this album, for me, marks the beginning of the ‘mature’ Procol Harum: a seamless blend of the ‘old’ Paramounts-like hard rock (Whisky Train); the well-established prog tendencies of the quasi-apocalyptic Whaling Stories; the folky (albeit a bit gloomy) tone of Nothing That I Didn’t Know (the latter two might have fitted well on the Salty Dog album). Some see Home as their best album; others see it as a kind of breakout from the old ways, allowing them to settle into the 70s with a series of six more good-to-great albums. Gone are the lyrical/whimsical psychedelia of the first album and much of the second. Procol was clearly stretching out, continuing the new directions started in A Salty Dog. Indeed, the departed Matthew Fisher, who had produced that album and was moving towards a career in production, had initially been tabbed to record Home with engineer Ken Scott (ie the same production team as ASD). They had completed tracks on five of the Home songs at Trident Studios in London (which were later scrapped); by then Fisher has said he felt less and less ‘one of the gang’ and quit in frustration, according to the liner notes of the Esoteric edition.

Lastly, and most important perhaps, given the new direction, it rocks, hard, at times! Procol Harum always were rockers at heart; after all, this four-piece version of the band was all former Paramounts, who were best known as a very good R&B cover band in the mid-60s. Whisky Train, Still There’ll Be More, About to Die, Piggy Pig Pig, all reflect a desire to ‘bring some more R&B back into the band’s overall sound’ (Chris Copping, from the liner notes). Copping, the ‘new’ boy, brought this dimension to Procol: he had a more imaginative and funky style as a bassist compared to the more studied approach of David Knights, while his organ work, while lacking the sheer virtuosity of Matthew Fisher, was accomplished nevertheless.

It’s easy to see why this album is the favourite of many: musically brilliant, everywhere, and thematically unified. There is humour, albeit a tad black, and the gloomy bits pull no punches. Interestingly, Trower has two composition credits on Home: Whisky Train and About to Die. His star was starting to rise, and he really came to the fore on this album: two here, three on the next album, then off to a successful solo career.

More evidence of their evolving maturity: Reid and Brooker had recently changed management (for a third time) to a new company called Chrysalis (the right-hand man of the company principals, Doug D’Arcy, became their fourth manager). At the same time, they formed a new publishing company called Blue Beard (Bluebeard?) Music, and also a new production company call Strongman Productions, and later a management company with the latter name. Clearly, not only from their growing maturity with respect to their material, they were starting to get serious about protecting their mutual business interests; so many bands back then, frankly, had been duped by their management and/or publishers: vivid examples around this time were the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Badfinger and many others. These business moves served, among other things, to ensure Brooker and Reid would split all future song royalties on a 50/50 basis.

The Deluxe Esoteric ‘CD edition gives us a nicely remastered original album on Disc 1; the same team as the previous releases in this series was used, and Henry Scott-Irvine again provides interesting and comprehensive liner notes. Disc 2 contains no fewer than eleven (nine previously unreleased) alternate takes, backing tracks, a single (US radio) edit of Whisky Train (which is the sole bonus track on Esoteric’s single disc version of this release), and a George Martin mix of About To Die! (Sir George had been mentor to Home producer Chris Thomas, and the album was, after all, recorded at Abbey Road). There are also two BBC session tracks done for the David Symonds show from May 1970. One of the backing tracks – for Whaling Stories – reveals the instrumental sophistication of which they were capable: the organ playing here could easily have been that of Fisher, and it shows off Copping’s considerable ability. This latter track and another backing track (of Still There’ll Be More) had been included on a previous release on the Salvo label, since discontinued.

Finally, a few words on the album cover and title: Dickinson was back after her previous Procol cover efforts: the very distinctive Ghostly Lady from the first album, and the iconic ‘Hero’ cover from A Salty Dog. This time we have a send-up of the popular children’s board game Snakes and Ladders, with the band members’ superimposed heads atop various cartoonish comic book characters – the best one is ‘new boy’ Chris Copping as ‘whooshing’ superhero (is he a ‘saviour’? I wonder …), flying away from a frustrated, confused lion (the ‘Regal’ Zonophone?). Also notable: Keith Reid as a ‘scamp’ (so he was in many of the lyrics, wasn’t he?) – Robin Trower is chasing him, pleading ‘come back….’ In any event, the warm and fuzzy feel of the title ‘Home’ (together with its ironic, playful cover art) belies its contents.

So why call the album Home? It’s been suggested that it was indicative of the reunion by the old Paramounts line-up, therefore signifying they’ve come ‘home’, as in a family reunion. I might also see it more ironically, in the death-theme context, as ‘coming home’ or ‘going home’ – as a Christian death euphemism.

Home was Procol’s last original album for Regal Zonophone (which was an EMI imprint, similar to Deram with Decca/London); its impending doom was looming (coincidentally with the theme of the album?), hence their change to a new company in the UK, and eventually to the Chrysalis record label (in the UK – they remained with A&M in the US and Canada) for their next album (Broken Barricades) a year or so later. The Esoteric release supersedes the Salvo from 2009, whose bonus tracks are repeated here. I’ve not heard the Salvo, whose remastering was done by some of the same people - I’ve heard it’s good. (By the way, none of the ‘First Four’ Regal Zonophone albums is available any longer on the Salvo imprint, other than as old stock or used), probably for contractual reasons. Those rights have been transferred to Esoteric.)

A crucial transitional album, therefore, signifying a major shift on several levels: definitely, unequivocally recommended. Kudos once again to Henry Scott-Irvine and his excellent liner notes, and my grateful acknowledgment to the webmasters for some information contained in the comprehensive Beyond the Pale website for some of the material repeated here.

© Peter Bourne, January 2017