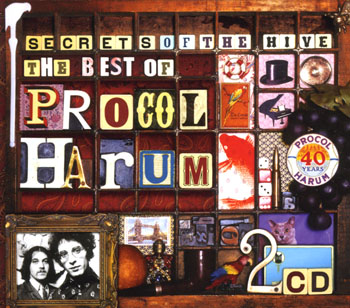

Procol Harum • The Secrets of the Hive

Patrick Humphries's liner note on the 2007 Compilation from Salvo Records

Strange though it may seem, there was

life to Procol Harum before A Whiter Shade of Pale … Emerging during the

mid-60s Beat Boom, Southend’s Paramounts – led by Gary Brooker – soon

established themselves as one of the leading R’n’B outfits of the day. And, in

the fullness of time, Procol Harum would be made up entirely of ex-Paramounts.

The Paramounts had first come to life in

the basement of the Penguin Café on the Southend seafront. The cellar of the

café, which was owned by guitarist Robin Trower’s dad, was converted into a club

called The Shades, where the Paramounts enjoyed a Sunday-night residency. A

further part of the club’s appeal came from the two well-stocked juke boxes, the

contents of which would form the foundation of the Paramounts’ set-list when

they began gigging away from The Shades.

At the very beginning, when they were

still playing in Southend, the Paramounts’ repertoire was very rock’n’roll. A

souvenir of that era, when Elvis, Fats Domino, Carl Perkins and Chuck Berry

dominated, can be found in the 1970 Procol Harum session recorded at Abbey Road

studios and eventually released as a fans-only CD, Ain’t Nothin’ To Get

Excited About, with the band credited as ‘Liquorice John Death’ (details at

www.procolharum.com). The more widely-available 1998 compilation of the

group’s best work at the legendary EMI studio, The Paramounts at Abbey Road,

also contains some tracks from that 1970 session.

Having

spread their wings and ventured inland, the Paramounts started playing the Ricky

Tick circuit – Hounslow, Windsor, Reading, Maidenhead, Eel Pie Island – which

had recently been outgrown by another promising R’n’B group, the Rolling Stones.

Despite their new-found success, the Stones had only good things to say about

the Paramounts, which helped the Southend outfit to land a record deal of their

own. The parallels were there for everyone to see when the first Paramounts

single was released: it was a version of Leiber and Stoller’s Poison Ivy,

which the Stones had also covered on their first EP.

Having

spread their wings and ventured inland, the Paramounts started playing the Ricky

Tick circuit – Hounslow, Windsor, Reading, Maidenhead, Eel Pie Island – which

had recently been outgrown by another promising R’n’B group, the Rolling Stones.

Despite their new-found success, the Stones had only good things to say about

the Paramounts, which helped the Southend outfit to land a record deal of their

own. The parallels were there for everyone to see when the first Paramounts

single was released: it was a version of Leiber and Stoller’s Poison Ivy,

which the Stones had also covered on their first EP.

The top

DJ on that circuit was Guy Stevens, who supplied

the Paramounts with the original American recordings they would then cover. ‘A

box of forty singles would arrive from America every week for Guy,’ Gary Brooker

still recalls wistfully. And with luck, the Paramounts got first pick, before

the Stones, Who, Kinks or Yardbirds could get their hands on them!

Poison Ivy

was the only Paramounts single to register on the UK charts (reaching #35 in

January 1964), but it was enough to ensure that they remained on EMI. In those

days, a 45 rpm single (A and B sides) was customarily cut in a straight

three-hour session. But the Paramounts found that ‘sausage factory’ approach to

recording deeply dispiriting, with the result, as Gary told me much later on,

that ‘we could never really get the sound on record that we got on stage’. That,

together with the fact that the Paramounts’ live outings were latterly confined

to backing Sandie Shaw or Chris (Yesterday Man) Andrews in cabaret, saw

the group’s enthusiasm flagging fast.

However, those Paramount days did

provide one last highlight – the historic final Beatles UK tour in December

1965, for which the Paramounts were the opening act. They appeared along with

the Moody Blues and various acts from Brian Epstein’s stable (Beryl Marsden, the

Koobas). Forty years on, Gary still remembers that Beatles tour clearly: ‘we

opened it with or two or three numbers, and then we backed one or two other acts

– Beryl Marsden, Patrick Kerr – for their fifteen minutes. So musically it

wasn’t very satisfying. But we’d watch the Beatles from the wings, and you could

just about hear them above the screaming.’

By the summer of 1966 the writing was on

the wall for the Paramounts – and for many other similar groups. Bob Dylan, the

Beatles and the Stones were now all leading from the front. But by then, Gary

Brooker was also keen to lead rather than follow: ‘I was listening to Art Blakey,’

he told Will Birch, ‘smoking a lot of hashish and thinking about Charlie Mingus!’

The Paramounts finally split in the autumn of that year.

The story might well have ended there,

had it not been for the timely reappearance of the ubiquitous Guy Stevens. Guy

had known Gary during the Paramounts years, and had since encountered a boy

called Keith Reid, barely out of his teens, who wanted to be a songwriter. Guy

introduced the pair, and one fateful day Gary returned home to Southend with an

envelope full of Keith’s lyrics. The package remained unopened for weeks. But

eventually, after some not-too-gentle prompting from Keith, Gary propped the

lyrics on his piano … and one of the great British songwriting partnerships was

born.

Keith Reid had been writing lyrics and

hawking his demo tapes around the record companies since he left school at 15.

But he admits ‘I wasn’t getting much interest, until I went to Sue Records and

met Chris Blackwell. He wasn’t really interested either, but he said I’ve got

this bloke Guy Stevens who works for me ... go and see him. So I got chatting to

Guy, and he really encouraged me.

‘Somewhere in there I got frustrated and

felt I should go to New York. So I went to see Chris Blackwell again and said:

“I’ll give you my publishing if you give me the fare to go to New York!” He said

no, but go and see this bloke David Platz at Essex Music, and he signed me up as

a songwriter.’

The plan was always that Brooker and

Reid would be a songwriting team, backroom boys who supplied material to

established singers – an early effort, Conquistador, for example, was

intended for the Beach Boys; another for Dusty Springfield.

But with the dominance of the Beatles,

the Who and Stones, all of them self-contained units with no need for outside

songwriters, it soon became inevitable that for their songs to be heard, Brooker

and Reid would need to form a band of their own.

‘Gary and I had the idea of a whole

unique sound,’ Keith explained. ‘It wasn’t simply a question of forming a band

to perform our songs, there was this whole thing we were trying to achieve: we

were determined to have acoustic piano and Hammond organ, and the blues

guitar … we had the concept of a total sound, and A Whiter Shade of Pale

was the definition of that sound we were trying to achieve.’

Now they had the songs and the sound,

all they really needed was a name. And once again, it was Guy Stevens who rode

to the rescue, with Procol Harum – a name he had filed away (along with Mott the

Hoople and Spooky Tooth) for groups as yet unformed.

Early in 1967, a Melody Maker

advert ran: ‘Lead guitar, organist, bass wanted for new project with Y.

Rascals/Dylan type sound to develop new material.’ A demo tape of the new outfit

began circulating and soon reached the ears of producer Denny Cordell who, by

the time he came to produce Procol Harum, had already established his reputation

with acts such as the Moody Blues, Georgie Fame and the Move.

Once they were all assembled in the

studio, something magical occurred … ‘I remember at the time Salad Days (Are

Here Again) and A Whiter Shade of Pale were both worthy,’ Gary

told me. ‘But on the day, Whiter Shade just felt right. And the sound of

the records, and particularly the sound on A Whiter Shade of Pale, was

just absolutely right …”

The end result was one of the most

distinctive singles of all time. And the rest truly is history … .

More about this album

Having

spread their wings and ventured inland, the Paramounts started playing the Ricky

Tick circuit – Hounslow, Windsor, Reading, Maidenhead, Eel Pie Island – which

had recently been outgrown by another promising R’n’B group, the Rolling Stones.

Despite their new-found success, the Stones had only good things to say about

the Paramounts, which helped the Southend outfit to land a record deal of their

own. The parallels were there for everyone to see when the first Paramounts

single was released: it was a version of Leiber and Stoller’s Poison Ivy,

which the Stones had also covered on their first EP.

Having

spread their wings and ventured inland, the Paramounts started playing the Ricky

Tick circuit – Hounslow, Windsor, Reading, Maidenhead, Eel Pie Island – which

had recently been outgrown by another promising R’n’B group, the Rolling Stones.

Despite their new-found success, the Stones had only good things to say about

the Paramounts, which helped the Southend outfit to land a record deal of their

own. The parallels were there for everyone to see when the first Paramounts

single was released: it was a version of Leiber and Stoller’s Poison Ivy,

which the Stones had also covered on their first EP.