Procol HarumBeyond |

|

|

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |

|

'Aching to hear it again'

'I was quite a good boy at school ...' as the old song goes: and the most fun I ever had was putting together a band to play music for a devised theatre-piece, War Play, that critically dramatised the history of conflict in our century - up to 1969, at any rate. My friend Nigel was the guitarist, and he arranged a chronological sequence of jazz excerpts; I was the pianist and did the same thing for popular music. And that's why the show ended with five minutes of Repent Walpurgis.

Its doomy, harrowing ambience fitted marvellously with the apocalyptic finale of the play. Once we'd worked out the chords - or rather, once we'd worked out that the chords weren't all in root position, and that the E flat bass note under the A flat chord lent it a kind of hollowness, and that the D bass note under the F minor chord stopped it from sounding stodgy - we could recycle the four-bar phrase (Peter, playing a minuscule set of drums, was really a church organist and he informed us that Walpurgis was 'a passacaglia on a ground bass', very Baroque) until the improvised onstage warfare ended, then deftly segue into the stillness of Bach's C major prelude while the smallest child in the cast recited the Jeffers poem, Their Beauty has More Meaning ('... black is the ocean, black and sulphur the sky, and white seas leap ... I know that tomorrow or next year or in twenty years I shall not see these things: it does not matter, it does not hurt ...'). Then we blasted back into the minor passacaglia for the curtain-calls, taking our own bows one by one on the crashing chords of the climax. 'I could have listened to that last movement forever!' cooed Mrs Cassidy, a parent in the final night's audience. Strange days!

This young band outlived the play, switched drummers and bass-players, added a lead clarinettist (since we hadn't got an organ in War Play, I'd taken the opening melody on clarinet, swapping to piano after eight bars), and started playing various local concerts. Walpurgis was always our closing number - In the Wee Small Hours of Sixpence, curiously enough, was our only other PH adaptation. In 1970 we all listened to Home, and borrowed the rising scale from Whaling Stories to underpin the end of our Repenting: delightfully this was a device that Procol Harum themselves adopted in the 90s.

Lately I found the scrap of manuscript paper on which I'd transcribed not only the opening organ melody, but also bits of Robin Trower's two main guitar solos from the 1967 recording, for the benefit of Chris, our clarinettist. Chris improvised a lot as well, but at that time we assumed that the Trower lines were a composed part of the song, and imagined that we would not be honouring Matthew Fisher's intentions if we did not reproduce them: particularly those four bars of guitar that precede the Bach ... our piano, guitar and clarinet blasted those out in unison ... and that lovely melody that Robin initiates at 3.25 in the original. We may well have sounded ghastly, but it was superb stuff to be playing. And I believe that it was the unsurpassed balance and build-up of those Trower solos that disposed me to admire this number, which would surely not have struck me so forcefully had my first exposure to it come from one of the less elegantly-disciplined recordings.

Back then I had never heard Procol Harum live, and the original recording was the only one I knew. By the time I heard my first live Walpurgis Copping and Grabham had taken charge, and the music had changed, predictably, understandably. Only in the 90s, when I finally heard its composer play, live and on two more recordings, did I realize quite how mutable the Walpurgis theme was, even the opening eight bars, which I imagined Matthew would leave untouched, as if they were somehow written in stone, the foundation for what followed.

Later still, as I began to be sent tapes of other 60s concerts by various BtP stalwarts, I figured out that the only common element among seven Fisher performances that I owned was the brief note-sequence I have used as a background to this suite of Walpurgis pages (scanned from the 1967 lead-sheet published by Essex music).

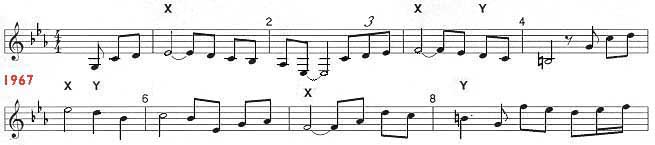

Browser-resolution willing, here are some Repent Walpurgis openings written out in notation (thanks here to long-time PH fan Linda Clare). Below is the 1967 original, clean, simple in its construction, a four-bar phrase starting on tenor G, answered with a balancing melody an octave higher, where a more strident harmonic begins to wail in the recording. The simple, hummable tune (did it start life with words, I wonder?) is dignified by the stately triplet in bar two, and by various kinds of Baroque ornament.

