'Taking Notes and Stealing Quotes'

The Thin End of the Wedge

This wonderfully alarming and unexpected song presents a miraculous marriage

of words and music. It could surely not be mistaken for the work of any other

artists, yet at the same time paradoxically it presents a developmental

cul-de-sac in the Brooker / Reid canon. Astonishingly it seems to have attracted

almost no critical attention, and, where it has, this has not been favourable,

for example the slightly-mystifying 'There remains still a tendency to use music

as an intensifying experience within Procols sound as evidenced by the

neurotic, squirrel-paced jibberings of The Thin End of the Wedge.'

(Michael Sajecki in Shakin' Street Gazette).

Verbally this must be Keith Reid's sparsest recorded piece, so

impressionistic and pared-down that it is hard to conceive of his writing it in

isolation and mailing it to Gary 'in a packet' to be set to music. One suspects

that The Thin End of the Wedge may have arisen when he was pressed to

come up with words 'to order' in the studio, perhaps to fit a piece of music

that was developing while other numbers (maybe The Poet / Without a

Doubt) failed to work out. In any event the text is fascinating in its

starkness, and the nightmarishly heavy performance it receives (its weight oddly

not compromised by the virtual absence of BJ) is entirely fitting.

This song has a harmonic kinsman in A Salty Dog, inasmuch as it

ventures where surely no pop music has gone before. Its piano/guitar

parallel-octave quaver-runs carve a contour seemingly related to be-bop,

especially where the penultimate bass note is a semitone above the root; above

this we hear heavy note-clusters inflected with jazz discords, but thundered out

with a most unswinging gravity. When the four-bar phrase transposes upward for

its reiteration, it's not by the blues interval of a fourth, but by a bizarre

and unsettling tritone, regarded in the 'serious' world as the ugliest interval,

sometimes called diabolus in musica the devil-interval. Gary Brooker

manages to make the transition from C minor into F sharp minor sound 'right',

and its mirror-image back into C minor likewise: whereupon he throws in a

handful of transitional chords, topped with uneasy instrumental seesawings,

before launching into a chorus of sweeter harmonies, unpredictable and

melody-led in his 'naive' style such as we find in the middle of Broken

Barricades. This chorus is marked by a transition to diatonic chords, with

'classical' non-root bass notes; shining organ suffuses the upper range, guitar

offers us counter-melodies, and vocal harmonies break out: but none of this

lasts long, and soon the mogadon bebop gets going again in yet another key

while Copping's brooding organ squats unchanging above it

then the whole

nightmare begins afresh.

This track is radical in that it has no conventional drumming. Far back in

the mix lies an intermittent, industrially-treated offbeat that probably

emanates from a ride cymbal, and in the playout, amid the tumult of electric

piano and the vocal screaming, we hear the patter of a muted tom-tom. But

everything else is working overtime to compensate: the guitar sound achieves

terrific saturation, the bass is played and recorded with incisive force (Alan

Cartwright evidently plays his Fender Jazz bass with a pick!) and the vocal

performance is fantastic as is the simple conception of the rising tessitura

as the 'got the' lines pile up too. The final chord is an E flat over an F bass,

hanging unresolved until Monsieur R Monde clears the air with a fresh

start

but then that song is left hanging too. Unquestionably Chris Thomas's

debt to Phil Spector pays off in The Wedge, in the sheer sonic weight of

the ensemble; the song is so unconventionally voiced that we really don't expect

to hear clear separation of instruments. If this is the way his work with Procol

Harum was going, it seems a shame that 'Tommy' was not retained to lend some

substance to the likes of The Final Thrust, and some due drama to The

Piper's Tune.

Could the heavy sound of the record, and its multiple vocal parts, possibly

be reproduced live? Certainly the song was part of the setlist during the

one-month American tour (April May 1974), but it did not long survive the

promotion of the Exotic Birds album. In Copenhagen on 28 November (where

Gary declared he'd written the song 'specially for Denmark') it almost went with

a swing, propelled by BJ's full-fledged drumming, and had grown an exciting,

even more dramatic interpolation (mp3 here) and

gathered some alternating C minor and F chords amid the riffing. These new

features were also heard two days later in Oslo, where there were effective

vocal harmonies and some onstage screams too. It would be fair to say that The

Thin End of the Wedge underwent more development than other songs from the

album, and this may be because the band felt so confident with the quality of

the composition: 'I love that Thin End of the Wedge,' Mick

Grabham told BtP, '

It's always been one of my favourites.' This may have

been partly why the song was resurrected for the faithful when the nine-man

Harum played for fans at Redhill in 1997: here

the antiphonal vocal saw some unexpected variation, and the beginning presented

some problems of unfamiliarity: Gary introduced it (mp3 here)

as 'probably the most horrible' of all the songs the band had ever done, though

once it was played successfully he admitted he had always thought that was

'quite a pretty little song'. After the gig it was said that Procol had taken a

while to rediscover a particular chord (Chris Copping had FAXed a preliminary

MIDI score of it up from Australia)

but they had been even less prepared

five years earlier, when they had tried out The Wedge at the New York's

Academy of Music on 19 May 1992: Gary began, 'I don't know what's gonna happen

with this. This is one we haven't actually played ... just run it up the

flagpole in rehearsal'. New boys Whitehorn, Bronze and Snow coped well with the

arcane changes, but Mark Brzezicki started out with Carmina Burana drum-bashery

which gave way to a somewhat metronomic slog throughout. The words did not come

to mind easily, especially in the chorus, and the 'picture-story' shout-ins

eventually gave way to soul-man declamations of the title-phrase (mp3 here);

the stand-out feature was Geoff Whitehorn's unprecedented solo (mp3 here).

It's certainly a demanding song to play: there's nothing conventional here, no

hope of allowing finger-memory to help out if concentration slips; the demanding

ensemble riffs, though not fast, will expose any anomaly instantly as was

revealed in Guildford by the (admittedly amateur) Palers' Band, surely the only

ensemble ever to attempt to cover The Wedge while the vestigial

narrative must make the words among the hardest in Procoldom to recall.

These words are quite radical in Reid terms. A great proportion of the lines

begin with 'Got the

' and seem to add up to a litany of 'desirables' for a

fan of B movies; however the 'got the' lines in the chorus shift their focus to

'undesirables', listing what seem to be the uncomfortable or 'wrong' upshots of

some maladroit, though indirectly specified, decision. What precedes each verse

is an antiphonal recital of the rhymes from its first four lines (faintly

recalling the way that initial words of opening lines contributed the cumulative

title of In Held 'Twas in I). Both voices are Brooker's it would be

wonderful to hear this verbal tennis played between Brooker (full voice) and

Reid (whispered responses). The lines that follow appear to concern the world of

cinema, with a bias to the cheap and lurid 1960s' variety [as commemorated by

Kate Bush in Hammer Horror]. However there is no actual film entitled The

Thin End of the Wedge, and on examination the words prove to be involved in

an elaborate game of 'tag' in which the tangential associations of each line

resonate obliquely with those of neighbouring lines, further to unsettle the

thoughtful listener. Many of the words have meanings in the world of drug slang

too: the shortness of the lines does not in any way diminish their richness

(it's surprising not to find the word 'shot' in here somewhere). Taken together,

these images hint at a nightmare experienced cinematically, and in this sense

the song tallies with other numbers on this album such as Nothing But the

Truth and Monsieur R Monde, as well as with the epic sweep of Whaling

Stories and The Dead Man's Dream elsewhere.

- 'Got the picture': 'get the picture?' is a mildly hectoring way of saying

'do you understand?'. This opening line could be construed as a rueful way

of implying 'I understand the way things have worked out for me', though of

course its primary meaning, in this context, is to do with cinema.

'Picture', as an abbreviation for 'motion-picture', sounds very American to

British ears (as did 'movie' at the time this record came out): it's the

sort of word uttered by Hollywood moguls and studio-hotshots rather than by

the fan in the street. Reid uses 'picture' in a variety of ways, as this

selection shows: 'Our local picture house' (Rambling On); 'Picture

... rush (and so forth)' (The Thin End Of The Wedge); 'The close of

the picture' and 'Which kills the picture' (New Lamps For Old);

'Painting the picture' (Skating On Thin Ice); 'that's the way the

picture reads' (Into The Flood); 'I've still got your picture' (One

More Time); 'Wonder where the picture went?'; (The Pursuit Of

Happiness); 'a picture through the glass'; (the unpublished Last

Train to Niagara) and 'her picture's in Vogue' (the unpublished A

Real Attitude). Other songs with a photographic or cinematic angle to

them include: 'The camera dissolves' (The Mark of The Claw); 'she

swallows the camera' (the unpublished A Real Attitude); 'I went to

see a movie' (Something Following Me); 'Our local picture house was

showing a Batman movie ' (Rambling On); 'God's alive inside a movie!

Watch the silver screen!' and 'flashbulbs glorified the scene' (Whaling

Stories).

- 'Got the rush': the 'rush' is the print of a particular scene that's made

available to the director at the end of a day's filming, 'rushed' to him or

her from the processing laboratory for speedy inspection in case any

sequence needs to be redone before the relevant sets, lights and so forth

are dismantled. In rock, however, the word also very typically alludes to

the 'adrenaline rush' following ingestion of various drugs, especially

heroin (see Lou Reed's Heroin): sundry bands named Rush have come and

gone. But 'rush' has a great numbers of other meanings, including the grassy

marsh-loving reed, robbery with violence, a sexual advance, a swindle, and a

ganging-up: to give someone 'the bum's rush' is to see them off

uncompromisingly. Some of these meanings will become 'active' in the minds

of particular listeners to the song, and will be nourished by overlaps with

associations of words later on.

- 'Got the story': 'get the story' can mean much the same as 'get the

picture'; however 'story' is the standard name for any piece of writing in

journalism, as well as referring, conventionally, to the narrative in a

motion-picture.

- 'Got the hush': a 'hush' is of course a silence, and this we might imagine

falling as the picture, or the story, begins: however 'hush-hush' means

'secret', and seems in this part-sense to relate more to the obscure frame

of reference in the chorus of the song.

- 'Got the joker': the Joker is a character in the Batman series

(name-checked in Rambling On). Primarily, however, the word refers to

anyone who plays a joke, and more interestingly to the supplementary

wild-card in a pack of playing-cards. To 'get the joker' is a boon or a

nuisance, dependent on the game; and a playing-card thread is here

established by the appearance of 'flush' following. 'Joke' is often used

somewhat mirthlessly in Reid's writing: 'though the crowd clapped

desperately they could not see the joke' ('Twas Tea-time at the Circus);

'from the proceeds of the joke' (Butterfly Boys); 'Unique

entertainment no longer a joke' (New Lamps for Old); 'It had

all become a joke' (the Brooker solo piece (No More) Fear of Flying).

- 'Got the flush': this line relates to 'joker', inasmuch as 'flush' is a

run of cards in games such as Poker. But 'flush' also relates to a suffusing

of the face with blood, such as would occur if one choked, so it links the

'joker' idea to the 'choker' one that follows. In this facial sense 'flush'

corresponds to 'make-up' in the second verse, but it is also the

characteristic verb for emptying the lavatory-cistern to dispose of unwanted

matter, and at drug-busts the police are apt to forbid such flushing in case

evidence is swept away at the same time (in this connection, note that

'Spanish Main', which occurs in Pandora's Box, is Cockney

rhyming-slang for 'drain').

- 'Got the choker': a 'choker' is not only one who chokes or is choked, but

a strip of cloth worn by women to draw attention to their fine necks. It

corresponds to 'seam' in the second verse.

- 'Got the crush': to have 'a crush' on someone is to be infatuated with

them

there's a sense in which this follows on from the feminine image in

the preceding line. More obviously, and paradoxically, both 'crush' and

'choke' are words concerned with bodily violence, and perhaps related to the

typical content of B movies. Additional meanings of 'crush' include: a soft

hat; the vagina, in lesbian slang; a

crowded room; a fruit drink such as orange crush; and as a verb 'to crush'

can be to obliterate someone's hopes and ambitions, which is a sense that

sets up the disillusioned world of the ensuing chorus.

- 'Got the wrong side of the bed': two thoughts arise on mention of the

'sides' of a bed. One relates to the idiom, 'got out of bed on the wrong

side', used when someone seems unaccountably ill-tempered or ungracious,

especially in the morning it probably harks back to folk/magical beliefs

that the right-hand side is the good path, the left-hand the path of evil. A

second response to 'side' is that the bed in question is a 'double' or

marital bed, in which some couples like to establish 'my side' and 'your

side': in this song 'got' might mean 'I was allotted', leading us to

understand 'I slept badly, having been obliged to sleep on the unaccustomed

side'; or it might have more penetrating reference to being forced to play

the wrong role in a marriage. Either way, taken with the cinematic images of

the verses, we seem to be witnessing some sort of nightmare unfolding here.

Reid's treatment of the 'bed' image in his Procol songs includes 'attacked

the ocean bed ' (A Whiter Shade of Pale); 'the lipsticked, unmade

bed' (Homburg); 'throw some light upon the gloom around our bed' (Salad

Days (Are Here Again) ); 'his bed is made ' (Good Captain Clack);

'I'm lying in my bed hatching million-dollar schemes ' (the

officially-unpublished Seem To Have The Blues (Most All The Time));

'I wasn't at home in bed ' (Juicy John Pink); 'a floor for my bed ' (Dead

Man's Dream);'shares the bed in every house ' (TV Ceasar) and

'You lie in bed alone ' (A dream in ev'ry home).

- 'Got the wrong slice of the spread': the word 'slice' can relate to a

serving of food, which is an idea supported by 'spread' when the word is

used in approval of a meal laid out on a tabletop; equally 'slice' can be

'share of the money', which tallies with 'wedge' below, and 'spread', if it

relates back to the imagery of the previous line, might invoke 'bed-spread'

or counterpane, suggesting that the narrator has not slept well, a partner

having commandeered an undue share of the bedclothes.

- 'Got the thin end of the wedge': the phrase 'thin end of the wedge' refers

to wedges used for splitting blocks of stone or wood: in idiomatic use it

alludes to large consequences following from small beginnings, often in

combination with the decline of something. 'Wedge' is a slang word for

penis, or LSD, and it is back-slang for 'Jew' (formed in the same way that 'yob'

is from 'boy); however the most significant 'other' meaning here is probably

a monetary one since, perhaps by analogy with 'wad' or even 'wage', 'wedge'

means money, particularly the 'split' or 'slice' of a deal, in which sense

it relates back to 'slice' in the previous line. It would not be surprising

to learn that this meaning related to the plaint for a fairer deal heard in Butterfly

Boys, nor that the 'picture' alluded to in the verses was related to

'end of the picture' in New Lamps for Old. This is the only line in

the chorus not to feature the word 'wrong' in its various meanings: we can

perhaps assume, by association, that this 'thin end' is 'wrong' in the

narrator's eyes too.

- 'Took the wrong bend on the edge': this line stands out as the only one

starting with 'took'; whereas the other lines present donnιs, the

present line represents a decision taken by the narrator, and it seems to

have been catastrophic. Alpine motoring comes to mind, with its bends and

edges; equally listeners will associate 'bend' with 'bender' (a drinking

spree) and to live 'on the edge' is to cultivate a life of major risks: This

Old Dog's hell-raising narrator confesses that he has 'got myself on the

edge of one hell of a losing streak'; and the questing Beyond the

Pale invites us to 'search

past the edge.'

- 'Got the picture / Got the screen / Got the movie / Got the dream': the

lines of the second verse are markedly more focused and less allusive in

their imagery. Here only 'dream' stands out as non-cinematic (though

dreaming is often likened to the showing of an interior movie, just as the

movies are one place where people can supposedly realize their dreams or

fantasies): and this tallies with 'wake-up' below.

- 'Got the make-up / Got the seam': these lines appear to allude to the

make-up and costume departments of a film-production company, yet they also

convey an uneasy sense that the narrator is dreaming he is turned-out as a

woman, with make-up and stockings, with their seams: 'flush' and 'choker',

even 'crush' all become relevant here. This might coincide with our reading

of 'wrong side of the bed' above, and would perhaps in turn promote the

waking-up, and the scream, with which this highly enigmatic song concludes.

- 'Got the wake up': 'the wake-up' is not conventional English, though

'wake-up call' might be. Here the narrator appears to be being summoned out

of his dream: we may note that this is in a sense related to the various

alarm-bells noted in other songs passim, especially Shine on

Brightly.

- 'Got the scream': as well as being an involuntary expression of terror,

the word 'scream' can be used idiomatically: 'ooh, she's a scream' might

well be said of someone who had dressed up as a woman for fun. In the

opening track of the other side of the album we hear of 'an awful gaping

scream', and other screams in Procoldom include 'I screamed on my knees in

the witness box' (Lime Street Blues); 'The man looks in my

mouth and screams' (Something Following Me); 'Sousa Sam can

only hear the screams of Peep the sot' (Cerdes (Outside The Gates Of));

'I managed to scream' (Dead Man's Dream); 'Echo stormed

its final scream' (Whaling Stories); 'screaming "There's

an eye in the middle of his head!"' (Alpha); 'The camera

dissolves a crescendo of screams' (The Mark of The Claw) and 'The

worm started screaming' (The Worm and The Tree). In view of the

repeated use of the word 'picture' in the present song, however, it may be

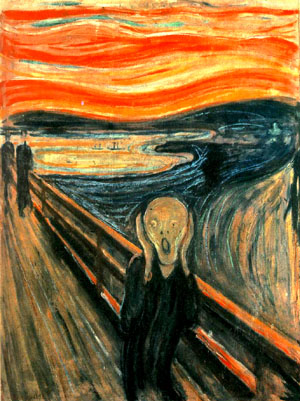

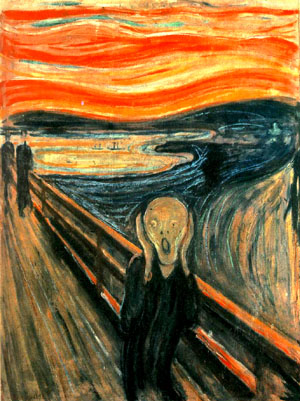

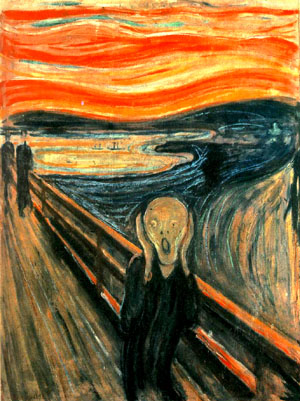

worth drawing attention to the well-known 1893 expressionist painting known

in English as The Scream (illustrated) in which Edvard Munch's

nightmarish composition depends heavily on bends and indeed on the thin

end of a wedge.

Thanks to Frans

Steensma for additional information

about this song