PROCOL’S

PROGRESS

PROCOL’S

PROGRESS

Procol HarumBeyond

|

|

|

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |

|

Liner note by Roland from BtP • September 2018

This Esoteric 3CD package is filled with Procol Harum music from 1975: Disc A features the Procol’s Ninth album, with earlier studio versions of all its eight Brooker/Reid originals; Disc B contains a live US show from October 1975; and Disc C contains a British concert recorded some six weeks later. This commentary deals first with the studio album, song by song, with notes about early versions and live performances where applicable. Thereafter the ‘legacy’ songs – live versions, from Discs B and C, of numbers not on the 1975 album – are briefly considered, aggregated in chronological order of their vinyl release.

Reviewing Procol Harum’s new album on 16 August 1975, Billboard found it ‘their best and most commercial set since A Salty Dog’. Extensively publicised, Procol’s Ninth entered the Billboard Top 200 on 23 August at No 185, only to stall at No 52: this essay looks at possible reasons for its indifferent career.

For all its roster of strengths, few fans rate Procol’s Ninth their favourite Harum album. That accolade goes most often – and despite its quota of flaws – to the aforesaid A Salty Dog (1969). The two albums, representing different decades and having only two musicians in common, nonetheless share particular similarities: the multiple composers; the juxtaposition of elaborately-produced numbers with items whose treatment sounds somewhat cursory; the frequent additional instrumentation; and the wide variety of styles (Billboard reckons the Ninth spans ‘rock to jazz to blues to soul to a tinge of classical’). Also, as fans have noted, both are third albums from successful line-ups – which never recorded together again.

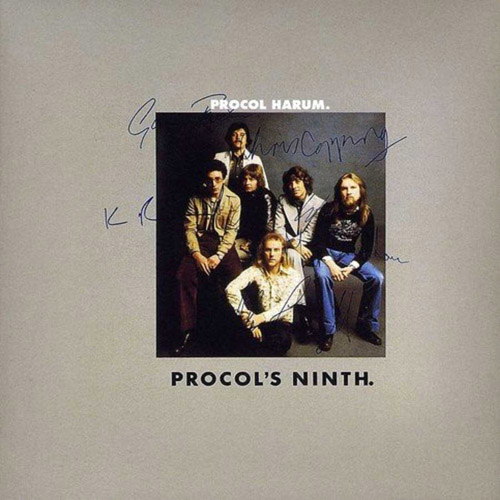

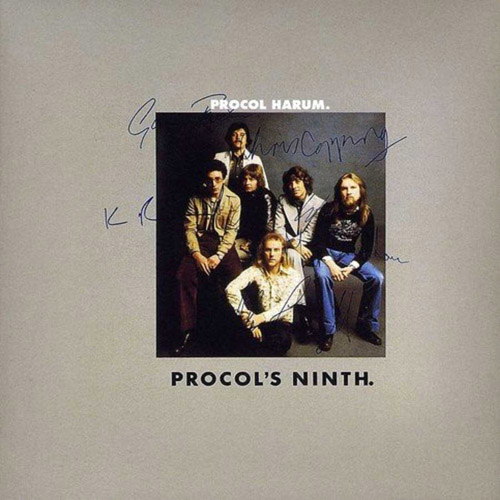

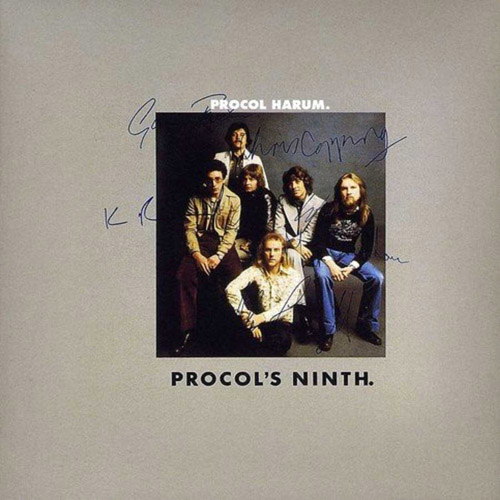

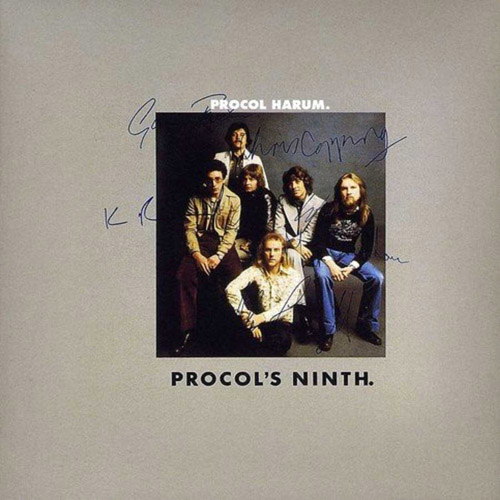

Three albums was quite a span in Procol line-up terms. From their earliest months they’d profited from incoming players’ fresh perspectives, and sailed on through personnel changes. For seven years or more they’d traded on high-quality writing and performance, rather than any promotion of personalities: if album sleeves depicted the musicians, they were cartoonified, posterised, or depersonalised by formal attire.