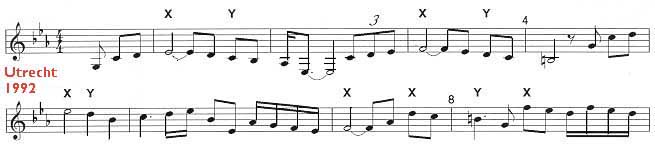

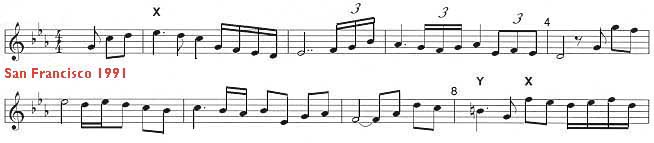

Throughout these scores Linda has used an 'X' to signify flicked 'crushing notes' (posh players call them acciacciatura or appoggiatura) and rising 'slides' (ditto, Schleifer); and a 'Y' is intended to represent various highly-characteristic Fisher turns and mordents. For aural clarification, use the original recording and check out the 'X' on the fourth note of the example above, and the 'Y' on the second note of bar five.

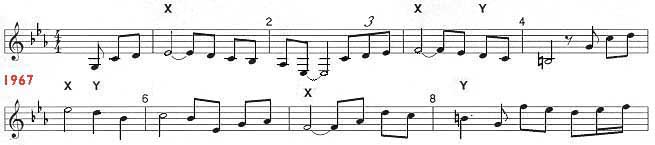

Yet this is a only a simple sketch compared to the variation Matthew came out with at Easter, 1969, at New York's Fillmore East:

The ornaments are broadly the same, but bar two has grown a middle C passing-note which then persists in almost every other recording I've heard. Additional semiquaver passages and syncopations assure us that the 1967 original was not to be respected as any kind of template.

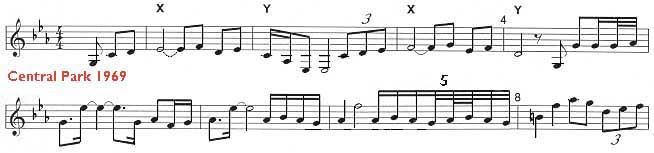

Yet this is a only mere sketch compared to the extraordinary performance recorded in Central Park, the same year:

The opening four bars present an undulating but highly-recognisable variant on the original melody: but the answering phrase is stood on its head, very excitingly and syncopatedly, with increasingly inspired and fantastical ornamentation, as elaborate in its conception as it is dextrous in its execution (just nip over to your B3s, your Farfisas and Mellotrons, and sight-read bar seven for me?). When I win a free ride in a time-machine, this taut and frenzied showing in Central Park 1969 will be one of my prime destinations.

Amazingly, August 1995 seemed to offer just that time-machine excursion: here was Matthew onstage in London playing Walpurgis as an encore of scarcely believable power (and here was me at a Procol Harum gig with my daughter, same age as I was when I heard the original, who was later to receive amiable musical encouragement from Gary Brooker in the bar).

Later on that tour my brother and I bayed for Repent Walpurgis again - strange to be hollering for something so atypical, a number lacking the words and the voice that many would argue are Procol's most individual features: Gary mockingly mistook the shouters for 'Druids', bantered that he 'didn't know that one' ... but he graciously took a back seat in the end: he knew well enough that the fans wanted to hear the composer in the spotlight.

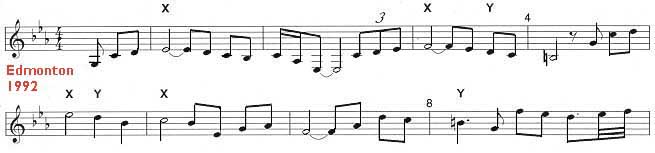

At Edmonton II, however, when the said composer was not available, Don Snow played the organ line notated below:

It sounded pretty good, in my opinion: but the interesting point is that, as Marvin Chassman points out, Snow was playing from a score. Presumably, then, what he plays must represent some sort of Platonic, ideal version of the melody, at least in the mind of the orchestrator, who I imagine was Gary Brooker. And indeed, it does adhere extremely closely - except for that extra middle C in bar two - to the melody (and the ornaments) we heard in 1967.

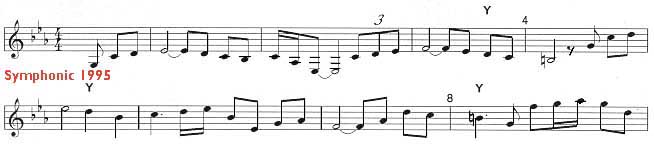

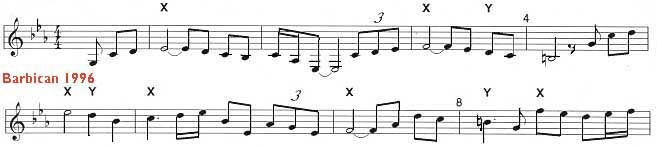

A very different 'scored' version is the Christian Kabitz orchestration as released on 1995's Symphonic recording, and heard at the Barbican recital in 1996. The lines that Matthew played on those performances (the former on the All Saints church organ and the latter on Hammond) differ only in bars six and eight: compared with the latitude in my 60s examples above, the variation is negligible.

Notice how the Barbican performance (like Easter 1969) places a triplet in the second bar of the second phrase, corresponding to the near-universal triplet in the second bar of the first phrase.

Wondering what authority this 1967-like version carried, I dropped Matthew an e-mail asking how closely he had stuck to the Kabitz. 'I glanced at the organ part,' he replied, 'and it seemed to be completely wrong so I disregarded it. I seem to remember having to modify my part so it wouldn't clash with those silly trumpet lines near the beginning.'

So if these very similar takes are not in fact following an arranger's blueprint, are we to conclude that the 90s Fisher has lost his appetite for extemporisation? A glance at the score below, from the live Utrecht recording issued on 1992's AWSoP CD, shows that it's not so:

This sticks to the 'traditional' opening, but offers a very pleasing departure in the four bars that answer it; while the score below, representing a 1991 San Francisco show, represents possibly the most unusual Walpurgis of all, in which it's the first four bars that vary, almost to unrecognisability: the tune starts an octave higher than usual and abandons the rising contour and rhythmic rigour of all my other examples.

Are there any common elements to be distilled from the examples above? Well ... the melody is always played on the organ (even in the orchestral versions, though the organ's not always a Hammond), and the first eight bars are monophonic ... but that's about it: the melodic variants start after a mere six notes: the variants in rhythm after three!

If the Kabitz version is 'wrong' in the composer's eyes, then what constitutes 'right', especially in view of the rich variety of mutations noted above? When I contacted him, Matthew Fisher commented (not a propos of this comparative survey, which I had not then mentioned), 'To be honest I can't remember exactly what I played on any particular version. I just play whatever I feel like doing at the time.' It is delightful and reassuring to know that the 'right' answer is such a musically instinctive one, reflecting the primacy and freedom of the performer.

If you can bear any more of these pedantic antics, stay with me and with the above eight performances, as we widen the scope of this very local enquiry to ask what formal global structures Repent Walpurgis appears to exhibit in performance.

The most obvious structural feature would seem to be the inclusion of the delicate and academically-accurate piano-episode sandwiched between the two raucous bouts of ensemble improvisation. 'We'd like to finish off with Matthew's - may I say "classic"? - may I?' proclaimed Gary Brooker at the Fillmore East in 1969, to shouted replies of 'Yeah!' In a 1990 Norwegian radio interview with Niels-Erik Mortensen, Gary explained how this 'classic' arrangement came about:

'Yeah, well, Matthew Fisher had written a theme, um, which was very nice, and I thought "We can't keep going through that," and at that time I think I'd just learned the Bach Prelude - to my great satisfaction - and I said, "Um, what about sticking this bit in, Matt?" And he said, "Yeah, alright".' This laconic doctrine belies the artful fashion in which the alternation of minor / major / minor keys works on our emotions!

Paul Williams in his seminal 1967 Crawdaddy! review of the first Procol album described Repent Walpurgis as '... the most effective rock composition yet to utilize classical music influences.' Certainly it is unusual in its long, unironic and unadulterated Baroque quotation, which now seems so intrinsic to its impact. We could imagine She Wandered Through the Garden Fence without its bit of Jeremiah Clarke, and Kaleidoscope without its Holst; later Procol tunes like Skip Softly, Grand Hotel, TV Ceasar and Bringing Home the Bacon have grown and then shed various 'classic' addenda, but they're all numbers that work perfectly well without them. Not so Repent Walpurgis.

It's not even like the other huge instrumentals (Grand Finale, Stoke Poges, 'Albinoni', the Blue Danube) that the band has featured, in that it's fundamentally a four-chord trick; its closest Procol parallels (blues tracks excepted, of course) might be the coda of Pilgrims Progress or the Simple Sister interlude - also sections that derive their effect from local contrast.

But while its Bach has remained, Repent Walpurgis has seen other 'classical' tangents come and go - most consistent has been the Tchaikovsky quotation (from the opening of the First Piano Concerto) which sellotapes the end of the Bach on to the rest of the ensemble work-out; latterly there's been a rhythmical motif from Beethoven's Fifth Symphony that you can clearly hear on the Utrecht recording starting at 3 minutes 52; there are now even very un-rock scalar passages tumbling down Gary's piano after the Bach. But these are only grafts on to the structure, like Christian Kabitz's Gounod-like soprano floating over his harping Bach prelude: they are all more-or-less ironic quips, done because they fit, not because the piece is crying out for them.

The tables below show the approximate speeds (beats per minute) and durations of the versions whose openings were discussed above; they also aim to show how many 'rounds' of the four-chord sequence are played before and after the Bach prelude, and, below that, to give a brief account of the instruments and motifs active during those 'rounds'.

|

1967, the black album 4 minutes 56 at 68 b.p.m |

Intro / 9 rounds / Bach / 6 rounds / 35 seconds outro 1 round of BJ's drums; 2 rounds organ melody; 2 rounds organ on two manuals; 1 round detached chords; 4 rounds Trower guitar solo; 12 bars Bach piano; 1 round 'Tchaikovsky'; 1 round solid chords; 3 rounds guitar solo; 1 round high notes; 35 seconds of chords with BJ drum frills and fills. |

To my ears this is the matchless master-version: Robin Trower's modal line wells up and escapes from the churchy backing, his solos are beautifully reasoned, and the Bach presents a plateau of momentary resolution before the harmonic tussle is resumed. The guitar melodies are singable but not easy to remember, and fitting without seeming predictable; as the far-sighted Paul Williams wrote: 'Repent Walpurgis ... is one of the finest instrumental tracks in rock. It will move you, in a rock sense; it will, in fact, shake you mercilessly, and leave you aching to hear it again.' (More about Trower's Walpurgis playing here).

|

Fillmore East NYC Easter 1969 6 minutes 38 |

Intro / 9 rounds / Bach / 8 rounds / 86 seconds outro 1 round BJ's drums; 2 rounds organ melody; 2 rounds organ on two manuals somewhat like original; 1 round ensemble chords, Trower guitar bubbling under; 4 rounds guitar cutting loose; 12 bars Bach with piano and a trace of guitar; 1 round 'Tchaikovsky'; 1 round solid chords; 6 rounds guitar solo over exciting racket; 86 seconds chords with drum frills, lackadaisical at the end, with an unsatisfactory multiple swipe at the final chord like an executioner taking ages to get the head off Mary Queen of Scots. |

A comparison of the proportions of the original recording with those of the Fillmore performance, above, confirms the common-sense conclusion that this piece had no fixed length; but those extra couple of rounds after the Bach seem to throw out the proportions of this version, which sounds as if it has lost its way, and lacks that sense of emotional inevitability in the placing of the climax: at the end bombast has triumphed over art. It sounds exciting, but probably no more moving than Stoke Poges, which is certainly not the case with the original recording. There may, of course, have been very good local reasons for this: I wasn't there, and I don't know exactly what 'fruit and nut' the musicians had been enjoying before the piece started!

Gary also sounds unpromisingly off-net in his Central Park introduction - 'We'd like to play this last number for special people and even ... special people; this one is always our closing number. Matthew wrote it, and we're all going to play it ...' - and yet the performance that follows is dynamite ... slow, slow dynamite. By comparison with the Walpurgises that Procol took on the road, the original recording set an almost sprightly pace, though in its vinyl context it seemed daringly ponderous at the time.

|

Central Park 1969 7 minutes 23 |

Intro / 9 rounds / Bach / 9 rounds / 101 seconds outro 1 round BJ's drums; 2 rounds organ with very fancy ornaments; 2 rounds organ on two manuals, unlike original and including 'ducking' semitone figure; 1 round detaching chords; 4 rounds Trower guitar cutting loose; 12 bars Bach piano; 1 round 'Tchaikovsky' (understated); 3 rounds solid chords with guitar slowly emerging; 4 rounds guitar solo, rapid; 1 round high notes slowing down; 101 seconds of final chords with drum frills tantamount to a solo before the last chord. |

Here the second half of the tune is even longer that the Easter variant; yet to my ears it never loses interest for a moment. The piece may be 'always our closing number' simply because its impact is hard to follow (except with an outright basher like Whisky Train or an aural icon like AWSoP) - and it can safely be trotted out even when the Brooker larynx has taken an evening's thrashing: it feels all wrong to encounter it near the start of the Easter Island bootleg, or far from the end of The Symphonic Procol record.

|

SF Palace of Fine Arts 1991 7 minutes 17 |

Intro / 9 rounds / Bach / 7 rounds / 79 seconds outro One minute of drum introduction; 2 rounds organ melody very unlike original; 2 rounds organ on two manuals quite like original; 1 round detached chords; 4 rounds Renwick guitar cutting loose; 12 bars Bach with piano and organ and bass prominent; 1 round 'Tchaikovsky'; 1 round solid chords; 2 rounds guitar solo on top; 2 rounds solo with rising scale in bass; 1 round high notes; 79 seconds of chords with drum frills. |

The 1991 version, above, sounds to me like a hastily-convened, perhaps unpremeditated encore: the lengthy drum introduction perhaps covers other players' unreadiness, and the octave-transposition of Fisher's organ-entry may conceivably have been unintentional. This performance is taken faster than the live 60s versions under discussion, but overall the number is not reverting to its vinyl proportions. The rising-scale motif has evolved now, and it is found again in the gigantic Utrecht performance, a near-favourite of mine although Geoff Whitehorn's mercurial style is worlds away from the measured Trower original. At this stage Gary's rhythmical homage to Beethoven's Fifth has emerged: this 'classical' joke may have contributed to the extended second half:

|

Utrecht February 1992 7 minutes 40 |

Intro / 9 rounds / Bach / 11 rounds / 82 seconds outro 1 round drums; 2 rounds organ melody very like original until bar 6; 2 rounds organ on two manuals with semitonal figure fully developed; 1 round ensemble chords; 1 round Whitehorn guitar bubbling under + harmonics; 3 rounds guitar cutting loose; 12 bars Bach with piano faintly faltering; 1 round 'Tchaikovsky'; 1 round jangling piano chords; 2 Beethovenesque rounds on piano; 4 rounds guitar solo on top with Bronze bass excitements; 1 round solo where rising scale starts; 1 round bi-manual footling; 1 round high notes; 1 minutes and 22 seconds of chords with Brzezicki drum frills. |

That word 'classical' (which has numerous conflicting 'meanings' in academic music) is often used as a synonym for 'orchestral': and from that standpoint one might expect Repent Walpurgis, with its excerpt from the 'respectable' repertoire, to be well-suited to an orchestral treatment:

|

Edmonton II 1992 7 minutes 16 |

Intro / 9 rounds / Bach / 10 rounds / 80 seconds outro 1 round Wallace drums; 2 rounds Don Snow organ melody; 2 rounds organ on two manuals very like original; 1 round ensemble chords ; 1 round Whitehorn guitar bubbling under; 3 rounds guitar cutting loose; 12 bars Bach with soprano and piano; 1 round 'Tchaikovsky'; 1 Beethovenesque round on piano; 2 rounds trumpets, + choir singing organ melody; 2 rounds guitar solo on top; 2 rounds solo in which rising scale starts; 1 round bi-manual footling; 1 round high notes ; 80 seconds of chords with drum frills |

The Edmonton II version sounds well enough, but to my mind the power of this number resides in its Sisyphean retreading of the same tortured chords and their anguished exploration by the guitarist: I'm not sure that there's much of a frisson to be derived from extra brass business or from the pseudo-classical re-emergence of the opening organ theme as a choral line after the Bach has passed.

Better that Edmonton II arrangement, though, than the stagnant orchestration that appeared on The Long Goodbye album, a performance drained of all passion, in which the return of Robin Trower is pretty disappointing. In the vibe-free calm of the dubbing studio his solos came out bitty and inconsequential: for my money this version could have said 'goodbye' a good deal sooner.

|

The Long Goodbye 5 minutes 34 |

Intro / 10 rounds / Bach / 6 rounds / 31 seconds outro 1 round impetus-free timpani rolls; 2 rounds church organ melody not unlike original; 2 rounds organ with brass interrupting the two-manual tunes; 1 round sprightly chromatic three-note organ phrases; 1 round adding strings, Trower guitar bubbling under; 4 rounds guitar cutting loose; 12 bars Bach with soprano (not like Edmonton II) and harp, + celestial organ joining in; slowing down for 2 rounds 'Tchaikovsky'; 2 rounds running quavers on organ, guitar entering after 4 bars; 2 rounds full orchestra and choir with guitar; 31 seconds of chords with guitar and Brzezicki drum fills. |

In another e-mail Matthew Fisher commented, 'Apart from the fact that the [Kabitz] arrangement is spectacularly ineffective (compare it with Simple Sister, Butterfly Boys or Can't Turn Back the Page), my overwhelming objection was that the guy seemed to have completely missed the point. It ain't called Repent for nothing! It should have been dripping with torment, angst and things of a generally disturbing nature. Instead it just sounds pompous.'

Given the superlative arrangement that Matthew executed for his own Wreck of the Hesperus, it would be a dream come true to hear his orchestral 'dripping torment' to Walpurgis. But Kabitz was 'in the can' before Matthew came into the project, as he explains: 'I suddenly got a message from Kellogs explaining that Gary was half way through recording a 'Symphonic Procol' album and that they'd recorded an orchestral version of Repent which they'd like me to play on. If they'd contacted me before the recording I would like to have had a go at arranging it myself. I could hardly have done a worse job!'

|

The Barbican February 1996 5 minutes 48 |

Intro / 10 rounds / Bach / 6 rounds / 31 seconds outro 1 round timpani rolls; 2 rounds Hammond melody not unlike original; 2 rounds organ with brass over the two-manual tunes; 1 round sprightly chromatic three-note organ phrases; 1 round adding strings, Whitehorn guitar bubbling under; 4 rounds guitar cutting loose; 12 bars Bach with sopranos (not like Edmonton II) and harp, + celestial organ joining in; slowing down for 2 rounds 'Tchaikovsky'; 2 rounds running organ quavers not same as TLG, guitar adding in; 2 rounds full orchestra and choir with guitar; 31 seconds of chords with guitar and Spinetti drum fills |

On the other hand the same arrangement sounded much better under the live baton of Nicholas Dodd (see above): the adrenaline of the occasion extracted some excitement from all the players, especially the ever-uninhibited Whitehorn: 'Repent, that's always a good laugh,' Geoff commented in Shine On, Summer 1996. 'Play what you want; stop when you've had enough!' Such flexibility is evidently feasible only in the band-only version of the song, of course: your witness, the identical proportions and spookily near-identical length of the live and recorded symphonic versions examined above.

So, just as we found with the opening organ statements, there's a huge overall variety here: the only irreducible elements remain utterly obvious ones: that Repent Walpurgis is always slow, in common time, with that C minor / A flat / D minor seven flat five / G chord-sequence; it starts with drums, has the Bach prelude as its sandwich-filling, and people always start to clap in the 'wrong' place at the end.

Further examples could no doubt be adduced to this article: I have not looked at any Chris Copping performances, for example: readers may like to choose their own examples. But enough Walpurgatory pontifications; let's remember, symphonic pretensions notwithstanding, that what we are dealing with here is rock music, music of the instinct, of Matthew's 'whatever I feel like doing' - it was never supposed to be a pedant's playground.

In a postscript that Matthew Fisher added to one of the above e-mails (all quoted with permission) he generously suggested, 'Actually, I've always felt that much of the credit for this track should have gone to Rob.' Quite rightly so; and how revealing it will be if a Ray Royer recording of it ever comes to light! But nestling in that postscript was a very intriguing suggestion that Repent Walpurgis had played a crucial part in Harum history, in that Robin Trower played it for what must have been effectively his Procol audition:

'Back in 1967,' wrote Matthew, 'after the split with Bobby and Ray, Gary brought in BJ and Rob for a try-out jam session. Denny Cordell asked that another guitarist he knew also be allowed to attend. However, as soon as we ran through Repent (which Rob had never heard or played before) we knew he was the one we wanted!'

31 years on, this is surely another reason to celebrate the protean behemoth that is Repent Walpurgis! Atypically repetitive, flexible and Reidless, it nevertheless holds a unique place in the hearts of Procol followers. And I have to declare: if you told me that Procol Harum were convening to play a single request, and then disbanding for all eternity, Fisher's Repent Walpurgis is the anguished thunder I would be hoping to hear.

|

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |