Liner note by Roland from

BtP • February 2019

BAND OF CHANGES

‘The only thing that I really know about them is that Whiter Shade of Pale …

.’ Thus began a memorably preposterous assessment of Procol Harum, published

by Rolling Stone in 1969, in which the interviewee, Robbie Robertson from

The Band, went on to say that he’d ‘… heard vaguely a few records by them, and

they’re still singing that same song. I don’t know why they want to do that.’

Well of course they didn’t do that: Procol’s evolution from record to

record was striking, and 2017’s Novum album still bears

witness to the progressive spirit in which Gary Brooker and Keith Reid founded

the band fifty years before, displaying a sustained reluctance to cover the same

ground twice. Arguably that epithet ‘progressive’ (not to be confused with its

tiresome offshoot, ‘Prog’) guarantees that every Procol Harum album can be

classified in some way as ‘transitional’: but this Esoteric re-issue comprises a

triptych portrait of the group in 1971, the year of their most conspicuous

changes of all.

CD A presents Procol’s fifth

studio album, Broken Barricades, first released in May 1971, with

a ‘bonus’ version of every track. CD B features a live US radio

broadcast, predating the album’s release and featuring its four musicians

(Gary Brooker, voice and piano; Chris Copping, bass and organ; Robin Trower,

guitar, bass and vocal; and BJ Wilson, drums and percussion) followed by a

four-song BBC studio spot recorded a half-year later by the five-piece Procol

(Brooker and Wilson, with Chris Copping on organ only, and ‘new boys’ Dave Ball

on guitar and Alan Cartwright on bass). CD C, recorded just nine days

later, contains a Swedish radio concert given on 16 October.

This brief essay starts with

some background, considers the Barricades tracks and their

variants, then surveys the ‘legacy tracks’, from earlier records, aggregated in

chronological order of their release.

RECORDING

An NME interview from 5 June 1971 – much relied-upon by subsequent

commentators – mistakenly says that recording started in February 1971; in fact

an extant tape-box (see illustration opposite) lists three Barricades

songs on a master-reel (oddly, ‘#2 of 1’) dated 29 December 1970, suggesting

work had begun within weeks of Procol’s return from North America on 26

November. Furthermore the studio diary of tape-operator Chris Michie (archived

at ‘Beyond the Pale’, www.procolharum.com) logs some sixteen sessions – starting

at 2pm and often running into the small hours – during January.

The band used

Associated Independent Recording, opened 6 October 1970 by George Martin and

associates, on the fourth floor of 214 Oxford Street in

London. AIR was ‘a top studio at the time,’ Robin

Trower told me, ‘in fact, the studio.’ Procol usually had ‘a big

struggle to sound good on record,’ as Keith Reid puts it now; but AIR’s sound

left them ‘knocked out’. As well as Michie, ‘a lovely bloke’ according to Keith,

the team included John Punter, ‘a great engineer, a very “up” person’, and of

course producer Chris Thomas (‘much more laid-back’).

‘We actually found Chris in

a back room in George Martin’s offices,’ Gary Brooker told me. ‘We’d been

talking to George because we needed a producer once recording Home

with Matthew Fisher fell apart.’ Thomas had played on the Beatles’ ‘White

Album’ and ‘had produced just one record, for the Climax Blues Band

[1968]: but I’d liked him. By Broken Barricades he’d really proved

himself.’

‘We recorded the rhythm

tracks live, and did overdubs as required,’ says Gary now. Barricades

‘took longer than Home,’ Thomas told Canadian journo Ritchie Yorke,

‘but a lot of time was spent fooling around.’ About this, more below …

PRESENTATION

The new album was given a promising title, unlike 1970’s ignominious,

monosyllabic Home. A slightly flabby NME rationalisation (5

June 1971) linked ‘the aptly-named Broken Barricades’ with

‘new directions in contemporary music’, claiming Procol had ‘broken down the

barricades presently surrounding rock’. That break-out image ran counter to the

title-track itself, whose lyric tells of flood-barriers breached, and baleful

forces compromising an erstwhile paradise by breaking in.

I asked Brooker if the title reflected Procol’s liberation

– having fulfilled a four-album contract – from fusty Regal Zonophone (his

musician father Harry Brooker’s label, a generation before). ‘That’s probably a

happy coincidence,’ he felt, ‘but Chrysalis were certainly more interested,

younger, more happening … and also on the way up.’

Chrysalis had been founded in 1968 by Chris Wright and Terry Ellis (‘Chris’ +

‘Ellis’ provided their company name). ‘Chris said to me, “I’ve just discovered

Procol Harum: you should get into them,”’ Terry Ellis recalls today. ‘A Salty

Dog was a revelation, nothing to do with Whiter Shade. We started

going to their shows as fans, and got to know the band. We said we’d like to

represent them, and were thrilled when they agreed. We all became friends.’

Chrysalis had an art

supervisor, whereas Keith Reid’s partner Dickinson had contributed the Zonophone

album covers, excepting George Underwood’s classic Shine on Brightly

(‘and that got chucked out by A&M,’ says Gary, no fan of the trite,

green-tinged substitute).

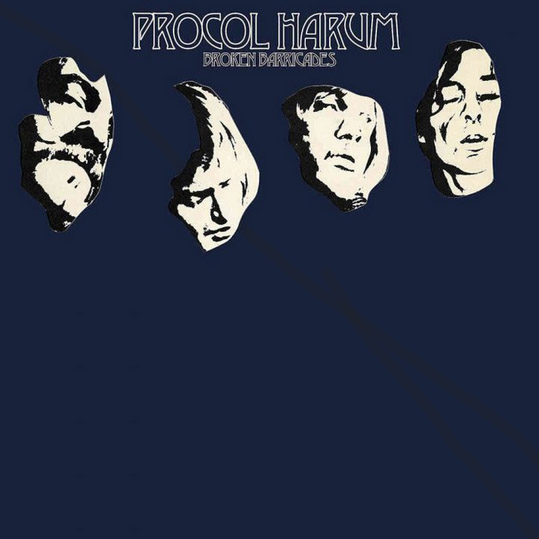

‘Barricades was a first, in design terms,’ says Brooker: four

sepulchral faces, hovering behind die-cut peep-holes, are revealed inside as

Procol’s musicians, pictured with instruments for the first time.

Their lyricist is

represented – starkly isolated from his alphabetically-ordered bandmates – both

by a portrait in negative and by four song-selections. ‘Reid chose those,’ Gary

told me. ‘He’d always been against having words on the sleeve, and when he

relented, it was only some of them.’ (Keith’s 1973

thinking, reported in Melody Maker, was that ‘my words must work on paper

as well as on the record. I couldn’t possibly do it any other way.’).

Brooker didn’t rate the

fun-and-games Home cover – ‘it didn’t seem to fit the dark

content’ – and his praise for its successor is pallid: ‘I had nothing against

it.’ He seems to feel the sleeves might have been better switched: Broken

Barricades, he notes, is the one with ‘mixed content’.

Brooker didn’t rate the

fun-and-games Home cover – ‘it didn’t seem to fit the dark

content’ – and his praise for its successor is pallid: ‘I had nothing against

it.’ He seems to feel the sleeves might have been better switched: Broken

Barricades, he notes, is the one with ‘mixed content’.

IN AMERICA

‘Procol’s career wasn’t going anywhere,’ says Terry Ellis, ‘and they were

frustrated. We were good friends with Jerry Moss, and started hounding A&M in

the USA to get behind the band properly, move their career in the right

direction.’

On 1 April 1971, as Procol began their tenth North American tour, A&M

grandiloquently announced that – acting on a ‘conviction that Procol rank well

within the top five of currently practising rock and roll bands’ – they were

planning to raise the band’s popular stature ‘to a position correspondent to its

artistic peerlessness.’

They issued an extravagant (now highly-collectible) promo box entitled

Procol Harum Lives: it contained a white-label copy of Barricades,

and five historic cuts showcasing a range of styles; a six-page biography; a

controversial band history by John Ned Mendelsohn; press-releases for the music

papers, trade and popular; group photos and performance shots; an article about

Reid’s song-words; and a studio recording of Mendelsohn interviewing Procol, who

sang, to Copping’s ponderous piano, Maybe It’s Because I’m a Londoner

(words and chords both oddly-remembered).

Though intriguing, this interview (transcript available at ‘Beyond the Pale’)

scarcely radiates the star quality A&M’s strapline ‘Procol Harum for the

millions!’ presupposed. Procol’s downbeat topics included lack of image, poor

management, legal hassles and press hostility. Likewise, when Brooker and Reid

were promoting Barricades during a radio spot with

WPLJ-FM’s DJ Alex Bennett, ‘They weren’t very forthcoming,’ as local musician

Ronnie D’Addario told me. ‘It was a tough interview, as I remember.’

It was a different story when, the following week, Bennett’s

poptastic

tones introduced Procol’s music to a potential eight million WPLJ listeners in a

concert broadcast from A&R Studios (the former Columbia premises on Seventh

Avenue in Manhattan). WPLJ was

New York’s

cool, free-form station; its name was no ordinary callsign, but an initialism

for White Port and Lemon Juice, the Four Deuces’ 1956 doo-wop number covered by

Frank Zappa

(‘What a silly lot they are, over there,’ Gary remarks, on learning this

etymology).

Procol certainly played brilliantly, to a studio audience that needed little

warming-up. Brooker remembers WPLJ as ‘… a good New York night, though it was

The Singer Show, and sewing machines were mentioned frequently: why wasn’t

there a Bacardi Rum Show we could’ve played on?’ Bennett’s commercial

responsibilities were clear: the last

minute of his valediction namechecks ‘Singer’ seven times, ‘Procol Harum’ but

once.

Gary’s civilised/peculiar patter during the ‘Procol Harum half-hour, or hour, or

hour-and-a-half’ must have fallen strangely on new listeners’ ears; but among

the cognoscenti, who recorded the broadcast, phrases like ‘mental blocks

are frequent’ quickly seeped into common parlance. ‘We’d be very honoured if

someone brought out a bootleg of us,’ Brooker told Hit Parader: but the

various WPLJ long-players – such as The Elusive Procol Harum,

with its mistaken track-titles Normie and Fare Thee Well – did

not reflect the band’s high standards.

IN EUROPE

In the UK Chrysalis waited until June to launch Broken Barricades,

‘an album that will probably sell a few measly copies in Britain and thousands

across the water’ in Melody Maker’s words. But live gigs were on hold, at

this crucial time, while Procol replaced Robin Trower, who had embarked on his

solo path to axe-hero status.

‘Robin came to me,’ Terry Ellis remembers, ‘and told me he was leaving Procol:

“We’re not really getting anywhere,” he said.’ Ellis had just bought a Jaguar;

knowing Trower admired that marque, he took him into the country for a drive. ‘I

told him he was making a terrible mistake; we had A&M fully on board, and the

future was going to be everything he dreamed of.’ But Robin remained resolute.

‘He had some new music on cassette,’ says Ellis, ‘and it was great. “I still

think it’s the wrong move,” I told him, “but if you go, we’d like to have you on

Chrysalis”.’

Newcomers Alan Cartwright (bass) and Dave Ball

(guitar) made their Procol début on 30 July in Phoenix, Arizona (a

briefly-contemplated reunion with organist Matthew Fisher – see press clipping

on page 15 – had quickly fizzled to nothing). Cartwright had been at school in

Edmonton, North London, with BJ Wilson; Ball, a Brummie, had blagged a Procol

audition by dint of charming the secretaries at Chrysalis after the

eighty-strong list had closed (Mick Grabham, another tardy hopeful, but boasting

less chutzpah, got his Procol break when Dave himself left). Ball was a Clapton

and Otis Rush fan: his breezy vitality was endearing, but he knew little of

Procol’s work. Fans didn’t give him any grief, Dave told Italy’s Radio Azzurra

(1999), though ‘one or two in the press might have preferred Robin’s style.’

Some US fans apparently ‘didn’t even notice that he’d gone: I don’t know whether

to be flattered or not!’

The new line-up’s first London concert (17

September, Queen Elizabeth Hall) garnered some reactionary press. Disc

and Music Echo ‘mourned the passing of the sophisticated Procol,’

claiming that ‘raucous guitar work … reduces them

to the level of other bands around who rely on noise rather than skill.’ Steve

Peacock, in Sounds, noted ‘moments of crass insensibility [sic] to their

music’ from Ball and Wilson. His intended criticism, that Wilson ‘thrashed about

like an octopus in a hot bath,’ proved to have legs: it has been quoted –

approvingly – by BJ fans ever since.

Procol Harum’s Sounds of

the Seventies BBC session – recorded in Studio T1, Kensington House,

Shepherds Bush – allowed a nationwide public to draw their own conclusions.

Margaret Ball, who logged her son’s gigs, noted 6 October as ‘John Peel’: in

fact their host was the likewise influential ‘Whispering’ Bob Harris, who rated

Barricades ‘my favourite album of the year’ and quietly championed

its title-track. Procol’s four Radio 1 offerings (three new, one old, aired on

25 October) left fans reassured. Mainland Europe followed on Margaret’s list:

between recording TV concerts in France (Pop II, 11 October) and Germany

(Beat-Club Workshop, 25 October) Procol entertained their fervent fanbase

in Denmark, Norway and Sweden, where this collection’s CD C was recorded.

Procol Harum’s Sounds of

the Seventies BBC session – recorded in Studio T1, Kensington House,

Shepherds Bush – allowed a nationwide public to draw their own conclusions.

Margaret Ball, who logged her son’s gigs, noted 6 October as ‘John Peel’: in

fact their host was the likewise influential ‘Whispering’ Bob Harris, who rated

Barricades ‘my favourite album of the year’ and quietly championed

its title-track. Procol’s four Radio 1 offerings (three new, one old, aired on

25 October) left fans reassured. Mainland Europe followed on Margaret’s list:

between recording TV concerts in France (Pop II, 11 October) and Germany

(Beat-Club Workshop, 25 October) Procol entertained their fervent fanbase

in Denmark, Norway and Sweden, where this collection’s CD C was recorded.

Numerous Swedish towns have a Folkets Hus (‘House of the People’), a

gathering-place originally associated with the labour movement. Stockholm’s

example (opened 1960) resembles unassuming city-centre offices, but contains two

auditoria; the larger, where Procol played on 16 October, accommodates about

760. Their show was co-promoted by Thomas Johansson, much associated with the

band in the 1970s. Hooked

since hearing Whiter Shade in Paris with The Move, Thomas first saw

Procol at Gothenburg’s Cue Club; decades later he still remembers them fondly,

especially ‘Keith, with his Mickey Mouse watch’.

Sveriges Radio (Sweden’s national broadcaster) recorded rock shows at various

venues (Procol’s

Stockholm Circus

concert in 1992, for example) and remixed them for broadcast. Back in

1971

the capital’s prestigious Konserthuset was unavailable, due to reconstruction

work (though 1975 saw Procol play there, and the Trower trio made a

high-charting live album

of their own Konserthuset broadcast).

The unsettled sound at

Procol’s Folkets Hus show was atypical, Johansson reckons; regrettably it

obliged Sveriges Radio to scrap certain tracks, as noted below.

ON THE RECORD

SIMPLE SISTER

During five years’ touring Procol Harum had played alongside many famous acts,

and been exposed to many influences. Their monumental Simple Sister

[A01], often introduced in concert as ‘our heavy-metal number’, originated,

Brooker now states, as ‘an I’ll-put-you-off-heavy-guitar sort of riff’. Procol

didn’t rate ‘the heavy inevitables’, as A&M called

the early Seventies’ vogue bands. BJ Wilson, once fancied by Page and Plant as

drummer for their nascent supergroup, told a 1971 interviewer that Led Zeppelin

were ‘rubbish’; and Robin Trower, in our 2019 conversation, declared Purple,

Sabbath et al ‘not my cup of tea.’ As for the vocal style, Gary had no

time for ‘doing that screamy thing all night, injecting steroids before you go

on.’ Recalling favourite bands Procol shared stages with, he lavishes most

praise – ‘they made a miraculous racket!’ – on Teegarden & Van Winkle, ‘two

country boys in dungarees’, seated at drums and organ respectively, not a guitar

in sight.

Nonetheless, a monster riff

kickstarts Broken Barricades : surprisingly it

originated on Brooker’s piano, though ‘he knew it would be for guitar,’ Robin

told me. Copping’s bass style is unmistakable. With four musicians

covering five instruments, Procol’s organ-quotient, already waning in the

Salty Dog era, plummeted. When Hammond is audible on Barricades

tracks it’s just glimpses, mere rock-pool reminders of a once-swollen tide.

In another strongly-felt

change, Brooker’s writing is simpler: several new songs rely on only one or two

four-bar chord sequences, frequently repeated. Touring, and attending to

business, had eaten into composing time, but once in the studio – arranging and

playing – his attention to detail revived. For Simple Sister he envisaged

a haunting sonic build-up, akin to the musical storm in 1970’s Whaling

Stories. Though Chris Thomas was at hand with AIR’s

three-suitcase Moog synthesiser, Gary

laboriously achieved the desired effect on piano, slowing the tape-speed and

multi-tracking the shifting notes an octave below their eventual playback pitch.

Brooker’s arrangement for

strings and three trumpets (conducted by his future solo-album producer, George

Martin) also repeats small ideas: to assess its cumulative effectiveness,

however, listen to A09’s pre-orchestral mix. Most

Procol borrowings from ‘serious’ music draw on European Baroque or Romantic

traditions, but Simple Sister’s repetitive layering recalls the

contemporary Minimalism of Steve Reich and Philip Glass. Procol’s reiterations

are leavened with well-planned irregularities: Brooker and Copping, both

dot-readers, coordinate their varied turnbacks in the break-down section (a

descendant of The Capitols’ 1966 single, Cool Jerk) by reference to a

written score.

BJ Wilson was a volcano of

variation, both within songs and from performance to performance: his work on

B04, B13 and C07 sparkles with joyful inventiveness. These live outings lack the

thrilling ‘Cool Jerk’ build-up, which was not reproducible in concert.

The five-piece versions offer strong organ by way of compensation. Procol’s

established rig – tonewheel Hammond and Leslie

cabinet – gives organists a head start if they want to imitate the band’s

classic sound; guitarists face a trickier problem, since Trower’s particular

sound resided in his fingers, not in any chosen guitar, amp or effect. Wisely

Dave Ball does not attempt the impossible, but turns in a characteristic,

vigorous performance.

Engineer Punter nicknamed this song ‘Pimple

Blister’,

reflecting Reid’s unsavoury text. In few words, plain and undescriptive, it

splices misogynistic cruelty with inexplicable pettiness, perverse themes that

later tracks will revisit.

BROKEN BARRICADES

Broken Barricades,

on the other hand, is verbally elaborate, delicate as well as hard-hitting. ‘I

find that lyric very interesting,’ Gary told me. ‘I’m not quite sure what’s

broken, but things are getting polluted and ruined.’ He responds emotionally to

Keith’s imagery, while singing, but ‘I don’t have a thought for every line.’ His

classy setting [A02] stands out from the album’s other compositions. ‘It was

written at the same time,’ he told me, ‘just more thought-out.’ Unusually for

Procol it harbours a middle-eight, in which Gary’s Fender Rhodes underlies four

riddling ruminations, perhaps exploring griefs personal to the band. The

resulting micro-dose of optimism – the final verse’s ‘brave words’ – has moved

many listeners, including Rock’s Anne-Marie Micklo, for whom it shored up

‘a sorely-lacking conviction that it was worth going on’ (July 1971). The UK’s

Record Mirror (19 June) judged this composition

‘one of their best’.

BJ Wilson stars in the playout (engineer Punter, himself a drummer, records the

kit vividly), alongside two Moog tracks, panned left and right; some unintended

pitch-drift adds to the mesmerising effect. The Minimalist influence is again

apparent, though on A10 we hear BJ interrupt the pattern with a new rhythmic

motif.

In live shows Copping’s right-hand Hammond took the Moog line; at WPLJ [B08] his

left hand plays an

early-Sixties Fender Rhodes Piano Bass – a cut-down electric piano, voiced to

imitate the pitch-range of a bass guitar – which

Procol called ‘The Fart Machine’. Alan Cartwright, well-versed in Tamla and Stax,

had heard this live ‘and the sound had seemed to be wrong’; the BBC track [B15]

shows him putting things to rights.

WPLJ-era fans were still attuned to the ‘classical’ Harum sound;

symptomatically, promoter Bill Graham had selected

The Winter Consort – featuring ’cello,

English horn, and soprano sax

– as support for Procol’s Fillmore East show eleven days later. ‘We were

thrilled,’ Paul Winter told me. ‘No band like ours had played the Fillmore

before: Procol were my favourite rock group after The Beatles, and their

classical dimension – always harmonically interesting – made for a good match.’

A Fillmore reviewer spotted that ‘the old Procol

sound was present in ‘Buttered Barricade’; the new titles were unfamiliar

to US audiences until A&M released Barricades (c/w Power Failure)

on single in May 1971 (the edited A-side lasting barely 140 seconds).

MEMORIAL DRIVE

Chris Copping’s tremendous bass guitar feel is exemplified on the rocking

Memorial Drive [A03] and on the WPLJ curtain-raiser [B01]:

like BJ on drums, he knows where to leave holes. Trower’s guitar is similarly

economical; his soloing on A12 may be a fleeting arrangement idea,

or just a spontaneous jam

from four musicians who enjoyed playing together (as ‘Liquorice John Death’

they’d recorded 1970’s legendary all-night session – released in 1998 as

Ain’t Nothing to Get Excited About – recreating The Paramounts’

repertoire with which they’d all paid their dues in the early Sixties). In the

event, it’s Brooker’s acoustic piano that handles the Memorial soloing;

and the live performance (albeit sans Fender Rhodes) sounds much like the

record.

‘I didn’t try to reproduce the actual sound of the album,’ Robin told me. ‘I try

to get a good sound in the studio, and a good sound live, but the two things are

different.’ BJ’s live magnificence shines out in the transition from the solos

into the final vocal. A11, with its harmony voices, suggests a half-hearted

attempt to elaborate the live studio performance – was this what Chris Thomas

meant by ‘fooling around’?

‘I didn’t try to reproduce the actual sound of the album,’ Robin told me. ‘I try

to get a good sound in the studio, and a good sound live, but the two things are

different.’ BJ’s live magnificence shines out in the transition from the solos

into the final vocal. A11, with its harmony voices, suggests a half-hearted

attempt to elaborate the live studio performance – was this what Chris Thomas

meant by ‘fooling around’?

A&M’s advertising painted a Procol ‘slightly more cerebral, more disposed to

darkness than the competition’. The present lyric – another stab at Still

There’ll Be More’s female degradation theme – surely merits such cautious

apologetics. Perhaps the backward-looking title, Memorial Drive, helps

locate the song’s disquieting narrative –

‘sold … shipped … branded … crying’ –

in the past. ‘We can talk about slavery now,’ Gary suggests, ‘because we know

what it was, and what people went through.’ It’s one of few Trower compositions

Procol still play onstage: ‘The reason is probably that I sang it,’ Brooker

offers, ‘so it still sounds like it did originally.’

LUSKUS DELPH

A&M’s press release speaks of ‘Reid writing searingly

direct words’, but BJ Wilson, talking to Rolling Stone, warned

that Keith’s lyrics were ‘a few levels of

consciousness below the spoken word form, and it’s pointless trying to make

literal sense out of them.’ Reid’s elusive coinage, Luskus Delph [A04],

appears to support BJ’s view, but Gary has ‘unpacked’ the neologisms on various

occasions, most persuasively as phonic amalgams of ‘lust/suck’ and ‘demon/elf’.

Keith himself told me (February 2019) the title was ‘me being impressionistic,

attempting to form sounds that refer to the woman I’m writing about’. Monet and

his fellow Impressionists sought, in addition to figurative depiction, to mimic

the quality of light given off by their subjects; what more natural, for a poet,

than to pursue a parallel ideal in sound? The searingly direct Reid added that

he’d ‘wanted to write about sex without actually saying “I want to fuck you,” or

whatever.’ ‘Widow’s crack’, he advises, is ‘me trying to summon a vaginal

image.’

Gary remembers first reading this lyric, realising

‘I know

what a lot of these things are!’ Disliking the ranting explicitude of Zeppelin’s

Whole Lotta Love – ‘every inch of my love’ etc – he matched his decorous

Luskus setting to ‘the gentle title’, which called to mind ‘some little,

good spirit.’ It’s another simple, yet delightful,

conception – two four-bar chord patterns, in alternating keys – and again much

elaboration was heaped on the bare rhythm track. ‘Luscious Delph’ on the

1970 tape already has strings in place, but two vocals are audible throughout.

‘Luskus Delphi’ [A13] preserves an earlier attempt to marry text

with tune, while noodling organ and Rhodes quavers search for the appropriate

mood and texture.

There’s no Luskus Trower in the vaults: ‘Usually I chose not to play a

song if it didn’t need guitar, if it wasn’t that kind of thing,’ Robin says now.

The arrangement is sensually completed by Brooker’s smooth oohing, and melodic

Moog. Gary liked the synth – ‘full of sounds nobody had made before’ – but

deployed it so unostentatiously here that most fans took it for a flute. Two

Moog-only tracks are listed on the 1970 tape box: #1 is a meandering A♭

waltz sketch, perhaps a Brooker original, which –

foreshadowing the close of

1973’s A Souvenir of London – ends after 140

seconds when Gary laughingly calls ‘I haven’t finished yet!’.

‘Peter Gunne’, recorded in March 1971,

features some seven dozen iterations – Minimalism again! – of Henry Mancini’s

riff. Brooker soon bought himself an ARP, ‘like a Moog, but a different make’,

and took to ‘messing around on that.’

The WPLJ Luskus Delph

[B05] uses Trower on bass, and Copping orchestrating from the Hammond; the song

has dropped a semitone since the recording. The

ritardando ending, and the A minor seventh end-chord, are familiar from the

Edmonton album; it’s surprising this song wasn’t played at

Folkets Hus in the run-up to that concert recording.

POWER FAILURE

Pounding

drums, tumbling piano chords, and guitars that roar like sparring lions across

the stereo field: side two of Barricades opens thrillingly,

ushering in a sparkling set of words about travelling band-life. A single

twenty-second musical sequence

occurs again and again (the final two verses are literal tape-clones) echoing

the cumulative effects (‘climbing’

… ‘crashing’ … ‘keeping’) in Reid’s writing. This undeveloped music is

‘just

a bit of tempo,’ according to Gary. ‘To me “Power Failure” literally

meant drum solo, end of story.’ He recalls various gigs when BJ kept Procol’s

audience enthralled while the crew strove to restore tripped electricity to a

blacked-out stage.

Wilson duly recorded a solo;

then – as

with Brooker’s chattering pianos on Simple Sister, and Trower’s massed

guitars on Song for a Dreamer – AIR’s sixteen tracks tempted him to

compile something larger than life. Had Procol hankered for such overdub-fests,

back in four-track days? It was pointless, Gary told me, to long for what was

unattainable ‘unless you were The Beatles, bouncing sounds to-and-fro under the

utmost supervision, so as not to lose quality.’ Most bands needed to be

thriftier with money and time.

Power Failure

[A05] is an uneasy artifice.

BJ’s overdubbing – tabla, shakers, various small percussion – creates a solo not

even an octopus could have played;

the grafted-on applause (perhaps a nod to Pepper-era

Beatles, introducing ‘Billy Shears’) suggests stage power has returned, but

paradoxically it never credibly failed (the guitars played on); and no live

performance could fade out so smoothly. Does Wilson’s hollered ‘Rubbish!’ (2:51)

mirror the Beatles’ laughter following Within You Without You,

pre-empting criticism of an experiment the band felt ambivalent about?

‘BJ kept slipping from 5/4

to 4/4,’ Brooker explains, ‘which is what he wanted to do, otherwise it wouldn’t

have been much of a challenge. But finding where the one is … I did

challenge him a couple of times.’

A14 spares us the pretend audience; but for genuine, unvarnished

drum-solos we have the concert versions [B12, B16, C05], where

the visceral genius of ‘Ravious Wislon’ makes the studio solo seem cerebral and

stiff. Critics who felt Procol had succumbed to a trendy performance-gimmick

overlooked the way this number doesn’t merely contain a drum-solo, it’s

about one, and uses it to symbolise touring entropy. Social

structures, sexual habits, dietary health, accommodation and transport

arrangements are in jeopardy: all roads lead to Power Failure.

Arguably the vinyl expression

of this subtle conceit suffers from the very ennui it seeks to portray;

ideally Procol might have

road-tested Power Failure rather than creating it in the studio. Live,

there’s terrific band detail: churning organ,

thundering bass, Copping’s rhythm guitar and vocal harmony. The

insistently-cycling structure becomes hypnotic: we’re transported by imagined

lights and vicarious adrenaline; ribcages throb as BJ’s kick-drum pounds on the

doors of the heart.

SONG FOR A DREAMER

‘BJ Wilson’s drumming is unremarkable for the first time since Shine on

Brightly.’ Thus the provocative Rolling Stone (June 1971),

referring not to Power Failure but to the new album’s underrated

masterpiece, Song for a Dreamer [A06]. In 1971 Keith Reid selected four

Barricades lyrics for the gatefold cover, and, in 2000, four for

his anthology, My Own Choice: three of the choices are identical, but

Broken Barricades is displaced in the book by Song for a Dreamer. ‘I

haven’t listened to the album in years,’ Keith told me, ‘but that one, I call it

up on YouTube from time to time: a wonderful, wonderful track.’ Pressed to

nominate his own favourite, Gary mentions Simple Sister (‘It came out

just how I hoped’) then adds, ‘But actually, I really like Song for a Dreamer:

so swimmy, a swirling pool of … something.’

Procol mythology suggests that, after Jimi Hendrix died (18 September 1970),

Reid was writing in one room, Trower in another, independently producing the

serendipitously-matching words and music that constitute the present tribute.

Unusually, the Procolers I consulted all agreed about the song’s genesis … but

not about the myth.

Procol mythology suggests that, after Jimi Hendrix died (18 September 1970),

Reid was writing in one room, Trower in another, independently producing the

serendipitously-matching words and music that constitute the present tribute.

Unusually, the Procolers I consulted all agreed about the song’s genesis … but

not about the myth.

Procol’s history with Hendrix went back to the beginning. Reid: ‘We met him at

the Speakeasy, the first night we’d done Top of the Pops [25 May 1967]’.

Brooker: ‘We played Morning Dew, and Jimi liked that: he didn’t fancy

grabbing the guitar off Ray Royer, so he got the bass off sweet David Knights,

and played it upside-down.’ Reid: ‘[Hendrix] liked Procol; I took our first

album round to his place near Marble Arch: he called Robin ‘a young player with

a lot of fire’. Brooker: ‘I don’t remember Trower liking Hendrix that much.’

Trower: ‘I think I had his first album, but to be honest I was into Albert King

and Howling Wolf at that time.’

Procol’s 1968 song about ‘King Jimi’ prophetically places Hendrix before a

philistine crowd who ‘could not see the joke’. Gary jumps forward to 4 September

1970, Jimi headlining at Berlin’s Deutschlandhalle, Procol watching from the

wings. ‘His playing was superb, with

Mitch Mitchell

on drums and

Billy Cox

on bass; but the [4,000-strong] audience didn’t want to hear Hendrix being what

he was that year. Rob went absolutely spare, talking to himself, “Why are they

booing, what the fuck’s going on?”’ Post-gig, backstage, Keith found the ‘always

modest’ Jimi ‘very down’. ‘They’d just wanted him to burn his guitar,’ he

remembers.

Hendrix departed for the Isle of Fehmarn, his last show. Flying back from

Germany, Keith happened to meet Jimi’s manager, Jerry Stickles; they shared an

airport taxi and Reid dropped Stickles off near Lansdowne Studios on his own way

home to Holborn. ‘On Shaftesbury Avenue I saw the headline, “Hendrix dead”. And

I thought how Jerry’s life would change forever as he went into his house and

heard the news. A huge change, in those few seconds.’ Reid penned Song for a

Dreamer, not immediately, but ‘in tribute to Jimi’s spirit as I

experienced him’. The two men had written together, swapping lines in a game of

verbal ‘consequences’ (‘I find that paper from time to time. I never throw it

away.’). He found Hendrix ‘a very spacey kind of person’, and the lyric tried to

capture ‘the depth of sadness in him, suffering, turmoil, wanting to move on,

but imprisoned by his image.’

Referring to past Trower/Reid collaborations, Robin recalls devising pieces of

music, whereupon ‘Keith would throw some words at me and say “See if you can

make them fit”.’ Song for a Dreamer was ‘probably the only time he ever

came to me: he said he had some lyrics and wanted to do a Hendrix tribute. I

went and listened to a couple of his albums, studied a bit, to see if I could

kind of capture the vibe. I did absorb quite a lot, and he definitely became my

mentor when I left Procol. We played Dreamer in the early days of the

trio.’

Lyrically and musically Song for a Dreamer touches on the otherworldly

vibe of Hendrix’s 1983 … A Merman I Should Turn to Be, with its ‘take our

last walk / through the noise to the sea / not to die but to be re-born’.

Sounds (October 1971) applauded Procol’s ‘fine track with a little monologue

through it, echoes, a dream-like sequence’ and commented on the ‘tightly

controlled guitar passages.’ ‘Everything was done live,’ says Trower now, ‘apart

from the dubbed leads and vocals.’ Compare A06 and A15 to appreciate what Chris

Thomas brought to the overall effect: ‘a talented guy!’ in Robin’s words.

Procol’s rolling drums and distant Rhodes piano, Trower’s Leslified leads and

(sometimes) backward vocals, all make for ‘a very good piece’ in Gary’s words,

‘a great performance from the guys’ in Keith’s. And the stereo collapse about

five minutes in, as the treated guitars die away and Robin’s clean-toned Strat,

tuned to open E, rings out hopefully, is Chris Thomas’s master-stroke.

PLAYMATE OF THE MOUTH

BJ Wilson told Ritchie Yorke that Playmate of the Mouth [A07] was ‘one of

the tracks we have to cross out when we send our albums to our mothers,’ to

forestall a verdict that ‘“Keith Reid is getting more perverted every album”.’

Wilson told a similar story about Luskus Delph, the other pillar of

Procol’s Kama Sutra, likewise painted in metaphors both coy and lurid.

Speaking in 2019, Brooker is critical of Playmate. ‘Usually I try to find

a song that fits the words, but I don’t think this one is a great match.’

Readers are invited to swap partners, singing one song to the tune of another:

does the genteel Luskus music

sanitise some of the

Playmate lyric’s sleaze? Does Playmate’s cruder setting liberate some

of Luskus’s sublimated longings?

In addition to their shared

metre, both songs ride on four-chord patterns; one

has a plunging melodic shape, while the other’s contour rises, like the ‘baby

sandwich’ anticipating Passionata’s ministrations as she initiates the ash-robed

‘sceptic at the feast’. Brooker reported Reid’s shifting preoccupations

to Yorke: ‘Last year it was death, this year it’s sex … and violence.’ Maybe so,

but death is still strongly implied in images like ‘widow’s

crack’ and ‘funeral parlour’. In Playmate the language of romance – ‘old

and mouldy’ – is laid waste by the orgiast, ‘Savage Rose’. Her name occurs (‘at

the Arabian crossing … where Savage Rose & Fixable live simply in their wild

animal luxury’) in Bob Dylan’s 1965 liner note on Highway 61 Revisited,

the album that so influenced early Procol writing. ‘I must have read that,’

Keith told me, ‘but, hand-on-heart, it didn’t come from there.’

‘The Boyard’s

Ball’, doubtless a mishearing of ‘Voyeurs’ Ball’, is an early

song-name handwritten on master-tape boxes, spotlighting the first verse’s

role-playing debaucheries; whereas the replacement title, Playmate of the

Mouth, punningly slips oral sex into its evocation of the centrefold nudes –

Marilyn Monroe, in 1953, was the first – commodified monthly for Playboy

customers’ gratification. Reid’s ‘neon captions’, suggestive of

strip-club signage, underlines the song’s remoteness from romantic, personal

intimacy.

Trower’s dirty blues timbre nicely matches the

verbal tone, but Brooker protests that, though ‘the idea of the composition is

good, it didn’t ever go anywhere. It’s so boring, we never play it!’

Procol brought in ‘a couple of trombones and a trumpet’ to relieve the perceived

tedium with a touch of New Orleans. ‘It was hard,

getting that out of classical musicians,’ Gary remembers. ‘We did send them down

the pub at one point; but if it sounds as though they’re hanging loose, it’s

because of my ‘hang-loose’ writing.’ His skilful score includes all ‘the ad-lib

parts you’d expect from a Dixieland jazz-band, even a British one.’ ‘Fooling

about’, perhaps, but it works: the ‘naked’ track, A16, is audibly missing a

worthwhile dimension. The beaten-up bar-room piano sound was another trick.

Though Gary reports that ‘most good studios kept an out-of-tune piano, in case

Russ Conway came by’, tape-op Michie remembers an upright being prepared

specifically for Procol’s use: ‘one of the three strings for each of the treble

notes was detuned a specific amount.’

Through such detailed,

labour-intensive work, the ‘boring’ song proved … ‘Fixable’. (Yet the team

didn’t ‘fix’ Brooker’s vocal which, though full of feeling, clearly betrays a

heavy cold; the 29 December recording – as well as being overdubbed with maracas

– signs off with a sneeze). ‘Apart from the playing, the sound and everything,

Playmate of the Mouth was probably the worst Procol track ever,’ is

Gary’s conclusion.

Through such detailed,

labour-intensive work, the ‘boring’ song proved … ‘Fixable’. (Yet the team

didn’t ‘fix’ Brooker’s vocal which, though full of feeling, clearly betrays a

heavy cold; the 29 December recording – as well as being overdubbed with maracas

– signs off with a sneeze). ‘Apart from the playing, the sound and everything,

Playmate of the Mouth was probably the worst Procol track ever,’ is

Gary’s conclusion.

POOR MOHAMMED

In 2019’s social climate the final Barricades track feels

problematic. ‘It wouldn’t have struck me, at the time, as anything

inappropriate,’ Keith Reid told me. ‘He’s an imaginary Arab and I certainly felt

sorry for him.’ Whereas the imaginary Arab in Song for a Dreamer is some

kind of ethereal helmsman, Poor Mohammed [A08] is an earthly victim of

hellish spite and degradation. ‘It was a portrait of savagery and cruelty, me

playing with language to create feelings,’ Keith says. ‘I wasn’t concerned with

literal meanings.’ Gary calls this ‘a good way of writing, to observe, then put

the listener in that position’, yet he declined to sing the number. ‘It didn’t

seem my kind of thing. Robin sang the demo, and it sounded all right. He’s got a

lot of soul: he can really put an idea across vocally.’ But what idea, exactly?

Trower’s recollection is of ‘a very strange lyric: I can’t make anything of it,

to be honest.’

On Procol Harum Lives Keith ventures that ‘as a writer you’ve

given of yourself … to people that are strangers. They’ve got a strong

understanding of you.’ But in 2019 he admitted ‘It was only much later I came to

realise people might associate these songs with my actual thoughts.’ The album’s

multicultural imagery – Arab, Mexican, Turkish, Zulu – is apparently nothing

conscious: ‘It may appear as a theme, but it’s just the effect of background

work in the mind.’ Such willing trust of his own subconscious, and healthy

indifference to popular trend, are hallmarks of

‘the outstanding lyricist of his generation’, as Terry Ellis terms Reid now.

Rolling Stone

found Poor Mohammed ‘the first noteworthy cut on the whole second side,’

and

to A&M themselves it was ‘the album’s obvious choice for a single’. Its sound

(even easier to admire on A17) is exemplary, from the subliminal maracas to

Trower’s steel, singing on his Les Paul frets (‘I

didn’t really play slide,’ he told me, ‘I just thought it would be nice for this

one.’). But 1971 saw no chart smashes. As Ritchie Yorke explained (July

1971), ‘Procol is simply too good for the

often moronic tastes of the people that program Top 40 radio in North America.’

Mohammed

was Robin Trower’s valedictory Procol statement (until he contributed to 1991’s

The Prodigal Stranger). Whereas early Procol albums

typically end with stirring instrumental passages, this was an

85-second, single-chord anti-climax. Brooker,

sparsely represented on the track, says ‘It doesn’t do much, does it?’ and now

concedes that Song for a Dreamer might have made a more fetching finale.

‘We could reissue the album that way,’ he says, ‘but there’s something to be

said for leaving it: if we were wrong, we were wrong.’ Chrysalis were at fault

too, he feels, lacking the experience to bring out their artists’ best. ‘They

should have said, “We haven’t got the big one here, something radio will play,”

and pushed us for something a little bit commercial.’

Huge commercial success beckoned for Trower, and Barricades

was his springboard to stadium stardom. ‘I always thought of Procol as my

schooling,’ he told me. He hadn’t suffered from George Harrison syndrome – his

own material sidelined by more established writers – he’d been ‘fundamentally a

lazy musician in Procol Harum. I wasn’t ambitious, nor frustrated. I just

realised finally that the most fun would be writing my own stuff and having my

own band.’ Gary feels that Robin underrates his Procol career: ‘His playing –

even when he wasn’t sure of the chords and just went ‘pwwonnnng’ – really

added something, and started something different.’ ‘Once I got into my

own three-piece,’ says Robin, ‘I had to up my game quite a bit. But I really

enjoyed doing Broken Barricades: there’s a lot of potent stuff on

there, great confidence in the performances; it was my favourite album with

Procol.’

LEGACY TRACKS

Matthew Fisher’s Repent Walpurgis [C10] is the earliest ‘legacy track’ in

this collection. 1971’s restoration of a full-time organist allowed some of

Procol’s statelier numbers to emerge from hibernation: the Folkets Hus setlist

has a surprising half-dozen Fisher writing-credits, and none for the more-recent

departure, Robin Trower (whereas the WPLJ scoreline, six months earlier, was

Trower 3, Fisher 0).

Ball’s soloing here is relatively measured, if not as memorably tuneful as his

predecessor’s ‘compositional’ style. (‘Such great memories of Robin,’ says Terry

Ellis now, ‘a very special guitarist: you can’t replace him. Dave Ball was good,

but he wasn’t Robin.’). Erratic mixing muffles the start of Bach’s Prelude No

1 from The Well-Tempered Clavier (Book I) which Brooker

performs in full (as with the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra, 33 days later),

expanding the original excerpt by 100 seconds. The drum-punctuations separating

1967’s final chords blossomed into BJ’s later percussion solos; here they

provide a dramatic false ending for the live concert but, since Sveriges Radio

didn’t broadcast Repent, home audiences didn’t register the ensuing In

Held numbers as an encore.

In both

this collection’s live versions of Quite Rightly So Procol’s reflective,

between-verse dallyings interrupt the jaunty momentum of the original 1968

single; it’s still ‘one of the nicest things they’ve ever done’, according to

Whispering Bob’s back-announcement [B14]. Ball’s devil-may-care guitar break

exemplifies his remark, to Radio Azzurra, that ‘I very rarely worked anything

out … I just tended to play intuitively.’ He takes flight at the end, while the

chords shift (Homburg-style) over a static bass note: unusually for a BBC

session, producer Pete Dauncey fades the ending. But piano, organ and drums all

contribute to an emphatic rallentando finale at Stockholm [C04]; the song

is well received, though arch-fan Jonas Sjöberg recalls how non-specialist

Folkets Hus patrons would have preferred the earlier singles, Whiter Shade

and Homburg.

In the Wee Small Hours of Sixpence

[C01] was Procol Harum’s third B-side, and never saw album release. Despite its

attractive melody, mysterious verbal melancholia, and uncharacteristic, bright

key-change, it has rarely been heard in concert. Though the playing is sprightly

– Cartwright’s muscular bass stands out, BJ’s ending has energy to spare, and

the clarifying mix reveals Ball’s rhythm guitar prowess – this performance was

omitted from the broadcast.

At Sixties’ gigs, alongside

The Doors, Brooker had seen Rhodes Piano Bass used by organist Ray Manzarek to

supply ‘bottom end’; Gary’s future colleague Peter Solley worked similarly in

the Terry Reid trio. Peter – ‘still a proud Procoler’, as he described himself

to me – enjoyed that ersatz bassist role, and used a foot

control for his Hammond’s Leslie cabinet, so his left hand could remain on the

Fender (‘clunky machine, shitty action’). Chris

Copping had been lauded as a more exciting bass-guitarist than his Procol

predecessor Dave Knights, whose lines too often followed Brooker’s left hand:

yet arrangements that needed Chris’s ‘Fart Machine’ – like Shine on Brightly

– obliged him to back-pedal, translating inherited basslines back into

piano technique. As well as misdirecting his talent, this hampered

drawbar-tweaking and other Hammond finesse. For Solley or Manzarek, playing two

separate keyboards presented little problem: like any pianist, they effectively

had a brain in each hand. Arguably Manzarek’s left-hand style didn’t sound like

a real bass-player anyway, but in the case of Copping – an expert bona-fide

bassist – his hands wanted to think not just in two parts but also in two

distinct idioms.

The two versions of Shine on Brightly here

allow us to compare four- and five-piece approaches to this 1968 title-track. At

WPLJ [B06] we sense constraint; in Sweden, liberation. Gone is WPLJ’s dutiful

recreation of Fisher’s elegant organ-break; Chris forges something vibrantly new

in the moment. The new guitarist is also liberated: whereas Trower’s Morse-like

monotony was a disciplined compositional element, Ball modifies the line with

personal touches.

Though judged unfit for

broadcast, the Swedish version is interesting. Until the sound-crew retrieve

Gary’s awol vocal, BJ is our prime ear-magnet, maintaining a brilliant level of

impudent originality. ‘I like to be rude when I play,’ Wilson told Melody

Maker in 1973. ‘I put all the energy I’ve got into playing.’ In the same

feature Alan Cartwright explained that ‘we can’t get a perfect sound on stage …

we’re using an amplified acoustic piano and an organ, and the difference in the

sound levels makes for technical problems.’ Luckily Brooker could call on

producer Chris Thomas, at Folkets Hus, to resolve issues as they arose.

[Nonetheless, as we go to press, Esoteric Records has

decided against releasing the flawed Shine on Brightly discussed above.]

Though judged unfit for

broadcast, the Swedish version is interesting. Until the sound-crew retrieve

Gary’s awol vocal, BJ is our prime ear-magnet, maintaining a brilliant level of

impudent originality. ‘I like to be rude when I play,’ Wilson told Melody

Maker in 1973. ‘I put all the energy I’ve got into playing.’ In the same

feature Alan Cartwright explained that ‘we can’t get a perfect sound on stage …

we’re using an amplified acoustic piano and an organ, and the difference in the

sound levels makes for technical problems.’ Luckily Brooker could call on

producer Chris Thomas, at Folkets Hus, to resolve issues as they arose.

[Nonetheless, as we go to press, Esoteric Records has

decided against releasing the flawed Shine on Brightly discussed above.]

Flashes of exuberant banter alternate with some poignant material during the

Swedish recital.

The

innocence of Magdalene (My Regal Zonophone) [C08] mimics the

Shine on Brightly original; the patent piano/organ blend, and Boys’

Brigade snare-work, leave little space for Ball’s guitar, which struggles to

find a worthwhile toehold.

Just a month after Folkets

Hus Procol Harum were in Canada, rehearsing for their iconic concert with the

Edmonton Symphony Orchestra: it’s no surprise that so much of 1968’s In Held

’Twas in I graced setlists earlier in the tour. These are not just intricate

songs, they involve complex transitions: In the Autumn of my Madness

[C11a] is two pieces in itself: the mournful Fisher ballad, and the heavy

instrumental reprise of Brooker’s wordless Held Close theme, prefaced by

the Trower riff, which Cartwright and Ball deliver spectacularly at Folkets Hus.

Gary doesn’t nail all the fearless high notes in Look to Your Soul

[C11b], but Wilson pulls off some brazenly bizarre fills. Keyboard work in

Grand Finale [C11c] suffers from the wayward mix, but the climax is

cathartic, the band reluctant to let go. Procol also filmed this abridged In

Held for Radio Bremen’s Beat-Club Workshop nine days later, footage

first seen in Esoteric’s fiftieth-anniversary boxed set, Still There’ll be

More.

‘Five new songs out of

twelve [played at WPLJ] is quite a heavy contribution from the new album,’ says

Brooker now. ‘It’s a broadcast, not just some gig: you had to think a bit

commercially.’ Hence, no doubt, the inclusion of A Salty Dog, 1969’s

chart hit manqué. B10 is not the most convincing version, however:

wavering intonation, drama somewhat muted. The ‘bottom end’ is Robin on bass

guitar, not something he’d used in other bands (‘He often played it like a

guitar,’ says Gary, citing Dead Man’s Dream). At Folkets Hus, however, a

feeling and flexible performance [C09] is rapturously applauded.

Juicy John Pink

[B09] is the most-played of three Trower co-writes on the Salty Dog

album, more various even than his trio of Barricades

contributions. Originally recorded with minimal instrumentation, it benefits

here from drums, and gradually-added bass and piano. Reid’s words feel like

timelessly-authentic blues, whereas Trower’s generic twelve-bar sequence

features occasional first-inversion subdominants, and diminished substitutions.

The ‘little folk song’ [C03] from A Salty Dog – given the

portmanteau mis-title ‘All This and Be More’ for the night – was

being readied for its orchestral Edmonton outing, by which time

Dave’s lyrical countermelody would decorate the final verse only. This

performance, despite its firm rubato, sounds over-excited; its Canadian

airing, however, is poignantly reflective, as Keith’s libretto requires.

Pilgrim’s

Progress [C06] has outlived the departure of composer Matthew Fisher (‘taking

with him, to the relief of many, the omnipresent liturgical organ’ according to

Jon Mendelsohn’s promo aforesaid). In Copping’s (two) hands the Hammond enters

later than it did in 1969, making the song less like

a ‘junior’ Whiter Shade (Mendelsohn again); yet Brooker’s inimitable

voice, taking over (and re-shuffling) Reid’s narrative, does enhance a passing

resemblance to Procol’s famous début, which the band declined to perform at this

era.

‘With Whisky Train, Gary said, “Come up with a guitar riff, and we’ll see

if we can write a song round it”,’ Robin told me. So arresting was the resulting

guitar statement, which

opened Home, that Procol re-used the trope a year later, asserting

Trower’s burgeoning dominance right from the start of Broken Barricades.

Yet Rolling Stone (June 1971) reckoned Robin’s part, both

‘solo space and general role’, was ‘much smaller than on past albums.’

The hurtling WPLJ Whisky

Train [B11], driven by BJ in ‘octopus’ mode, epitomises high-energy

four-piece Procol: high subtlety too, as witness the telepathically synchronised

drop-outs around 2:37. Not until Geoff Whitehorn’s time did this song become a

Procol standard again.

The aforementioned

Rolling Stone article ranks Still There’ll be More, ‘organ-less and

worlds less pompous than the PH of the past’, among ‘the huge list of their

best’. Dynamic, classy performances from all four musicians on B02 carry the

WPLJ crowd before them. Somehow the flat-out five-piece version [C02] emanates

effort over achievement, though one cannot fault the bass/drum synergy from

friends reunited Cartwright and Wilson. Everyone survives BJ’s ‘rude’

risk-taking before the second guitar-break, and the Swedes warm to Ball’s

blustering, so different from Trower’s serpentine counterpoints. ‘Pedal or

skin?’ asks Gary at the end, suggesting that – perhaps unsurprisingly –

something has broken in kick-drum land.

Nothing that I Didn’t Know [B03] follows Still

There’ll be More in Home order, a second exploration – starkly

contrasting – of female fragility. Copping’s solos ‘are effective because they

are so modest, like a George Harrison guitar solo’, in novelist Sebastian

Faulks’s words. A last-minute major chord from the piano brightens the dying

moments of this lament, which is not really ‘Scottish’ (nor was its broadcast

heard by ‘fifty million people’ – a quarter of the US population – though one

printed book seemingly takes that throwaway Brookerism literally).

Whaling Stories

in performance has often attracted bolt-on instrumental preludes; the 70-second

intro to B07 comprises a fragment of Oh Yeah-era Mingus, some generic

Procol funk, a jazzy Brooker original dating from Home rehearsals

(Gone to da Country to Rethink da Music as he now titles it), and ends

with the album-version’s opening bitonal chords, suitably disguised. This

crazy-paving preface developed, on the road, as early as July 1970; otherwise

little has changed since the Home album. Trower plays

expressively, his tone majestic; Brooker sings passionately (note especially

‘bloodhounds’!); Copping’s simultaneous bass and organ underpin the ensemble.

Wilson is the perennial wild-card: the cowbell soliloquy following the 5/4

chords, the terrific fill preceding the ‘final scream’. Fans who consider

Home an

unrivalled masterwork may be startled by Robin’s recent disclosure that he

‘didn’t really like that album a lot … I’m not sure we had it together great …

but it did lead up to Broken Barricades’.

CELLARFUL OF DIAMONDS

CELLARFUL OF DIAMONDS

And where did Broken Barricades lead? To the departure of Procol

Harum’s star guitarist, then – most unexpectedly – a top-twenty chart hit,

Conquistador, with Dave Ball, and an iconic gold album (Procol gave one gold

disc to Ritchie Yorke, who’d brokered the partnership that led to Live

with the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra). This anomalous album (containing

no new material at all) outsold the rest of Procol’s oeuvre, satisfying the

strident prediction A&M had made for Broken Barricades; it went to

#5 in the USA’s

Billboard

chart, whereas Barricades peaked at #32 (level pegging with

A Salty Dog), and hit the low forties in UK and German charts.

Then Ball left, having played some 120 Procol gigs, in nine countries – Hawaii

(under 1%), Norway (under 1%), Sweden 1.5%, Germany 3%, Japan 3%, Denmark 4%,

Canada 7%, UK 16%, and USA 64% – and begun recording Grand Hotel.

After joining Long John Baldry he served in the British Army, then worked in

computer programming. His Don’t Forget your Alligator (2012)

marked a return to the music business, sadly curtailed by his death in 2015.

With Mick Grabham on

guitar the Procols achieved enhanced stability, and their following pair of

albums contained nineteen fine Brooker/Reid songs, amply fulfilling Yorke’s 1971

non-definition of their unique selling point, ‘rock music which is virtually

indefinable because of its paradoxical intricacy and simplicity.’

Barricades tends towards simplicity but – as Gary’s ‘mixed content’

remark, cited above, suggests – every track is arguably an anomaly. The album

now stands as a definitive rebuttal of Nik Cohn’s brattish assessment, ‘As for

Procol Harum, they made one classic record, A Whiter Shade of Pale, and

then kept reviving it under different names and disguises until everyone got

sick to death of it.’ (Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom, 1969).

A&M’s prediction that

Procol would ‘become universally successful’ was optimistically misjudged, as

was the claim that Barricades would ‘inspire the listener not to

contemplate, but to leap atop his seat to whoop and boogie joyously.’ It was

not, ‘at long last, Procol Harum for the millions,’ yet the band has played to

millions since that time, inspiring contemplation and joyous whooping in

equal measure.

Not many fans rate the

present album – dark, puzzling, scary – an all-time Procol favourite, but it has

proved to be a ‘cellar full of diamonds’: three tracks sparkled at sold-out

London orchestral shows in the present decade; and half its songs were still in

the fiftieth-anniversary repertoire, in which respect it outweighs several

earlier albums. And at the time of writing, Procol Harum have just completed

their third triumphant back-to-back club gig here in Manhattan, wowing sold-out

audiences with the magisterial muscle they perfected on Broken Barricades.

They’ve never sounded better.

© Roland Clare, New York City, February 2019

Many thanks to Gary Brooker MBE, Keith Reid and Robin Trower, who gave fresh

interviews for this essay, and to Dave Ball, Chris Copping, and Chris Michie for

less recent assistance; to Terry Ellis, Thomas Johansson, Peter Solley and Paul

Winter for fruitful conversations, and to thoughtful fellow-fans Jacob

Cunningham, Ronnie D’Addario, Christoffer Frances and Bert Saraco; to Procol

scholar Frans Steensma for generously-shared research; and to Prof Sam Cameron,

my collaborator in the ongoing ‘Taking Notes and Stealing Quotes’ pages at

www.procolharum.com, to which readers are referred for more detailed

consideration of many of the songs discussed above.