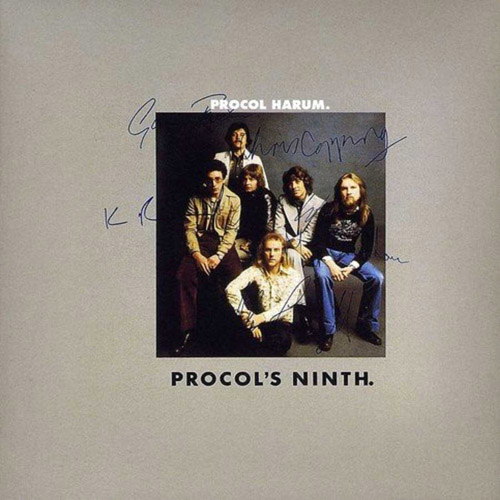

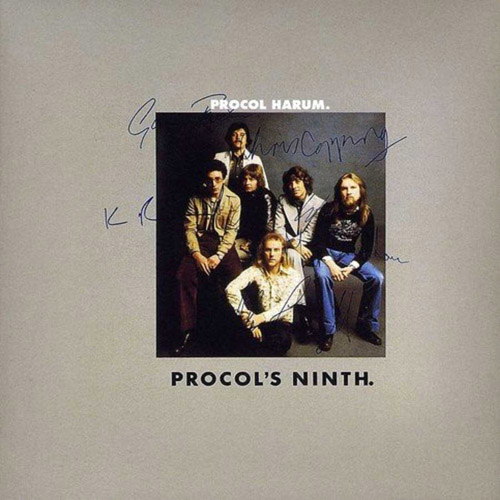

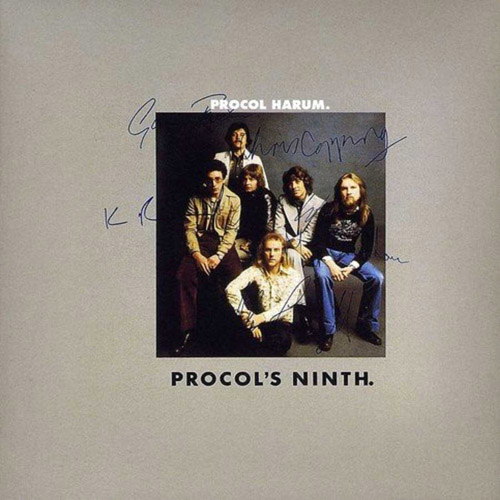

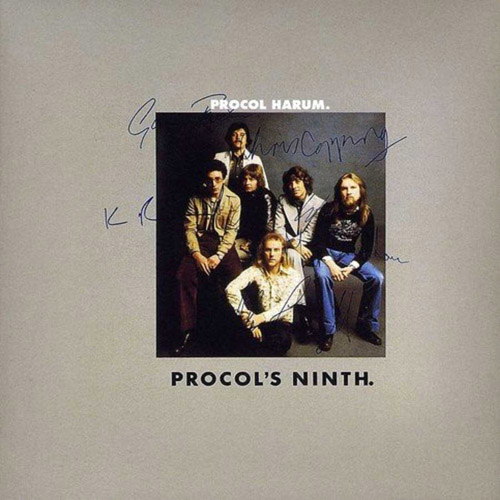

Then something changed: Procol’s Ninth was their first album with a naturalistic group shot on the cover. The printed signatures – Gary Brooker (voice and piano), Alan Cartwright (bass), Chris Copping (Hammond organ), Mick Grabham (guitar), Keith Reid (words) and BJ Wilson (drums) – drew new attention to individuals; a far cry from the Salty Dog artwork, on which just one Procoler (a non-performer, to boot) gurned alarmingly, in disguise, parodying a tobacco advertisement (‘trying to act the hero’s part’ as lyricist Reid confesses on Track A-03).

The Procol’s Ninth portrait (by fashion-photographer Terence Donovan’s then assistant James Cotier, who shared Procol’s Southend origins) is mainstream, conformist: ‘What were we, the Bay City Rollers?’ Grabham laughs now. The back illustration – Mick remembers posing in ‘a disused water-tower near the Thames’, though Brooker declares it was ‘somewhere like Itchycoo Park’ – is more engaging, but both sides lack the confidence and eccentric charm of earlier covers.

The title, likewise, feels more prosaic than, say, Broken Barricades or Shine on Brightly. Admittedly ‘Procol’s Ninth’ is jokey (adorning the band’s eighth studio album) and cheeky, inviting comparison with a cornerstone of High Culture, Beethoven’s Ninth. But the joke lands awkwardly, since the music owes little to the ‘classical’ influence previous albums had drawn on, paying homage instead to magisterial influences from the band’s own lifetimes. Classical aficionados spotted that Beethoven, Bruckner, Dvořák, Schubert and Vaughan Williams had all notched up nine symphonies … but no more. Considered alongside two songs about the travails of writing, and two more penned by outsiders, this felt ominous: was Procol’s well of inspiration no longer ‘on fire’?

Talking to the players now, one senses a certain ambivalence about Procol’s Ninth, in its own terms and in relation to Grand Hotel and Exotic Birds and Fruit, its high-achieving forebears. Its songs featured relatively thinly in 1975 concerts, though Procol’s zest for earlier material was undimmed, as Discs B and C show. So what was the studio situation underlying the creation of this somewhat anomalous record?

******

‘Leiber & Stoller to produce Procol Harum,’ was the surprise news from New Musical Express on 5 April 1975, three weeks after its report that the band was ‘rehearsing material for a new album’. Gary Brooker had indirectly owed his first chart success (1964’s Poison Ivy, with The Paramounts) to these veteran American writers, whose Bad Blood and Kansas City had also been in his early Sixties repertoire (the Paramounts added Youngblood and Santa Claus is Back in Town for their once-off reunion in Southend-on-Sea, 2005). The Coasters, The Drifters, Elvis and many more had taken Leiber/Stoller songs up the charts too, of course. By 1975 (when Gary admitted, introducing Track C-09, that he’d been surprised Leiber & Stoller ‘were still going’) they’d become sought-after record producers – Stuck in the Middle with You was their 1972 hit for British band Stealers’ Wheel (feat. Gerry ‘Baker Street’ Rafferty).

Procol Harum and long-time producer Chris Thomas had felt ‘in a bit of a rut,’ according to Keith Reid, ‘going to the same studio at the same time of year’, and the band were seeking fresh ears in the control room. Chrysalis, their record label, had arranged a meeting between Procol and the Canadian Bob Ezrin (producer of Aerosmith, Alice Cooper, and Lou Reed’s Berlin (1973) which BJ Wilson had played on) but according to Keith ‘we decided not to work with him.’ ‘I wasn’t disappointed,’ Mick adds. ‘Wouldn’t have fitted at all.’

And so it was that Procol went into The Who’s Ramport Studios in Battersea, at the end of March, with Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. ‘They were very business-like, as opposed to being artistically endowed,’ Brooker remembers now. ‘It was quite a strange experience, because their working methods were so different from ours.’ Gary’s oft-told anecdote – the producers say ‘We’re going to dinner,’ the band ask when they’ll be back, the producers say ‘We won’t!’ – epitomises the contrast. ‘But Procol didn’t go home at eight o’clock,’ he told me, ‘We’d stay on and get something ready for the next day, but never considered saying “Switch the machines on, we’ll record this on our own.”’ The respect and deference accorded to Leiber & Stoller – fifteen years older than Brooker and co – is summarised in Chris Copping’s words: ‘It was a thrill to meet Rock Royalty.’

According

to an interview in the Dutch magazine OOR (27 August 1975) the new album

was recorded in three weeks, weekends off, working a strict seven-hour day: ‘A

fair bit shorter than it would have taken with Chris Thomas,’ Mick Grabham

remembers. And although Brooker and Reid’s compositions arguably received uneven

attention from their producers, Procol’s Ninth did yield one

substantial, enduring hit.

According

to an interview in the Dutch magazine OOR (27 August 1975) the new album

was recorded in three weeks, weekends off, working a strict seven-hour day: ‘A

fair bit shorter than it would have taken with Chris Thomas,’ Mick Grabham

remembers. And although Brooker and Reid’s compositions arguably received uneven

attention from their producers, Procol’s Ninth did yield one

substantial, enduring hit.

******

When Pandora’s Box [A-01] was released as a lead single, Disc (2 August) found it an ‘uncommercial piece of musicianship from Procol and their legendary producers … plainly not a hit.’ Yet two weeks later it quoted Procol’s management thus: ‘When the critics are unanimous that it’ll be a miss, it must be a hit.’ Looking-glass logic, but accurate: the song rose to No 16, lingering seven weeks on the UK chart. Leiber & Stoller had delivered. ‘Pandora really stands out,’ Gary told me. ‘It’s not exactly understandable as a lyric, the music’s slightly weird as well. So where its commerciality comes from, I don’t know. It was written very early: I used to keep that secret, so we could publish it under Bluebeard Music, which handled our later stuff.’

The Procol’s Ninth press-kit (probably, like the promotional tour programme, authored by Chrysalis publicist Chris Briggs) almost revealed that secret, calling the song ‘a journey into fantasy [that] bears the cryptic Keith Reid imprint, well-stocked as it is in exotic, mythological imagery’. In fact Reid’s ‘cryptic’ leanings had by now ceded to the pithier, more universal style of the record’s other seven originals. Given the public’s evident ‘exotic, mythological’ appetite, finding a second chart single from the album might prove problematic … .

In 1967, listening to Ravi Shankar, Brooker had ‘enjoyed the monotony’ of the cycling C-B-G♯-A in a morning raga. In that year’s original Pandora, Robin Trower’s guitar repeated the sitar’s four-note figure right through each verse: ‘It doesn’t end up monotonous once you put different chords on it,’ Gary explains. That version ‘didn’t come together in the studio’, but the song was briefly revamped in 1973, as a slow, chugging number reflecting Grabham’s country influences.

It’s fascinating to hear the ‘raw’ 1975 track [A-11] before the producers layered on their ear-catching overdubs. Brass and winds were recorded in New York, but their most haunting addition was Brooker’s deep marimba line. Procol had found this huge instrument at Ramport, rented for a previous session; by the time they needed it, it was gone. Suddenly ‘everyone in the band was ringing every rental company,’ Grabham remembers, ‘and getting the same answer: “You’re the sixth marimba call we’ve had today!”’

Both live performances occasionally vary the signature riff: the piano’s fourth note, low E, lies below the compass of the marimba, on which Gary had been obliged to substitute a B. The piano also handles the Shankar element. Mick’s solo – improvised in the studio on his Les Paul, as befitted an old song – has become a fixed element, played on the Strat he later favoured. At Passaic [B-04] the shapely flute-like solo emanates from Copping’s synth; at Leicester [C-04] he uses only Hammond. And whereas Gary needs to inform the American audience that this song has been a hit, the Brits recognise it and cheer unbidden. Pandora’s Box has remained a core concert-piece.

‘Gary didn’t like writing one song at a time,’ Keith Reid told me. ‘I had to send him a bunch of six or so lyrics to get him going: he likes dipping around.’ Brooker confirms this: ‘Half the time … I’ve written the tune already, and I look at [Keith’s] words thinking “I can make this one go with that”.’ Musically Fool’s Gold [A-02] is (in the press-kit’s curious words) ‘a pelvis puncher’, in diametrical contrast to its cerebral theme, ‘the loss of idealism’. Yet, far from undermining each other, these diverse ingredients combine to form a strident, angry classic.

Mick Grabham likes the song, and the aggressive ensemble approach it employed from the outset. He remembers ‘putting it together on the fly in the studio’. He knew Ramport from his session work, and found the new producers ‘great fun to work with … a different vibe, but not jarring. They were more concerned with the song and the way it went, much less involved in the recording technicalities.’

If the unconventionally-early guitar solo was a Leiber & Stoller ploy to vary Procol’s typical song layouts, it went unnoticed by 1 November’s NME, which began an article with the challenging ‘I don’t care how much Gary Brooker denies it, the last few P Harum albums have sounded particularly re-cycled because he and Reid have a tendency to structure all their songs the same way.’ Another novelty was the tight brass, punching those pelvises, and blowing more freely in the playout. These transAtlantic overdubs perhaps explain the long gap between the end of the Ramport sessions and the album’s August release.

The completed track is not built on the take heard on A-12 (witness its sour note at about 2m 34s, and subtle variations in piano and drum phrasing). Its sweet-toned Hammond, piano, and explosive drum entry recall an earlier Procol; the marvellous textural Strat-work, in verse two, is a welcome innovation.

Referring to Taking the Time [A-03] the press-kit commends its ‘clever wordplay about a man tired of lazing around.’ This somewhat undersells the lyric’s ruthless self-analysis (which, Reid told me, was inspired by Van Gogh, ‘living in the country’). Likewise ‘whimsical cocktail-lounge music meanders along’, from the same source, overlooks Brooker’s ingenious harmonic scheme. ‘I certainly hadn’t heard this one before,’ Grabham reports. Gary would sing new compositions at the piano, while his colleagues in the studio listened, and worked out their parts by ear; chord charts were seldom used. ‘Two diminished chords to start, brilliant!’ Mick says now. ‘But I can do without the horns: doesn’t sound like Procol Harum.’ Then he laughs: ‘This is all very well, nit-picking decades later.’

The

‘raw’ track [A-13] features a

free, bluesy piano prelude, and lets us hear

what Copping’s Hammond was doing until the horn

colouration came along (Chris in fact likes the usurpers’ ‘Ellingtonian

orchestration’ here). Yet Taking the Time was the only Procol’s

Ninth song missing from the band’s London Palladium showcase on 10

August 1975, at which they played a hefty 28 numbers, including two long

instrumental covers – The Blue Danube and Adagio di Albinoni –

that would later grace a rare, French single. The song has, rarely, been played

live since, ‘but it’s quite difficult,’ says Gary, ‘a lot of chords, not one you

can just knock out quickly.’ Any resurrected song must ‘work more-or-less first

time in rehearsal, which relies on Geoff [Dunn] having heard it before.’ Dunn

could, of course, study back-repertoire beforehand, but ‘I don’t encourage

that,’ says Gary, ‘because he might end up playing like BJ Wilson, and I would

prefer him to play as he felt it.’

The

‘raw’ track [A-13] features a

free, bluesy piano prelude, and lets us hear

what Copping’s Hammond was doing until the horn

colouration came along (Chris in fact likes the usurpers’ ‘Ellingtonian

orchestration’ here). Yet Taking the Time was the only Procol’s

Ninth song missing from the band’s London Palladium showcase on 10

August 1975, at which they played a hefty 28 numbers, including two long

instrumental covers – The Blue Danube and Adagio di Albinoni –

that would later grace a rare, French single. The song has, rarely, been played

live since, ‘but it’s quite difficult,’ says Gary, ‘a lot of chords, not one you

can just knock out quickly.’ Any resurrected song must ‘work more-or-less first

time in rehearsal, which relies on Geoff [Dunn] having heard it before.’ Dunn

could, of course, study back-repertoire beforehand, but ‘I don’t encourage

that,’ says Gary, ‘because he might end up playing like BJ Wilson, and I would

prefer him to play as he felt it.’

According to the press-kit this number’s ‘sparse [sic] arrangement heightens rapid-fire off-balance rhythms and Brooker’s gritty vocals’. This exciting track [A-04] includes the band’s first recorded use of Gary’s D6 Clavinet, which toured with him at this time (though apparently not to Passaic or Leicester). ‘For up-tempo music it beats rhythm guitar every time,’ he wrote in his ‘Keyboards’ chapter in George Martin’s Making Music (1983). It certainly blends well here with Grabham’s lead: ‘Gary played the riff, his little bit, and I played something that went across it.’ Mick recalls. ‘Not something that had to be worked on particularly.’

The ‘raw’ Unquiet Zone [A-15] has already seen some overdubbing, but Leiber & Stoller would subsequently splice in a different ending, clipping some 45 seconds, and add the brass at the expense of ‘Copping’s appearances astride his organ’ (NME’s wording). The track is already drum-dominated: ‘It was written with those rhythm stops, punctuated by a few chords at the end of each line,’ says Brooker now. ‘And BJ … well, he was never happy to sit there doing nothing, except in the build-up to some dramatic entry like in A Salty Dog. You can’t keep a good man down.’

So the song in concert effectively became a drum showcase, sometimes extending to twelve minutes (whereas Leiber & Stoller had halved its length, on starting to record it). At Passaic [B-05], where Copping reinforces the percussion with tambourine bashed against Hammond, it ends with eighty seconds of riffing guitar playout, quite a departure for Procol. The Leicester performance, which followed The Piper’s Tune, is omitted from this 3CD set: its recording was marred by a reel-change.

The new-found sharpness of the Procol’s Ninth sound springs not just from the new producers, but also from Mick Grabham’s change of instrument. In 1973, after a Cleveland OH show, Grabham and Cartwright visited the home of a backstage guitarmonger: there Mick found the 1957 Strat he still plays, and Alan his early Jazz Bass, both good investments. (Mick also recalls ‘the Veleno guy coming backstage in California, when he’d just started making his aluminium guitars. I wasn’t interested … bloody awful … but they’re worth a fortune now.’)

The Chrysalis press-kit finds this song ‘lyrically warlike’, adding ‘There’s enough ambiguity here to describe a last-ditch effort of any kind. But one that’s a lost cause.’ Procol and team sail close to mimetic fallacy, imitating this ‘lost cause’ element in a colourless, repetitive performance – then releasing it as the album’s second single (October 1975, c/w Taking the Time) to do battle with Queen’s latest (Bohemian Rhapsody!) and their own Homburg, tiresomely re-released by a previous record-company. Grabham, never ‘brilliantly excited’ by the song, now asserts that it was ‘a ridiculous choice for a single’: but Chrysalis – reversing their earlier mistrust of music journalism – were apparently swayed by the likes of Sounds, which numbered The Final Thrust among the album’s three ‘most resilient’ tracks, or the NME, whose correspondent called it ‘my own favourite’.

Brooker looks back on his ‘nice little tune, nice chords’, offering that he quite likes ‘the chorus answering, like a little army of some sort’ (Reid’s typescript bore a handwritten addition, ‘One for the troops’). But Gary concedes that ‘You’ve got to think short and sweet,’ setting such terse lines, ‘because there’s nowhere to go, lyrically speaking.’ The melody perhaps suggests a novelty item, like the cheerfully-bonkers Fresh Fruit from Exotic Birds; but the finished song feels somehow both facile and resentful. Brooker’s finger points to a cultural divide in the studio: ‘Leiber & Stoller, they’re Americans, and a lot of what Procol was capable of – and was usually doing – was not part of their repertoire.’ In his view, ‘Any quirkiness would not have been taken out, but it would not have been explored.’

Comparison of finished track [A-05] and raw performance [A-16] – ‘before Leiber & Stoller got at it’, in Grabham’s words – shows what the producers brought to this table. From Brooker they elicited a top-notch vocal performance, as everywhere on the album, and a nimble piano break; but their overdubbed second piano imparts a doggedly leaden feel, quite unlike the altogether dreamier, organ-led first sketch. Their ‘little army’ chorus supplants a melodic guitar figure. And they reinforce the already-insistent bassline with synchronised congas, recycling a gimmick used with The Drifters.

Thus the team struggled to find an ideal form for this song. New single or not, it featured in neither live set in this package; its rare onstage showings from 1976 suggest that, had it been road-tested before recording, it might have turned out more syncopated and less stagnant than the Ramport product. ‘Hey … nobody’s perfect!’ is Mick Grabham’s verdict.

It’s hard to tell whether various now-surprising press stories from the Procol’s Ninth era reflect journalistic error, or accurate reportage of Procol plans that subsequently changed. Record Mirror, a month before the album’s 1 August release, intimated that I Keep Forgetting [A-06] would be released as a single on 18 July: it wasn’t, of course. The song, by Leiber & Stoller, was Procol’s first-ever non-original on a studio album (1970’s pseudonymous ‘Liquorice John’ project still languished in the vaults) and it rather shocked hard-core fans for whom, perhaps, its writers were not pop deities: their mention at Leicester elicits no audible crowd reaction.

Brooker recalls how, each morning at Ramport, Procol ‘played at least one Leiber/Stoller song, showing off our knowledge, trying to impress them.’ Mike Stoller, ‘the music half of the team’, particularly enjoyed these off-the-cuff covers of Elvis, Ben E King and so on. Thus encouraged – and claiming, ‘This will suit you guys!’ – Jerry and Mike proffered many newly-written originals for the Procol record. One such was Tango (eventually recorded, in November 1975, for Peggy Lee’s Mirrors album). In Mick’s words ‘it sounded like they’d tried to write a Procol Harum song.’ Like the hit-buying public, Leiber & Stoller evidently cherished Procol’s ‘mythological’ style, and Tango heaves with ersatz echoes of an earlier Reid: ‘… a gray merchant ship turns black in the sun … one-eyed Etruscans play follow-the-leader’. ‘But it’s like the way Steptoe and Son didn’t translate to American TV,’ is Grabham’s analysis. ‘They’re just missing the point.’

Gary

relates how ‘We turned down every single one of

[their new offerings] … but we did in the end settle on I Keep Forgetting

[A-06]. He’d been hugely impressed, at the Ready Steady Go! TV studios,

when Chuck Jackson had performed his 1962 hit version; the Procol’s Ninth

arrangement is very different to Jackson’s, yet still soulful, and it swings …

and it’s a favourite of Chris Copping’s.

Gary

relates how ‘We turned down every single one of

[their new offerings] … but we did in the end settle on I Keep Forgetting

[A-06]. He’d been hugely impressed, at the Ready Steady Go! TV studios,

when Chuck Jackson had performed his 1962 hit version; the Procol’s Ninth

arrangement is very different to Jackson’s, yet still soulful, and it swings …

and it’s a favourite of Chris Copping’s.

Both Procol’s live performances here glisten with juicy organ, guitar and piano, an ample alternative to the record’s brass additions. At Passaic [B-09] Mick’s Les Paul solo copies his guitar line devised, at Ramport, on a 1962 Fender Esquire. But Brooker’s namechecks for the songwriters (echoed as ‘Leiber & Stroller’!) herald some downbeat comments on the album’s progress. ‘I haven’t seen it in the charts yet,’ he says. ‘Still hoping for good things. Otherwise we’ll have to make another one.’ (Next on that night’s bill, the pre-megastardom Fleetwood Mac – whose eponymous album slightly predated Procol’s Ninth – doubtless shared Gary’s wish for ‘good things’ … and, in their case, hope was spectacularly realised). At Leicester [C-09] Gary’s Leiber/Stoller references feel less than reverent: by then it was clear that the album – which he calls ‘a sleeper’, omitting even to state its name – was not the much-anticipated commercial success.

The single that fans had been expecting was Without a Doubt. Introducing it as The Poet, way back in October 1974, Brooker had told a Bradford audience to expect it ‘in stores and jukeboxes soon’. The band went into Phillips Studio near Marble Arch (where Grabham had recorded two albums with his former band Cochise, and his Mick the Lad solo album) and recorded, with engineer Roger Wake, ‘a very good demo’, in Gary’s words. ‘We always thought that song was catchy, for Procol anyway,’ he adds. (With hindsight, its churchy chorus redoles more strongly of Exotic Birds than of Procol’s Ninth: some fans suppose The Poet changed names when it was no longer a companion-piece to The Idol.)

The two extant Poet demos are identical but for BJ’s 3¼-second solo drum-breaks preceding each of the three choruses. What we might call ‘Version A’ features three very different breaks, all syncopated to the point of eccentricity (arguably epitomising a rare reproach for Wilson’s work, which his one-time Procol colleague Matthew Fisher voiced to Daily Express journalist Paul Carter in 1997: ‘BJ started to get a bit fancy, pompous, like he felt he had to do something strange and that no other drummer would do.’). But in ‘Version B’ BJ’s final drum-break from ‘A’ is used three times, copied and dropped into two earlier gaps. We cannot ascertain which version Procol Harum played to Bob Ezrin in early 1975, when disco was the upcoming trend: but the Canadian – perhaps responding to the lengthy gaps between verse and chorus – did not sense much dance potential. ‘He showed us a dollar sign on a gold chain around his neck,’ Gary remembers. ‘“This is where I’m at, fellas!” he said.’

Track A-14, discovered among the Ramport relics, is without a doubt the Phillips demo of The Poet, a ‘Version C’, with two of BJ’s madcap drum-breaks now excised; just the third – perhaps the most straightforward – is retained. Liking this demo’s vocal sound, Gary played it to Leiber & Stoller. ‘Of course, if you do that, they immediately have to do something different,’ he laughs now. ‘Otherwise, why are they there?’

The album version [A-07] rather flattens the detailed emotional contours of the demo. The lavish, hard-edged brass arrangement feels ill-suited to the domestic scene (‘I’m going downstairs’ etc) where the would-be ‘serious’ writer declares his shifting ambition each day. The echoey passages featuring tambourine and rising left-hand piano are sonically interesting, but undermine the cocky feel, in the demo, that portrays the vanity of ‘the critics will love it’ etc. The producers tamed BJ’s risky drum-breaks, halving their length; yet they chose to double the commonplace instrumental passages preceding each verse.

Gary feels the final version ‘wasn’t quite as groovy as our demo.’ ‘Groovy’ may be a surprising Procol epithet, but it tallies with ‘a frolicky tune’ from the press-kit, which astutely continues, ‘It becomes more impassioned as self-doubt racks the poet. Kept good-humoured, though, by the poet’s delusions of grandeur.’ But is this good humour really evident on the album?

Procol Harum attack The Piper’s Tune at Leicester [C-05] with crazy relish, from the rough Glaswegian count-off to the impromptu thirty-second reprise, with its super-dotted piano-rhythm and busy snare-drum. Brooker’s dramatic vocal, despite the high tessitura, aptly serves Reid’s disturbing, vengeful lyric (a cousin of Simple Sister). The guitar makes a spooky entry before verse two, and verse three’s piano delivers some emphatic ‘collapsing triads’, a Brooker signature.

It’s worlds away from the performance [A-08] on the record, which elicits the word ‘dirge’ from both Copping and Grabham, in independent conversations. As the Pandora B-side, it made a low-wattage advert for the album. Leiber & Stoller’s production oozes ennui, falling short of the press-kit’s promise of ‘a veritable Olympian refrain’, and underselling the composer’s harmonic inventiveness. This song shares, with Without a Doubt and Grand Hotel among others, a neat Brooker trick: the tune’s gradually-shifting tonal centre (assisted here by a brief transitional progression recalling Hey Jude) makes each successive verse appear to start in a higher, fresher key (cf the ‘Shepard Scale’ auditory illusion).

Brooker construed Reid’s lyric (an outright contradiction of its parent proverb, ‘he who pays the piper calls the tune’) in Scottish terms. ‘I’ve always liked the sound of bagpipes,’ says Gary now, ‘and although they’re not on it, the motifs are.’ In March Sounds had trailed ‘Piper’s Dream [sic] with organist Chris Copping making the piping sounds’: Chris remembers using a Lowrey organ’s ‘semitone bend pedal for droning’, and Grabham recalls ‘the only time I’ve ever used the Strat’s whammy bar, to get that bagpipey drone’.

Yet apart from those bagpipe imitations, Gary’s intermittent cod-Scottish accent is the only Caledonian element on the track. ‘Perhaps Americans don’t quite understand the atmosphere of a piper standing on the edge of Edinburgh Castle,’ he explains. ‘Leiber & Stoller, as producers, didn’t realise the song as it could have been realised.’ Disdaining additional instrumentation or textural variety, they edited Track A17 by twenty seconds (thereby losing a suspect note), recorded Brooker’s improved vocal, and left it at that.

By contrast, they heaped care and imagination on Typewriter Torment, which rivals Pandora’s Box in terms of production detail. Perhaps Leiber & Stoller were fired by the enthusiasm Procol brought to the raw track [A-18], a tight, energetic performance of ingenious inventiveness. In the chorus, for instance, Grabham has adapted a zigzag motif from Andy Williams’s 1963 hit Can’t Get Used to Losing You, contributing melodic and rhythmic detail such as The Piper largely lacks.

The

elaborate, well-integrated production [A-09] refines the vocal line, ditches the

neat ending and the hollered ‘typewriter!’ (with its shades of Paperback

Writer), and adds hand-claps, oohs and aahs, drum-phasing, and final-verse

congas. Copping’s melodic skill, undervalued elsewhere, is foregrounded at last:

‘I thought my organ solo was OK,’ he told me. And, though there’s little

guitar-solo action in the Ninth’s final few tracks, Grabham

overdubs an effective ‘kind of doinky’ sound, played on an ‘Electric Sitar’

guitar – its dozen or so sympathetic strings activated by vibrations in the

normal six – manufactured by Coral/Danelectro and popularised by the Stones’

Paint it Black. ‘Typewriter was quite complex in its make-up,’ Gary

confirms now, ‘and it came out well, one of the highlights.’

The

elaborate, well-integrated production [A-09] refines the vocal line, ditches the

neat ending and the hollered ‘typewriter!’ (with its shades of Paperback

Writer), and adds hand-claps, oohs and aahs, drum-phasing, and final-verse

congas. Copping’s melodic skill, undervalued elsewhere, is foregrounded at last:

‘I thought my organ solo was OK,’ he told me. And, though there’s little

guitar-solo action in the Ninth’s final few tracks, Grabham

overdubs an effective ‘kind of doinky’ sound, played on an ‘Electric Sitar’

guitar – its dozen or so sympathetic strings activated by vibrations in the

normal six – manufactured by Coral/Danelectro and popularised by the Stones’

Paint it Black. ‘Typewriter was quite complex in its make-up,’ Gary

confirms now, ‘and it came out well, one of the highlights.’

The press-kit highlights a contrast between music and words: ‘Steamrolling guitar and Brooker’s honky-tonk piano provide a raucous backdrop for this tongue-in-cheek lament about Reid’s habit.’ It considers the ‘lament’ to be ‘autobiographical’ (as did Sounds on 29 March, in an early mention of the song); Keith later felt too many critics had assumed he was suffering from writer’s block which, he told me, had afflicted him only in the run-up to 1970’s Home album. Too few, evidently, had believed the press-kit’s ‘tongue-in-cheek’, or its clarification of his habit: ‘an addiction whereby the author can’t stop writing’ (my italics).

But Reid’s writing did stop there as far as Procol’s Ninth was concerned. Eight Days a Week [A-10], another song by legendary songwriters from outside the band, provided a perplexing anti-climax to this puzzling album … as well as emboldening the ‘writer’s block’ theorists. Two cover versions? Sounds, in late March, had indicated that ‘prospective tunes … seem to be in abundance … there could be an extended piece in the tradition of In Held ’Twas in I.’ As aforesaid, this could be misreportage; but it could equally be an unexpected early warning of The Worm and the Tree from the band’s next album. And Gary’s compendium of typed Reid lyrics includes various titles – Man Overboard, Time-Bomb Baby – that haven’t been heard on stage, or anthologised in Keith’s My Own Choice (Charnel House, 2000). Chris Copping feels that So Far Behind, another Pandora’s Box co-eval, would have provided a meatier finale.

‘We had tried that one over the years from time to time,’ Gary declares (it was in repertoire by January 1976, but not recorded until 2003’s The Well’s on Fire). Understandably, in September 2018, he no longer recalls what other Brooker/Reid numbers might have been in contention for ‘Procol’s IX’, as he likes to write it. In September 1975, however, Procol Harum visited the Netherlands for TV and radio promotion; listening to KRO’s Theo Stokkink Show on the radio, Procol scholar Frans Steensma transcribed Gary’s fresh recollection: ‘It ended up, when we nearly finished [the album] that we had a slot there that needed a certain sort of song. The ones we had prepared didn’t fit into that. We had a comedy song and a very slow classical-type piece; those were the two main choices. The atmosphere of the album by then had a much more earthy feel to it … and this is where we put in I Keep Forgetting and Eight Days a Week.’

While it’s intriguing to speculate over ‘the comedy song’ and the ‘classical-type piece’, it’s also anyone’s guess – if a Beatle cover was needed for reasons of balance – why Eight Days a Week (never a UK hit, though successful in America) was chosen. ‘It’s a very good song … one of the Beatles’ songs that isn’t particularly regarded as a great song,’ Gary told Stokkink. ‘We used to play it as an encore,’ he told me recently, ‘because it would have been unexpected, and we like the unexpected. It was probably Mick Grabham’s idea.’

Mick’s recollection differs: ‘Why we even did it is beyond me,’ he laughs. ‘For God’s sake … Happiness is a Warm Gun would have been more à propos.’ (He’d played that live, and recorded Strawberry Fields Forever, with his early band, Plastic Penny). ‘I would never have suggested putting Eight Days on the album: but I didn’t object at the time, so … what can I say?’ Listening to it lately, for the first time in twenty years, Gary decides it’s not a bad version. ‘We’re not trying to make it into a Procol song … we play it quite like the Beatles.’

The standout feature of the Beatle original is the vocal camaraderie of Lennon and McCartney’s harmonies, John’s exuberance in particular. Procol’s version is a fourth lower, and somewhat slower; and though Gary’s vocal adds melodic interest to Lennon’s characteristically horizontal tune, vocal harmonies are absent. The Beatles’ cheery clapping is adapted into a different and more unvarying rhythm. It’s ‘a carousing celebration’ according to the ever-inventive Chrysalis press-kit, which then comes close to damning the track with faint (and dubious) praise: ‘Better hand-clapping here than in that famous original.’!

LEGACY LIVE

Amid rehearsals for the Ninth, Procol had continued to play live. Their prestigious Rainbow Theatre gig was preceded by warm-ups in three UK university cities, beginning in Bristol. Album work was finished by April, and in June and early July they played thrice more at home, then seven times in Scandinavia, where their large, loyal following persists to this day. Another month off, and promotional duties started in earnest: Top of the Pops in early August; then a pair of UK gigs, the second being the London Palladium; then a French festival, and a short Mexican trip (three shows) at the month’s end.

After two further TV recordings in September, Procol undertook about a score of North American shows, of which Passaic (Disc B here, recorded Friday 17 October) was the eighth. Passaic is a densely-populated, smallish city in New Jersey, which spawned such musicians as Fats Waller, The Shirelles, and Donald Fagen. To its Capitol Theatre came a Procol line-up, established in September 1972, that collectively embodied 29 years of Harumcraft (Brooker and Wilson eight years apiece, Copping six, Cartwright four and Grabham three). Their average age was almost 29½, Gary, Chris and Alan having turned thirty since completing Procol’s Ninth. Surviving film – of patchy technical quality – suggests an ideal matching of energy and experience in the band, and contemporary accounts indicate that the night’s headliner, Fleetwood Mac, sounded disappointing by comparison.

Following the US shows, Procol played thirteen more during a Scandinavian fortnight, six on a nine-day UK tour, and finally, in December, five Northern European concerts. The present Disc C was recorded, by Radio Trent, at the second of those British gigs. Leicester is a large city in the UK’s East Midlands, cradle of such musicians as Jon Lord, Tony Kaye and Engelbert Humperdinck. Its highly-regarded university is alma mater to Chris Copping BSc, who left The Paramounts to study there from 1963 to ’66. The Procol’s Ninth tour programme fancifully claims he then embarked on a ‘post-graduate thesis on The Relative Specific Gravity of British Beers’ – a Chris Briggs joke. As well as working to support wife and child, Copping was in fact studying for a PhD in organic chemistry, but all this was ‘interrupted when Mr Trower phoned me in 1969’ and he joined Procol Harum, as both bassist and organist. By Saturday 29 November, on the very stage in the university’s Queens Hall where he’d seen Brian Jones leading the Stones (‘they cost £500 and it was five bob to get in’), he had settled wholly on Hammond, which is mixed good and loud on the broadcast’s surviving tracks.

******

Procol’s most famous song is rapturously received in the Queens Hall [C-13], and the band plays one of two verses omitted, in 1967, to fashion a viable single. In younger years Keith Reid had neither read nor written poetry: ‘I really don’t remember learning anything at school,’ he told me. His early criterion for a Procol lyric was simple: ‘It’s got to sing well. It can look dumb on paper, but still sound great.’ Chris Copping starts and finishes AWSoP with the classic organ line, but elsewhere his baroque variations ensure variety in a long performance. His pibroch-like improvisational talent could have enriched The Piper’s Tune, under different producers.

Conquistador

opened Procol’s début, self-titled album in

1967; the band disliked the ‘scrunched-up’ sound of that version, but valued the

song: in an overhauled arrangement, recorded live with the Edmonton Symphony

Orchestra, it became their third major chart hit. This collection’s two live

versions follow the ‘Edmonton’ template closely, though with less urgency.

Leicester [C-03] features an exciting organ break, Passaic [B-03] a strong

guitar solo, exploring the range of Grabham’s Strat. This early in the show, the

Capitol Theatre sound-balance still needs tweaking: ‘There’s too much now,

Brown,’ Brooker observes. ‘Put it down a little bit, please.’ Is he addressing

Procol roadie Denny Brown, the spoons-player from 1973’s A Souvenir of

London? ‘Brown was a popular name for anyone,’ Gary asserts now. ‘I might

say “What you doing, Brown?” to Mick Grabham, or Franky Brown, my wife.’ His

explanation is characteristically opaque: ‘It comes from somewhere down the

King’s Road, where you could buy half a pair of brown trousers.’

Conquistador

opened Procol’s début, self-titled album in

1967; the band disliked the ‘scrunched-up’ sound of that version, but valued the

song: in an overhauled arrangement, recorded live with the Edmonton Symphony

Orchestra, it became their third major chart hit. This collection’s two live

versions follow the ‘Edmonton’ template closely, though with less urgency.

Leicester [C-03] features an exciting organ break, Passaic [B-03] a strong

guitar solo, exploring the range of Grabham’s Strat. This early in the show, the

Capitol Theatre sound-balance still needs tweaking: ‘There’s too much now,

Brown,’ Brooker observes. ‘Put it down a little bit, please.’ Is he addressing

Procol roadie Denny Brown, the spoons-player from 1973’s A Souvenir of

London? ‘Brown was a popular name for anyone,’ Gary asserts now. ‘I might

say “What you doing, Brown?” to Mick Grabham, or Franky Brown, my wife.’ His

explanation is characteristically opaque: ‘It comes from somewhere down the

King’s Road, where you could buy half a pair of brown trousers.’

Like Pandora’s Box, Conquistador was coeval with A Whiter Shade of Pale and Homburg: four UK hit singles, written within two or three months, but charting over eight years. ‘Well there you are,’ says Gary now. ‘A bit of talent in the early months, then work after that! When you start writing, you get these floods of ideas, but after a while … it’s still floods of ideas, but you’ve got a reputation, and a style, that come into the process too.’ As stated above, the chart-oriented public likes their Procol fanciful: no single of the band’s in Reid’s mature, pared-down style has sold in comparable quantities.

The enduringly popular Cerdes [B-08] was Procol Harum’s longest, bluesiest track, and arguably bore the strongest traces of Reid’s early Dylan influence: it’s intriguing how Brooker invests such inscrutable imagery with such passion. Cartwright’s bass ushers in the super-long introduction, and BJ contributes some counter-intuitive cross-rhythms. As Grabham’s fine Les Paul solo winds down, it dovetails unexpectedly with Brooker’s piano lines. The original faded out; at Passaic the song gets an unpredictable ‘firm’ ending.

This is the influential title-track from Procol Harum’s 1968 album; live in ’75 the song grows a closing guitar solo, and Copping’s organ copies Matthew Fisher’s inspired playing only in the verses, not in the featured solo. The elegantly-crafted bassline is memorable, the words vividly pictorial: it would surely have been a hit if released as a single.

At Passaic [B-01] it followed Bringing Home the Bacon, of which only part survives. Counted off in French, it suffers a false start, and the organ is mixed rather low; but it’s boldly audible at Leicester [C-01], as is Gary Brooker’s unfortunate cold. Compare the capricious drum fills, in each performance: they epitomise the flair of BJ Wilson, for whom each performance was a new invention.

A Salty Dog is the marvellous title-track from Procol’s third album (1969); composed in Switzerland, the music ‘took five minutes’ according to Gary Brooker. Originally recorded at Abbey Road Studio 2, it was ‘probably our first time on eight-track’. Both these live versions extend the second instrumental, concluding a tone higher ‘to make it more difficult for me to sing’ as Gary claims at Passaic [B-06]. He explains that the song is a Wilson favourite: BJ makes an unmistakable mark with his first, complex entry. Tempi rise and fall like waves, but Grabham shrugs this off: ‘If it sounds good, I don’t give a shit,’ he told me.

At Leicester [C-08] BJ is again name-checked before this number (since his death in 1990, performances have frequently been dedicated to him). His expansive 45-second cymbal prelude evokes a seascape more subtly than the piratical exclamations in the background. Grabham’s melodic guitar in the second instrumental is notable; likewise the way Brooker’s vocal triumphs over congestion.

This mighty piece is the jewel in the dark crown of 1970’s masterpiece, Home. Writing together, Brooker and Reid planned a song that defied pop-music’s reliance on repetition. At Leicester [C-02], following an extended Copping prelude (with irreverent sea-shanty interpolations), the mood shifts from verse to varied verse; yet the song’s dramatic core capitalises on pure repetition, an uneasy rising scale heard, at various pitches, some 23 times, the last dozen topped by Grabham’s ferocious guitar-storm.

Simple Sister opened 1971’s Broken Barricades album. Reid tells me ‘whooping cough’ is intended literally: this isn’t an STD song! ‘Keith’s work is very quick, not a thought-out clever thing,’ Brooker remarks. The song [B-12] closes the Passaic show (US audiences enjoy a guitar showcase, but the riff was actually written on piano). Grabham’s huge string-bend in the intro is a daring innovation; otherwise many Trower lines are respected as compositional elements. Terrific guitar work ushers in an eccentric bass solo, in the ‘Cool Jerk’ section, from ‘Alan Sharkwright’ (Gary’s tee-shirt sports the iconic Roger Kastel poster for Jaws, released that June).

This fiery number also comes from Barricades. Its words (written in New York) feel more substantial than the music; as Brooker admits, ‘It’s really just a drum solo’. At Passaic [B-11] nearly sixty percent of the performance is unadulterated ‘Blowjob Wilson’ (Mick’s tongue-in-cheek appellation): and his solo, unlike its rather stilted album equivalent, invites repeated listening. It doesn’t merely testify to BJ’s mastery of rudiments, but rather draws us in, through dynamic and tonal variety, to eavesdrop on an intimate musical conversation among the various elements of his kit. Choosing to remain onstage, Brooker grunts and whoops approval. Power Failure likewise preceded the encores at Leicester, but is omitted from this 3CD: another recording marred by a reel-change.

Rock

music is typically in 4/4 time, but Brooker favoured 3/4 occasionally, for

poignant effects (Magdalene, Too Much Between Us, Nothing that

I Didn’t Know, Broken Barricades, A Rum Tale). The waltzing refrains

in 1973’s Grand Hotel, from the eponymous album, share that nostalgic

feel, but the nearby ascending accelerando, also in triple time, has a

rowdier flavour. Perhaps it was Procol’s mastery of both moods that prompted

‘The City Fathers of Vienna’ to commission their Blue Danube for a

light-hearted album commemorating the

sesquicentennial of Austria’s ‘King of Waltzes’ … see Track C-10

below.

Rock

music is typically in 4/4 time, but Brooker favoured 3/4 occasionally, for

poignant effects (Magdalene, Too Much Between Us, Nothing that

I Didn’t Know, Broken Barricades, A Rum Tale). The waltzing refrains

in 1973’s Grand Hotel, from the eponymous album, share that nostalgic

feel, but the nearby ascending accelerando, also in triple time, has a

rowdier flavour. Perhaps it was Procol’s mastery of both moods that prompted

‘The City Fathers of Vienna’ to commission their Blue Danube for a

light-hearted album commemorating the

sesquicentennial of Austria’s ‘King of Waltzes’ … see Track C-10

below.

Brooker’s Strauss arrangement, bizarrely slotted into Grand Hotel at Passaic [B-10], got the crowd out of their seats. One delighted earwitness wrote to ‘Beyond the Pale’ (the compendious Procol archive at www.procolharum.com) that ‘after perhaps a good three minutes or more [Procol] fell back into the finale of Grand Hotel’. In fact the Strauss lasted 8½ minutes, an ostrich-sized cuckoo dwarfing the Procol classic it nested inside.

Such musical stowaways were common at this era, as if Procol were an orchestra playing requests in the sumptuous hotel Reid’s lyric envisaged. At the Rainbow Theatre’s farewell show, on 16 March, Procol had sandwiched in Over the Rainbow; likewise they’d inserted the TV theme from Sunday Night at the London Palladium during their mammoth showcase there on 10 August. On many occasions, including Leicester [C-06], Brooker sang a tango tribute to Humphrey Bogart; surprisingly, neither he nor Copping now recalls this well-attested comic phenomenon.

The words of this Grand Hotel novelty were inspired by street musicians, as Gary explains before the Passaic performance [B-07], though probably not by celebrity busker Don Partridge himself. Brooker sings out front, but the ‘extraordinary paraphernalia’ he mentions is a six-string resonator guitar, not the full one-man band rig. Cartwright’s ‘Don Brooker on cash-register’ comment alludes to Partridge’s improbable late-Sixties’ chart successes.

Keith Reid had ‘not expected [Souvenir] to sound like a busking song’, but here it does, thanks in part to Copping’s laboriously-fettled five-string banjo. The spoons and barrel organ from the record are missing, but we get more drums and plenty more swagger: it’s very well received.

Beyond the Pale [C-07] is a crowd favourite from 1974’s Exotic Birds and Fruit; producer Chris Thomas’s studio wizardry realised a convincing Eastern bloc sound-world appropriate to the title and questing lyric … one wonders what wonders he might have wrought with The Piper’s Tune.

Procol have two banjo stage-numbers, but sadly no banjo-tech to pre-tune the instrument in the wings. Despite Copping’s comment, his mic was most definitely on: one would not wish the banjo any louder! In the Procol’s Ninth tour programme (by self-styled ‘rich man’s lackey’, Chris Briggs) Copping is dubbed ‘the world’s worst banjo-player’, yet he creditably negotiates the song’s labyrinthine ‘Norwegians’ (Procol’s Cockney rhyming-slang for ‘chords’ – think ‘fjords’). ‘A very funny man,’ says the banjoist now. ‘Briggsy could have done stand-up about [Chrysalis moguls] the butterfly boys.’

As Strong as Samson [B-02] originated on Exotic Birds, and tardily came out as a single (early 1976, b/w The Unquiet Zone) after The Final Thrust flopped. It was written (‘from top to bottom’) after Keith Reid heard a Watergate-era radio documentary likening Washington to ancient Rome which, at the time it fell, was ‘full of lawyers’. ‘That’s a hard chorus to sing,’ Gary Brooker told me, ‘but at that point in my life I was yodelling quite a lot.’ Live at Passaic [B-02] each performer contributes detailed, subtle drama; such felicities feel sparse on Procol’s Ninth.

This Johann Strauss II favourite presented a steep learning curve for the Procols; on accepting the commission (see Track B-10 above) they discovered it was a complex work, with numerous interrelated sub-themes. Gathering at Apple in Savile Row, before ever playing it live, they spent a day recording the piece in sections, supervised by Chris Thomas. ‘By pure fluke,’ Grabham now recalls, the various pieces were perfect tempo-matches. All the Beatles’ gear – ‘the guitar cases, the drum kits, the Vox amps’ lay piled in a glass-walled booth adjoining the studio. ‘Nowadays you’d take a million photographs,’ says Mick, ‘but at the time you just walked past.’

The Blue Danube dates from 1866, when its composer was 41, yet Procol’s electrification was well-received (according to 1975’s In Strauss und Bogen album sleeve, it made them almost Ehrenösterreichern – ‘honorary Austrians’). Copping didn’t much like Strauss, ‘the AM radio of Vienna,’ in his view, ‘but at least he gave Mick a chance to show how orchestral he could be with a volume pedal.’ ‘Not our bag,’ Gary Brooker advises the Leicester audience [C-10], ‘but we’ll give it a try’. The band’s Danube avoids AM radio cheesiness: it’s played with conviction and style, but not without mistakes, some playful, as at about 6½ minutes, when Chris Copping and Gary Pahene (as he namechecks himself at the end) swap intentional wrong notes. ‘Real class,’ whispers Grabham. His Les Paul tone is beautiful and at times breathy; in 1976, choosing a B-side for their all-instrumental Adagio di Albinoni single, Procol preferred the feel of a live concert take (Bournemouth, 17 March 1976) to the Austrian version, recorded with the Strat.

There are no Procol studio recordings of the last two non-originals played at Leicester. The band’s next dip into music history is Be Bop-a-Lula [C-11] which, dating from 1956, predates most students in the audience (they might have known Lennon’s cover, or McCartney’s; it was a Hamburg-era Beatle staple). The rabble-rousing call-and-response session (the rabble providing its own echo) now betrays scant trace of Brooker’s cold; his voice and Grabham’s blend sweetly as they tackle Gene Vincent’s début hit which itself, paradoxically, used no harmonies. If Leiber & Stoller had coaxed such singing from Gary and Mick for their Eight Days cover, it might have turned out more distinctive.

Eight

Days is not a scheduled encore, however; instead Procol revert to a

Paramounts’ standard, published in 1853 and written by Stephen Foster

(1826–1864). Old Black Joe was originally a parlour ballad (Paul Robeson

sang it as a plantation spiritual), but the Paramounts’ version derives from

1960’s spirited Jerry Lee Lewis revision. Whereas Robeson coyly sidesteps the

word ‘black’, Gary [C-12] induces his audience to sing it … in German! Old

Black Joe features on the Paramounts’ 2005 reunion DVD I’m Coming Home,

and is a well-loved Brooker standby. Curiously, as in Procol’s Seem to

Have the Blues (Most All of the Time) and Dead Man’s Dream, its

narrator has already embarked on the afterlife.

Eight

Days is not a scheduled encore, however; instead Procol revert to a

Paramounts’ standard, published in 1853 and written by Stephen Foster

(1826–1864). Old Black Joe was originally a parlour ballad (Paul Robeson

sang it as a plantation spiritual), but the Paramounts’ version derives from

1960’s spirited Jerry Lee Lewis revision. Whereas Robeson coyly sidesteps the

word ‘black’, Gary [C-12] induces his audience to sing it … in German! Old

Black Joe features on the Paramounts’ 2005 reunion DVD I’m Coming Home,

and is a well-loved Brooker standby. Curiously, as in Procol’s Seem to

Have the Blues (Most All of the Time) and Dead Man’s Dream, its

narrator has already embarked on the afterlife.

******

BEYOND THE NINTH

Life after Procol’s Ninth involved a personnel shift: Alan Cartwright left the music business, Chris Copping took his place on bass, and Peter Solley came in on organ and synths. But fan-theories of a ‘three-album line-up lifespan’ don’t ring true with Gary Brooker: ‘It’s just coincidence. I like working with people I know; we’re friends, very sociable when we’re playing, recording or on the road. Maybe with Alan it had just run its course? Chris always played great organ, it was just “Time for a change”. He plays great bass as well.’

Procol Harum didn’t record with Leiber & Stoller again: ‘I’m not sure it was a hundred-percent successful teaming,’ Brooker told me, ‘but there was no bad feeling; they’d been the right choice at the time.’ Both he and Grabham reject, in colourful terms, the claim in a 2012 book that Procol had to extricate themselves from a contract with the Americans. ‘I don’t think we’d ever envisioned that Procol’s Ninth would be the start of a long relationship,’ says Gary; and in Mick’s view ‘They dropped us for Elkie Brooks: they could use their own songs there, and they got another hit out of it.’ Brooks’s Two Days Away album, recorded in 1976, yielded the chart single Pearl’s a Singer, co-written by Jerry and Mike. ‘You accepted that they were interested in hits,’ Mick told me. ‘They were songwriters.’

This Esoteric 3CD collection demonstrates how, despite producing a worthy hit single, Leiber & Stoller presided over a period of diminished risk-taking and diluted eccentricity for Procol Harum in the studio, and also how these endearing qualities (later re-established, in monstrous abundance, on side two of 1976’s Something Magic) burnt brightly as ever while the touring band out-performed rivals, and entranced audiences, throughout the world.

The record Procol made with Leiber & Stoller was released in Argentina, Australia, Austria, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, Japan, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Scandinavia, Spain, the UK, Uruguay, the USA, Venezuela and Yugoslavia. ‘No other album by Procol Harum was released on such a worldwide scale,’ according to Frans Steensma. Chris Copping remembers a quip from press-man Briggs about ‘Procol’s knack of touring Outer Transylvania when they were needed to promote a new album’, namely 1974’s neglected classic Exotic Birds and Fruit. One could perhaps argue that Procol’s Ninth received the marketing that Exotic Birds had more richly deserved; and it’s intriguing to ponder how Procol’s progress might have prospered, had Chrysalis played their promotional cards in a different order.

© Roland Clare,

Bristol UK, September 2018

Many thanks to Gary Brooker MBE, Chris Copping, and Mick Grabham, who gave fresh

interviews for this essay; to Keith Reid for less recent assistance; to helpful

informants Peter Christian, Jacob Cunningham and Mick Mangan; and particularly

to Frans Steensma, for generous sharing of research.

| More liner notes from the same author | About this remastered CD | |

|

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |