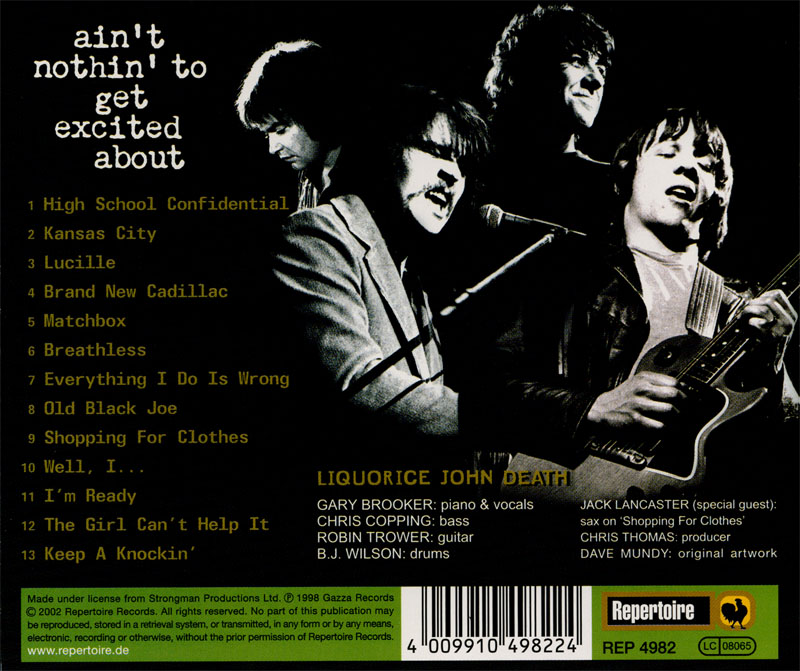

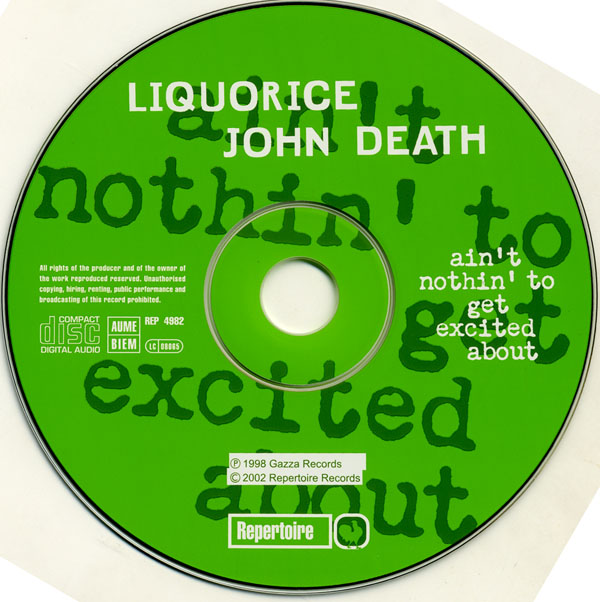

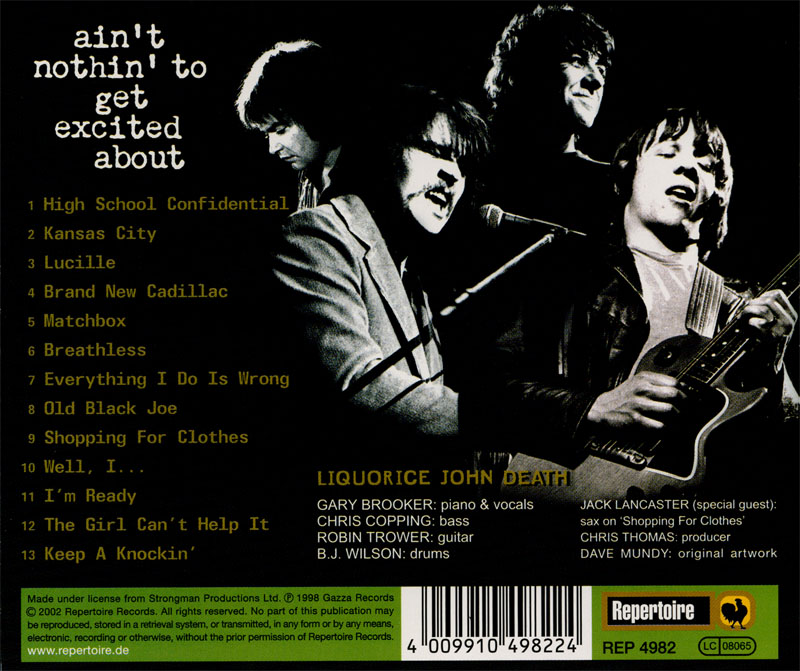

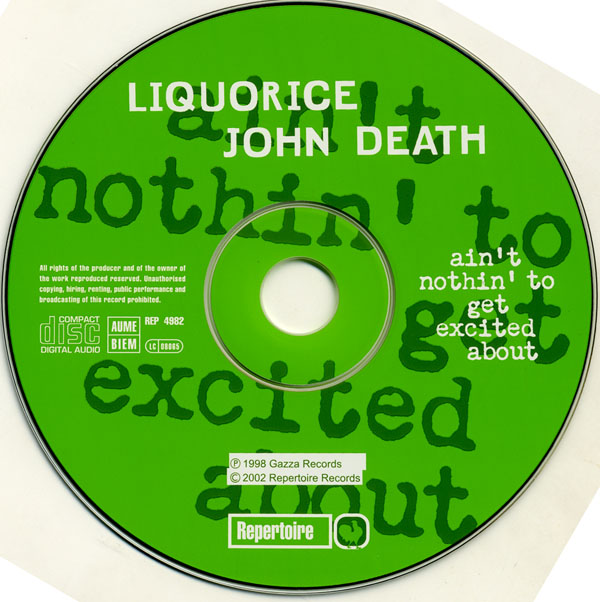

Ain't Nothing to Get Excited About

Liquorice John Death •

Repertoire REP 4982, 2002

Liner note

The

spirit of rock’n’roll permeates these exciting performances by Liquorice John

Death, a band that attained mythical status after its first brief flowering in

the early Seventies. As they blast into the hits of Little Richard, Jerry Lee

Lewis and Carl Perkins, we hear all the warmth and expertise of a bunch of

highly experienced and committed musicians.

The

spirit of rock’n’roll permeates these exciting performances by Liquorice John

Death, a band that attained mythical status after its first brief flowering in

the early Seventies. As they blast into the hits of Little Richard, Jerry Lee

Lewis and Carl Perkins, we hear all the warmth and expertise of a bunch of

highly experienced and committed musicians.

Only a few fortunate radio listeners ever heard Ain't Nothin’ to Get Excited

About. So just who are these enthusiastic rockers, who made one great record

before vanishing into the mists of time?

The answer to the riddle can now be told, following the recent rediscovery of

the original tapes. It is an intriguing tale of [sic] full of mystery and even

tragedy. While collectors and fans have long debated the origins of ‘the album

that never was’, it can now be revealed that it was the work of some of rock’s

biggest ‘name’ musicians.

London 1970 …

Gary Brooker (vocals, piano), Robin Trower (guitar), Chris Copping (bass) and BJ

Wilson (drums) are gathering at EMI’s Abbey Road studio for their latest album

session. They are, of course, the distinguished members of Procol Harum, one of

the biggest rock groups in the world. Perhaps even more significantly, they are

also former members of The Paramounts, one of England’s pioneering R&B outfits.

Ostensibly they are due to lay down the tracks for Home, the fourth

Procol Harum album, under the aegis of producer Chris Thomas. The music they are

due to create will doubtless be in keeping with the band’s hits, such as A

Whiter Shade of Pale, Homburg and A Salty Dog. And yet

something happens in the studio, which encourages them to take a giant leap

backwards to the kind of music that turned them on as teenagers.

It’s time to let their hair down and play some good old rock’n’roll …

Long before Procol Harum shot to dame with A Whiter Shade of Pale in

1967, Gary Brooker had been the singer and pianist with The Paramounts, based in

his hometown of Southend on Sea. The group, former way back in 1959, became very

successful, even supporting the Rolling Stones on tour. However, as they only

played ‘covers’, with very little original material, they ‘ran out of steam’ and

the band broke up in 1966.

Brooker then teamed up with lyricist Keith Reid and together they came up with a

sensation début hit song, A Whiter Shade of Pale, famed for its stately

Bach-like melody and surreal lyrics. Procol Harum was formed to perform the new

Brooker-Reid material and featured Matthew Fisher on Hammond organ. They went on

to achieve international success and toured the world. However, by the time the

group were due to record their fourth album, there had been a number of changes.

Recalls Gary: ‘We had a personnel change with Procol at the end of 1969. Dave

Knights (bass) and Matthew Fisher both left and Chris Copping (bass, organ)

joined. So we were replacing two people with one. Not always a good idea, but it

was worth a try. Chris was in The Paramounts back in 1961 and I suppose in

recognition of the fact that Procol Harum now consisted of all ex-Paramounts, we

were in the mood to remember the old days.

‘We

were actually in the studio to recall Procol’s fourth. Quite often, when warming

up in the studio and getting levels, instead of playing what we were intending

to record – and getting bored with it – we would just bash out a couple of

rockers.

‘Chris Thomas said: “Every time you do that it sounds great.”

‘So he booked Abbey Road studio and we went in and just started recording our

favourite rock’n’roll numbers. We staggered out at dawn, having attempted about

45 songs. We didn’t finish them all. I think the drummer collapsed half way

through with laughter or we’d forget the words. Out of that lot, Chris mixed the

13 tracks on this CD.’

Maybe the powers that be didn’t think Procol Harum should be recording a

rock’n’roll album at that stage in their career, even under a pseudonym. Or

perhaps it was felt that Liquorice John Death wouldn’t receive the

attention it deserved. Maybe it was simply due to carelessness that, once

completed, the precious tape vanished from the band’s possession.

Gary: ‘At some point shortly after we’d done it, Roger Scott the Capital Radio

DJ heard about the recordings. Our management at the time gave him a

quarter-inch tape of the session. He played it on Capital and it caused quite a

bit of interest.’

The

London based independent radio station was then actively promoting good rock

music and the late Roger Scott was one its [sic] most respected DJs. Even he

couldn’t do more that offer ‘Liquorice John Death’ a few plays.

‘Then it all got forgotten. Over the years I tried to find the tape we’d given

to Roger, but never could. As Chris Thomas had produced the tracks, it was his

tape and he had given it to Roger Scott. He never got it back and was always

rather pissed off about that,’ chuckles Gary. ‘But it finally reappeared when we

got a box of tapes back from EMI-Chrysalis, said to contain Procol Harum albums.

‘It

took a long time to go though all the boxes of multi-tracks. One box labeled

‘Liquorice John’ actually contained Procol Harum tracks. There is a track by

Procol Harum called For Liquorice John. But the lost album had been filed

in the wrong department. It had done into the archives at EMI and could never be

found because it was logged under ‘For Liquorice John’. But it wasn’t. It was a

totally different recording. It eventually came to light at the end of

Nineties.’

‘The Liquorice John Death album has never been released before, except as

a limited edition for fans.’

It

was a delight for Gary to hear the inspired and enthusiastic performances they

had laid down so many years ago. Among the tunes played that night at Abbey Road

were the Little Richard favourite Lucille, The Girl Can’t Help It

and Keep a Knockin’. They also cut the Jerry Lee Lewis number High

School Confidential and Carl Perkins’s driving Matchbox. These are

numbers that arouse magical memories for anyone who grew up during the

rock’n’roll years.

Brooker:

‘It was all stuff that we started off playing as The Paramounts back in the

early Sixties. We often did Old Black Joe, which Jerry Lee Lewis used to

play and [sic] was hugely popular in Southend with the Paramounts crowd. Even if

I go down there now for the occasional rock’n’roll night with a few mates,

people always scream out for Old Black Joe.

Brooker:

‘It was all stuff that we started off playing as The Paramounts back in the

early Sixties. We often did Old Black Joe, which Jerry Lee Lewis used to

play and [sic] was hugely popular in Southend with the Paramounts crowd. Even if

I go down there now for the occasional rock’n’roll night with a few mates,

people always scream out for Old Black Joe.

‘There is something about the passionate Gospel style beginning. Then it just

starts thumping and everybody goes mad. Shopping for Clothes was another

favourite. It was one of The Coasters’ strangest numbers and a hard one to do.

But I had a lot of fun, trying to do both voices. I was trying to sound like I

was five foot two tall one minute and six foot seven the next!’

In their Southend days The Paramount [sic] used to play at many different

venues, but their favourite was a club called The Shades, situated on the

seafront. It was a coffee bar owned by Robin Trower’s father. Gary recalls it

had a fabulous jukebox stuffed with classic singles. It wasn’t’ just the

musicians who loved rock’n’roll of course. One of their biggest fans was a

Southend lad called Dave Mundy. It was Dave who came up with the unusual name

Liquorice John Death’.

Gary: ‘Dave Mundy was a huge Bo Diddley fan and a bit of an eccentric. He wore

drape jackets, had a huge hairstyle and drove a great big Ford V8 Pilot car. He

was Mr Rock’n’Roll and he loved The Paramounts.

But

he always said we should be called ‘Liquorice John Death and His All Stars’. He

didn’t like the name ‘The Paramounts’ and said it wasn’t rock’n’roll. I agreed

with him. It was a name given to us by the manager of a ballroom, who was also a

champion ballroom dancer. It was even given to us in a ballroom after a talent

contest. Dave Mundy was quite right in thinking it wasn’t cool. But despite his

suggestion, we never changed our name.’

Eventually the name was used to adorn this very album, but in rather tragic

circumstances. Gary explains that Mundy suffered from severe mental problems.

‘He was so eccentric he used to spend a lot of time inside a mental hospital.

Now and then, one of the band members would go along and sign him out, so that

he could come and see us. He was so enthusiastic he even designed an album

cover, giving us the name ‘Liquorice John Death’.

One day in 1972 he got out of the asylum. He couldn’t find anybody he knew and

he jumped off the top of a 15-storey building in the middle of Southend. The

song on the Procol Harum album Grand Hotel called For Liquorice John

is dedicated to him. That’s what it’s all about when we sing ‘He fell from grace

and hit the ground’. So it is only right that he gets a full credit and the

story is finally told.’

After his death, Mundy left all his possessions to Robin Trower, including his

last will and testament. ‘It was totally bizarre. We found the album cover he

had designed and painted. So, when we found the tapes and wanted to put them

out, there was no alternative. We had to use Dave’s idea and his album title

Ain’t Nothin’ to Get Excited About, as our tribute to Dave, because he was a

great guy.’

When the ‘Liquorice John’ tape box came finally back, it meant that at last the

world could hear the long lost record. But all that Gary could find inside the

box was a quarter inch copy. The 15-inch master [sic] had long since

disappeared.

‘All that remained was the copy given to Roger Scott. It sounds fine to me and

the quality is very good. The whole point is that the music is in a totally

different style from Procol Harum. It’s the same guys but this is NOT a Procol

album. Incidentally, Jack Lancaster the sax player pops up on Shopping for

Clothes. I think he arrived at two o’clock in the morning. He was around at

the time, playing with Blodwyn Pig and lived not far from the studio.’

Listening to the tracks once again, Gary cannot conceal his pleasure. ‘There are

some real crackers on there. What I think is particularly impressive is some of

Trower’s guitar work and the drumming is absolutely amazing. It was all whacked

out ‘live’ in the studio, with no overdubs. I think any blues player could learn

a thing or two from Robin’s version of Kansas City and he plays

fantastically well on Matchbox, which was always part of our repertoire.

The solo on Lucille is absolutely mind blowing.

Brand New Cadillac

was a song by Vince Taylor, who I met once and saw play. He ended up in France

after his initial success in England. I don’t know why we faded that track out.

We still play it now and it always starts off with a great guitar riff. Then it

slows down at the end and gets louder and louder. Maybe we forgot that was how

it ended when we did it in the studio. Maybe Chris Thomas made some decision and

faded us out. Sometimes we went wrong or started laughing.

‘When we rediscovered the tape, we wondered if it still stood up, and it does. I

think it’s not so much the content as the performances. It’s the way people are

playing on this album that makes it great it’s finally out.’

Chris Welch: London, England June 2002

More Procol Harum on record |

More Liquorice John pages

The

spirit of rock’n’roll permeates these exciting performances by Liquorice John

Death, a band that attained mythical status after its first brief flowering in

the early Seventies. As they blast into the hits of Little Richard, Jerry Lee

Lewis and Carl Perkins, we hear all the warmth and expertise of a bunch of

highly experienced and committed musicians.

The

spirit of rock’n’roll permeates these exciting performances by Liquorice John

Death, a band that attained mythical status after its first brief flowering in

the early Seventies. As they blast into the hits of Little Richard, Jerry Lee

Lewis and Carl Perkins, we hear all the warmth and expertise of a bunch of

highly experienced and committed musicians.  Brooker:

‘It was all stuff that we started off playing as The Paramounts back in the

early Sixties. We often did Old Black Joe, which Jerry Lee Lewis used to

play and [sic] was hugely popular in Southend with the Paramounts crowd. Even if

I go down there now for the occasional rock’n’roll night with a few mates,

people always scream out for Old Black Joe.

Brooker:

‘It was all stuff that we started off playing as The Paramounts back in the

early Sixties. We often did Old Black Joe, which Jerry Lee Lewis used to

play and [sic] was hugely popular in Southend with the Paramounts crowd. Even if

I go down there now for the occasional rock’n’roll night with a few mates,

people always scream out for Old Black Joe.