Procol

Harum and the ESO: Together Again

Tom Murray in The Edmonton Journal, 9

November 2010

Procol Harum’s experimental gig with ESO in 1971 produced one of the bestselling

discs ever

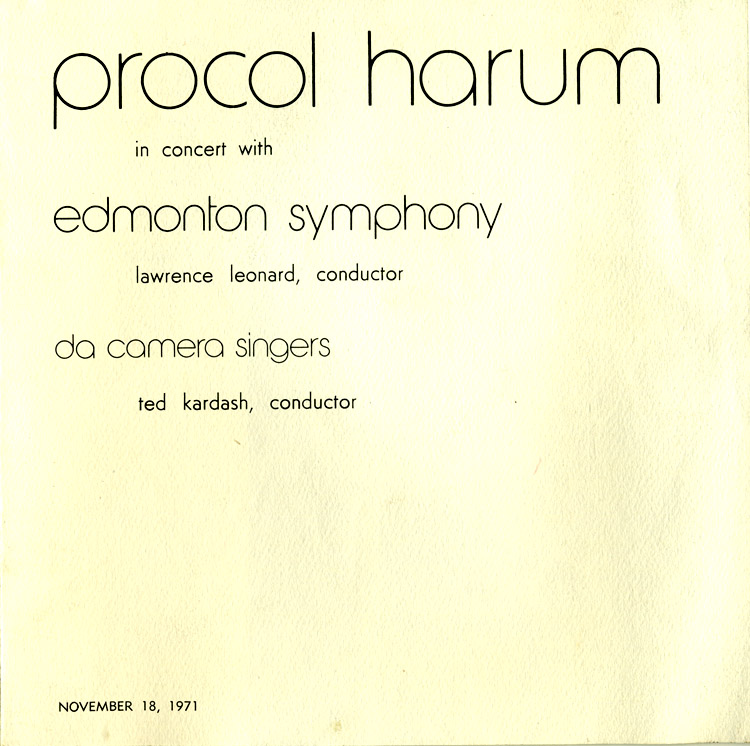

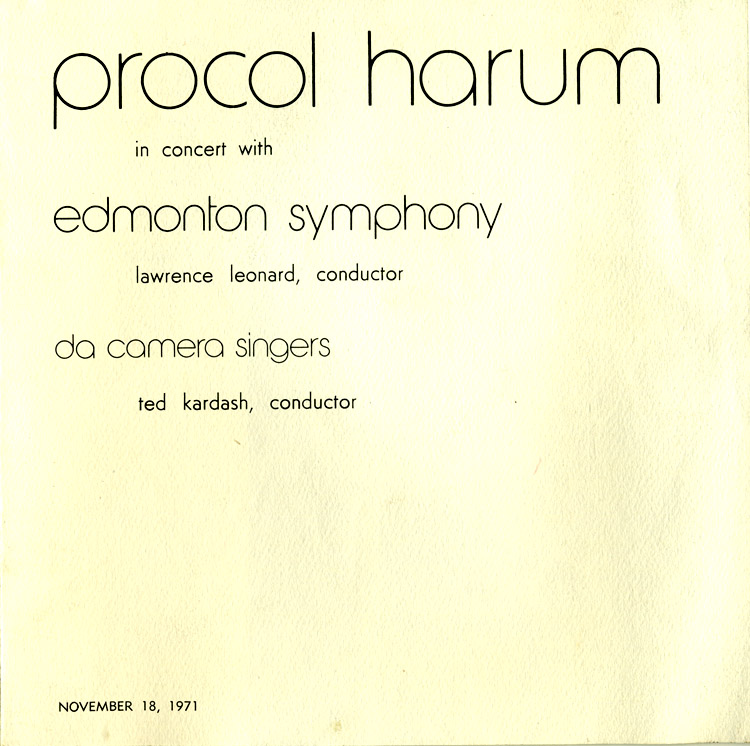

Procol Harum, the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra and Edmonton’s Da Camera Singers

will close a musical loop tonight and Wednesday (see

here).

For two nights at the Winspear Centre, the three intermittent collaborators will

revisit the songs that put them all on the musical map on 18 November 1971, with

the creation of Procol Harum Live With the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra.

Singer

and keyboardist Gary Brooker is the only original member of the band left from

the 1971 concert (as well as the 1992 reunion), but Procol Harum is still busily

touring. Its last album came out in 2003, but one is promised for the end of

2010 and the band is in the midst of remastering and re-releasing several older

albums — Grand Hotel, Exotic Birds and Fruit, Procol’s Ninth

and Something Magic.

Singer

and keyboardist Gary Brooker is the only original member of the band left from

the 1971 concert (as well as the 1992 reunion), but Procol Harum is still busily

touring. Its last album came out in 2003, but one is promised for the end of

2010 and the band is in the midst of remastering and re-releasing several older

albums — Grand Hotel, Exotic Birds and Fruit, Procol’s Ninth

and Something Magic.

The 1971 concert at the Jubilee Auditorium gave Procol Harum its most popular

record, but nobody involved was under the impression they were making history.

It was something of a chaotic event, an experiment that shocked everyone

involved when the recording went on to become one of the biggest-selling discs

ever, second only (at the time) to Bing Crosby’s White Christmas. It

revived Procol Harum’s career and put Edmonton on the map.

The orchestra, the choral group and the English progressive rock band have gone

on to other separate triumphs, but they’re inextricably linked in the minds of

many.

There was a two-night reunion May 29 and 30, 1992, with Brooker leading the

recently reunited band back at the Jubilee (Greenwood Singers subbing in for Da

Camera at that time).

The winding road that brought the three original groups to the 1971 concert

makes sense in retrospect. Bob Hunka, who was then assistant general manager of

the ESO, had brought in the popular Canadian group Lighthouse for two successful

nights the year before; Procol Harum boasted a live performance with an

orchestra in Stratford, Ontario, around the same time. Rock bands from the Moody

Blues to Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention and the Beatles had begun

experimenting with symphonic elements by the mid-’60s. Procol Harum was intent

on pushing the synthesis.

Brooker and Procol Harum’s road manager Derek Sutton met Hunka at the Edmonton

Inn on 7 August, when the band was in the midst of a North American tour. They

agreed on 18 November as the date for the concert in Edmonton.

Now, as the Winspear hosts the 39th anniversary of the original concert, The

Journal took the opportunity to talk about the seminal 1971 event with some

of those who were there.

Beginnings

Bob Hunka: The day after the second Lighthouse concert, I ran into (ESO board

member) Eric Geddes in the office and he said, “I didn’t know who Lighthouse

were before this, and I’m still not sure that I know who they are now, but

congratulations!”

Petersen [sic]: I was working at the CBC in the summer of ‘71, doing audio,

punching in commercials and watching TV. On came the Elwood Glover show

(Luncheon Date), which was this Canadian institution; Stompin’ Tom got married

on Elwood Glover. Anyways, Procol Harum were on, and they’d just done some dates

with an orchestra in southern Ontario. I perked up and phoned Bob because I knew

he was looking for something after the Lighthouse concerts, and I said, “You

should check them out, because they’ve already got charts.” I don’t think he was

interested.

Hunka: I said no, even after he loaned me all his Procol Harum records to listen

to.

Petersen: The Toronto music writer Ritchie Yorke gave him the same advice, so he

eventually came around to it.

Hunka: The most vivid memory I have of them was when we put it together at the

Edmonton Inn. It was like one of those Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney movies:

“Let’s put on a show!” They had a rock band and I had an orchestra, let’s do it.

Three weeks before it all went down, we got word that they had decided to record

the whole thing, bringing in (legendary American sound engineer) Wally Heider

from LA.

Broddy Olson: Nobody really knew them, but Bob did. I remember Eddy Bayens did a

lot of work with the union for us, so he lined up a flat fee of $280 (per

musician), I think, which was unfortunate, because in the end that album sold

millions. (Other reports put the ESO fee at $5,000.)

Eddy Bayens: It wasn’t as strange as you might think The orchestra was always

open to playing other types of music, not just Shostakovich and Beethoven. We

played what people wanted to hear.

Ron Burrow: I was 19 years old at the time, and just moved from Ontario, where I

had seen (Jimi) Hendrix and the Mariposa Folk Fest. There weren’t a lot of large

bands that came through Edmonton, so when they did, it was an event. It wasn’t

an everyday thing; it was very special. You found out through radio ads and

flyers, not Facebook; we just didn’t have the mass knowledge of events that we

have now.

Bayens: Remember, we were also pretty young, and rock was our music as much as

classical.

Robert de Frece: I was 22, and most of the rest of the choir were in their 30s

and 40s. I was very excited when I was told; the others said, “Who?” and I said,

“This is the band that did Whiter Shade of Pale!”

Burrow: For most people, a rock band would have been Led Zeppelin, or the

Stones, or the Who. Procol Harum, like the Moody Blues, were something

different. They were attempting to do new things with rock music and it wasn’t

for everyone.

Bayens: Procol Harum were very good musicians, and these were good songs, not

just the usual three chord rock.

George Blondheim: I had seen them some time before the ESO concert at the

Kinsmen Field House, and Brooker had done this thing where he started a song

with Bach’s Prelude in C before going into the song itself. We ended up

borrowing that idea for our own band.

Hunka: You’ve probably heard it before, but when they got off the plane, the ink

was still drying on the arrangements that Gary had written.

Petersen: They were around for about four or five days, and I ended up driving

(producer) Chris Thomas around because of my interest in producing. We had a

friend, John Butler, who was a professional chef that happened to be from

England, and he also worked as a driver for the group. One night he invited the

band and crew to come up to his one-bedroom apartment on Jasper Avenue to have

curry. We were all squeezed in there.

Hunka: He was (Edmonton businessman and philanthropist) Sandy Mactaggart’s chef.

The food he made was very exotic to the rest of us; it was the first time I’d

ever had paella.

Rehearsal

Guitarist

Dave Ball’s amp breaks, and he has to replace it twice.

Guitarist

Dave Ball’s amp breaks, and he has to replace it twice.

Blondheim: I happened to be in Harmony Cats (music store) when the guitarist and

sound guy came by to pick up a new amp, a second amp and a wah-wah pedal, so we

ended up pestering them with questions.

Bill Dimmer: We were a little bit in awe of them, but I also think that they

were a little in awe of the fact that they were onstage with an orchestra.

Olson: Our conductor, Lawrence Leonard, was from England. I think he was kind of

embarrassed to conduct a rock group, because I don’t recall that his name is on

the back of the album.

From Gary Brooker’s notes on the concert: ‘11.15 to 1.15 discussing concert,

particularly the 1st half (which we had not intended to partake in), which ended

in an argument between Lawrence and myself causing him to say he didn’t want to

do the concert and me telling him he needn’t bother.’

Petersen: It was possible that Lawrence Leonard didn’t want his name on the

project because he felt it was going to hurt his career. The band walked into

that situation and it was unfortunate. None of the orchestra guys seemed to have

the same attitude; they were all enjoying themselves. You could say it turned

out truly to have been a bad career move on Leonard’s part.

Hunka: Lawrence agreed to conduct, but actually wanted a guarantee that his name

wouldn’t appear in any reviews. We got along fine, though, and I’m sure he

eventually bonded with his British music mates. I think he maybe had second

thoughts a few years later because of the success of the album.

Dimmer: It was my first year in the orchestra, and I have a strong memory of

Wally Heider and these two trucks’ worth of equipment. There was all of this

gear lying around, a 32-track (some reports say 16) soundboard and microphones

everywhere. I think he was aware of his position, just shouting commands at

people, and the fact that he was kind of in the boonies.

Lois Lund: There were live mikes everywhere, which was a new experience for me.

You couldn’t even sigh without it being picked up. I remember one very tall man

(Procol Harum road manager Derek Sutton) with curly hair down to his shoulders

walking around barefoot.

Bayens: We only had the one rehearsal. It would have been a problem if the

arrangements weren’t good, but these were good arrangements (by Brooker).

Everything fit [sic] like a hand in a glove.

The concert

For participants, this was a nerve-racking experience. The opening act was

sitarist Larry Reese. Before the band came on, Procol Harum organist and

harpsichordist Chris Copping went on alone with the orchestra to perform

Albinoni’s Adagio.

De Frece: I missed the daytime rehearsal because I had to teach, but I was at

this piano rehearsal Da Camera did with Gary Brooker. He had added this speaking

part to a song, and said, “When I say ‘boiling oil and shrieking steam,’ I want

you to go ssssss.” Well, when I got to the show, the other choir members who had

made the day rehearsal told me, “You know how he wants us to go ssssss?’ Well,

you can’t hear anything onstage because it’s so loud; you have to count measures

to know when to do it.” Sure enough, I was ten feet from the band and I couldn’t

hear anything. I was madly counting measures, and poor Lawrence Leonard was just

slightly off; he’d miscounted and you could tell from how he was pursing his

lips when he wanted us to do the part, but we’d done it just before.

Reese: I stood up to bow (after his performance), not realising my leg had

completely gone asleep from hip to toe, so I fell over and had to limp offstage.

My face was red both with embarrassment and exaltation at having taken part in

this historical rock ‘n’ roll event.

Reese: I stood up to bow (after his performance), not realising my leg had

completely gone asleep from hip to toe, so I fell over and had to limp offstage.

My face was red both with embarrassment and exaltation at having taken part in

this historical rock ‘n’ roll event.

Lund: It was very hard on everyone’s ears. Certainly a symphony is loud, but not

quite as loud as that.

Blondheim: My friend (and then band-mate) Don Johnson got us tickets. It was

such great spectacle.

Petersen: It was kind of an interesting week in Edmonton. Kris Kristoffersen and

Rita Coolidge were in town, and they came to the concert.

Olson: Ed Nixon did the trumpet part in Conquistador (the hit single),

which was very different from what he was used to. He nailed it cold and I

congratulated him on that.

Lunn: We then had to go back out for an awfully long encore to repeat some of

the songs again. It seemed as though we did the concert three times in total.

Afterwards

De Frece: We had a party after. I didn’t get home until 4 in the morning, and I

had to teach in a few hours. I don’t know why, but I hadn’t considered that I

was teaching high school music, and around forty of the kids had been at the

concert. They had seen me onstage in my bubble gum pink shirt with ruffled

sleeves and bell bottom pants and suddenly I was very cool.

Burrow: I went in just wanting to see a rock show, but came out thinking, “Wow,

that was a different approach to bringing two different forms of music

together.” It was revolutionary; my parents’ generation wouldn’t have considered

this to be musical. It took a few years before we realised how historic it was,

of course.

Olson: Later, (ITV general manager) Wendell Wilks and Tommy Banks started the

In Concert series with the ESO, and we’d get people like Tom Jones and

Engelbert Humperdinck in to perform. They came out, found out we were pro, and

after that we did 48 episodes. You’d go anywhere in the world and see Roberta

Flack, Tom Jones or Aretha Franklin and the ESO on television.

Blondheim: I decided after that concert that this was what I wanted to do. It

took some time, because I was self-taught, but I learned to make it happen.

Lund: Every now and again we’d get royalties from that album — not a lot, but it

was still kind of neat that we got anything.

Burrow: I still have a working turntable, so that record does go on from time to

time.

De Frece: I can show people who I am on the album cover — the tall guy with the

curly hair in the ruffled shirt.

Success

According to some reports, Procol Harum had to sell 150,000 copies to break

even.

As they had never sold anywhere near that in their career, they were very

nervous. It went on to sell more than one million copies.

Shine on Brightly,

Luskus Delph, Simple Sister and Repent Walpurgis were also

played, but didn’t make the album, though Luskus Delph was eventually

released.

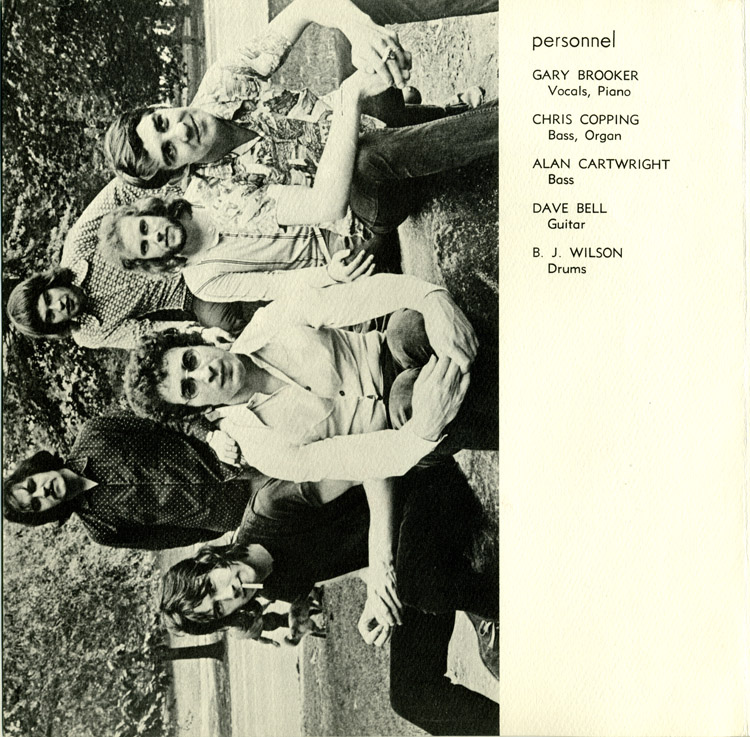

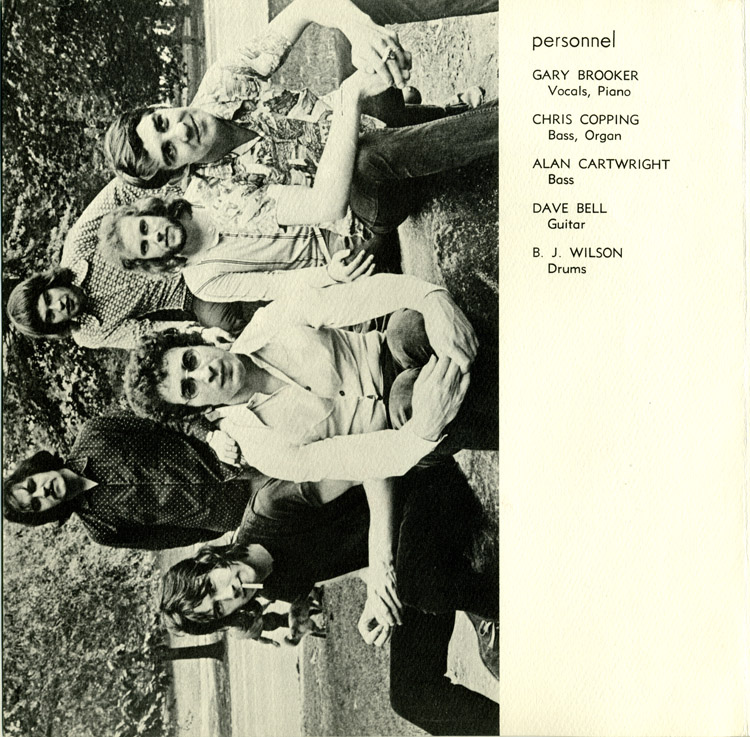

Procol Harum then: Gary Brooker (piano and vocals), Keith Reid (words), BJ

Wilson (drums), Chris Copping (organ), Alan Cartwright (bass) and Dave Ball

(guitar).

Procol Harum now: Gary Brooker (piano and vocals), Josh Phillips (Hammond

organ), Geoff Whitehorn (guitar and vocals), Geoff Dunn (drums and vocals) and

Matt Pegg (bass and vocals).

Many more pages devoted to the Edmonton

concert

More reviews of the Edmonton album

More reviews of other Procol Harum

albums

Singer

and keyboardist Gary Brooker is the only original member of the band left from

the 1971 concert (as well as the 1992 reunion), but Procol Harum is still busily

touring. Its last album came out in 2003, but one is promised for the end of

2010 and the band is in the midst of remastering and re-releasing several older

albums — Grand Hotel, Exotic Birds and Fruit, Procol’s Ninth

and Something Magic.

Singer

and keyboardist Gary Brooker is the only original member of the band left from

the 1971 concert (as well as the 1992 reunion), but Procol Harum is still busily

touring. Its last album came out in 2003, but one is promised for the end of

2010 and the band is in the midst of remastering and re-releasing several older

albums — Grand Hotel, Exotic Birds and Fruit, Procol’s Ninth

and Something Magic.