Procol HarumBeyond

|

|

|

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |

|

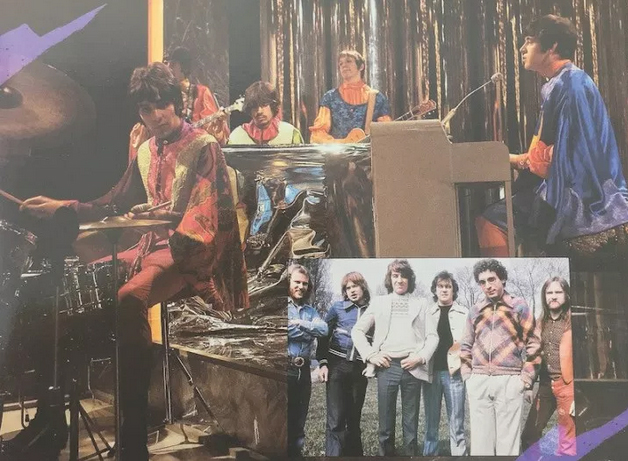

The shot above, which appears in the LP Procol Harum: The Collection, shows BJ Wilson sitting up fairly high, with his snare tilted away from him. In subsequent years he tilted it flatter and sat much lower, to a point well beyond what would look comfortable for most players.

He’s featured on absolutely classic recordings by rock icons like Procol Harum, Joe Cocker, and Lou Reed. He mesmerised Jimmy Page and nearly landed in Led Zeppelin. And most who experienced his playing first hand believe he was one of the best who ever lived.

Had Procol Harum enjoyed greater commercial success during its original run between the late ’60s and mid ’70s, you’d likely hear BJ Wilson’s name mentioned more frequently alongside those of John Bonham, Keith Moon, Ian Paice, Carmine Appice, and Cozy Powell in discussions regarding great rock drummers of the era. He was a star-calibre talent.

Visually, Wilson (born Barrie James Wilson in London on 18 March 1947) was a compelling presence. Once described as looking like an octopus in a bathtub behind the drums, he regularly sat so low that his snare drum was at diaphragm level, forcing him to fully extend his arms to reach the toms and cymbals, all the while playing traditional grip.

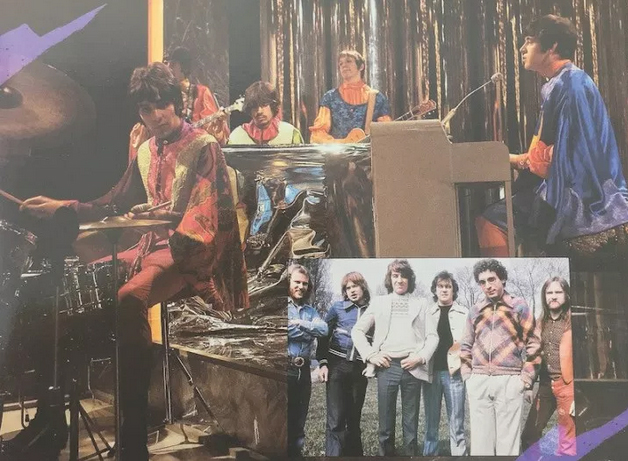

Below, Procol Harum circa 1972: organist Chris Copping, BJ Wilson, singer/ pianist Gary Brooker, lyricist Keith Reid, guitarist Dave Ball, and bassist Alan Cartwright

“Everybody else looked weird to me!” exclaims Procol Harum singer/keyboardist Gary Brooker when asked about his former drummer’s rather unique ergonomics. “He was always fascinating to watch. There are a few DVDs around where you get a good look, but never enough as far as I’m concerned. He’s totally captivating.”

Sonically, Wilson was an absolute force of nature. Comb through Procol Harum’s catalogue, and you’ll discover no shortage of tracks with drumming that will leave you collecting your jaw from the floor.

For sheer excitement, there’s Simple Sister, essentially a spastic drum solo set to halting, orchestral hard rock. The seafaring ballad A Salty Dog finds Wilson flashing more nuanced chops, with his jazzy flourishes, marching patterns, and majestic fills.

The grinding Long Gone Geek and the cowbell-rattling Whiskey [sic] Train show Wilson had a pocket as deep as the best of them. Conquistador — both in its studio and live versions — finds Wilson at perhaps his most dramatic and driving, delivering fills that command attention. And stately ballads like Homburg showed Wilson also excelled at keeping simple time with tons of feel.

We haven’t highlighted the understated swing and those tumbling rolls from Procol Harum’s signature song, A Whiter Shade of Pale, because Wilson isn’t on it. Neither is the band’s briefly tenured original drummer, Bobby Harrison. It’s actually session drummer Bill Eyden who got to play on Pale, a result of the urging of producer Denny Cordell.

Had Wilson exercised some patience, it could have been him playing drums on one of the most recognisable songs of all time. He was meant to be the drummer in this new band started by Brooker, with whom he previously played in a blues band called The Paramounts. But as Brooker and lyricist Keith Reid were trying to assemble Procol Harum in fits and starts in early 1967, Wilson bailed and rejoined another former band, George Bean and the Runners. By that year’s famed Summer of Love, it was Procol Harum, not George Bean and the Runners, enjoying massive international success. Before long, Wilson would be back with Brooker in the band he left before it ever got started. “Once A Whiter Shade of Pale became number one, BJ saw that he should join — and did,” Brooker says with a laugh.

Though Wilson missed out on one iconic classic rock song, he did wind up on another about a year later. That’s him swinging hard on Joe Cocker’s soul-powered version of the Beatles’ With a Little Help from My Friends, a cover that arguably eclipses the original thanks in part to Wilson’s performance. Every element is extraordinary, from his 6/4 feel, to the raw power and boundless imagination behind his fills, to the dynamic sensitivity he employs in playing off Cocker’s stirring vocal. Brooker cites the track as a perfect example of the swing inherent to Wilson’s style (“His work across 6/4 would never be matched by anybody”), marvelling fifty years later at the snare flam and kick combination Wilson uses to bring the band back in after the hushed first verse.

“That drum intro is absolutely killer,” Brooker says enthusiastically. “I wasn’t there, but I can imagine that somebody said, ‘Let’s leave the drums out; you just come in when the chorus comes.’ And he likely said, ‘Okay…here I come.’ [laughs] It’s one of those master-class drum fills that’s filled with courage and imagination and belief. You’ve got to believe in yourself to come in like that.”

Brooker’s not the only world-class musician left amazed after working up-close with Wilson. Jimmy Page, who played guitar on With a Little Help from My Friends prior to forming Led Zeppelin, gave Wilson this endorsement in the biography Procol Harum: The Ghosts of a Whiter Shade of Pale: “There was nobody to touch him. He almost orchestrated with his drumming…with his uniqueness on the kit. And that’s what he had. He was very special indeed. There was nobody in the world that could drum like BJ Wilson.”

Page was believed to be so impressed with Wilson that he wanted him for Zeppelin, but reportedly changed course when Robert Plant presented John Bonham. While it’s interesting to ponder how Zeppelin would have sounded with Wilson on drums, the rock world certainly didn’t get cheated out of a monster drummer by Wilson landing elsewhere. Just as Wilson was hardly your average rock drummer, Procol Harum was hardly your average circa late ’60s/early ’70s rock band. They eschewed the heavily amplified blues and endless jams of the day, building songs instead around classically tinged piano, swelling B3 organ, strings, and Brooker’s powerful delivery of Reid’s lyrics.

Wilson and Procol Harum seemed a perfect match. The band’s atypical rock ethos afforded Wilson the opportunity to use every tool in his toolkit. And the songs benefited from having a drummer who applied a somewhat jazzier approach (which Brooker says was enhanced by lessons Wilson took with Joe Morello) and had a knack for playing off the vocal melody rather than locking in with the bassist.

“He was very inspirational to me as a singer,” Brooker says. “He knew every word to every song. You’d look out the corner of your eye, and he’d be singing the third verse. He interpreted, in a very subtle way, the lyrical content. He was always listening. I could see in his face that’s what he was playing along to: the lyrics. He wasn’t playing along with the bass player, which is probably what most drummers do. They think that’s what their job is. He knew that the real job of the drummer is to play with the vocalist.”

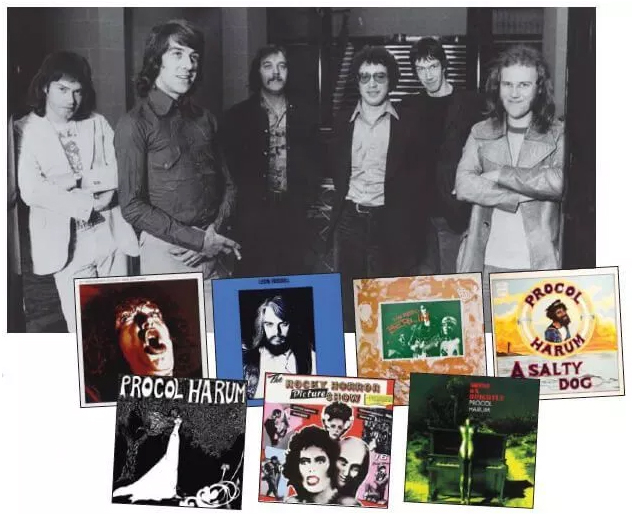

Other artists took notice of Wilson and sought him out during his stint with Procol Harum (he notably played on Lou Reed’s Berlin album and the Rocky Horror Picture Show soundtrack) and after the band disbanded in 1977. Wilson joined Cocker’s backing band in the late ’70s, and was brought in to play on sessions for Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers’ Damn the Torpedoes and AC/DC’s Flick of the Switch, though his tracks didn’t make the final cut on either album. Wilson played with Cocker until 1983, when he was let go due to his alcohol abuse problems.

Wilson would play on Brooker’s 1985 solo album, Echoes in the Night, and had attempted to make a new start in the US, living in Eugene, Oregon, with his wife and children, but substance abuse cut him down in his prime. He overdosed in a reported suicide attempt in 1987, and remained in a coma in a vegetative state until he ultimately died from pneumonia in October 1990.

Brooker formed a new version of Procol Harum after Wilson’s overdose and held out hope his former bandmate would awake from his coma and return to the band. He would regularly visit Wilson and play him demos, hoping it might somehow miraculously rouse the drummer.

“I tried to wake him up,” Brooker says. “I played different things to him. I’d sing to him. We were working on new songs using a drum machine. I’d play him the tracks with the drum machine, hoping he would hear it and go, ‘What the bloody hell is going on? I’ve got to get over there.’”

The album Procol Harum was working on at the time, The Prodigal Stranger, would be released in 1991, dedicated to Wilson. Brooker has kept the band going ever since, using a series of very capable drummers including Mark Brzezicki and Geoff Dunn (who appears on the band’s most recent album, 2017’s Novum), but the spectre of Wilson still looms large.

“Sometimes I do think, I wish he was here, but that isn’t fair to whoever is [on the drums], is it?” Brooker says with a laugh. “Now and again drummers come up to me and say what all drummers should say: ‘BJ Wilson was one of the best ever.’ Jim Keltner said that to me when we were doing the [2002 George Harrison tribute] Concert for George. It’s the first thing he said to me. He didn’t say, ‘Hello, Gary.’ He walked up to me and said, ‘BJ Wilson was the man.’ I’m glad somebody feels like that. Especially a drummer of his capabilities. That’s nice to know.”

BJ WIlson's page at 'Beyond the Pale'

|

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |