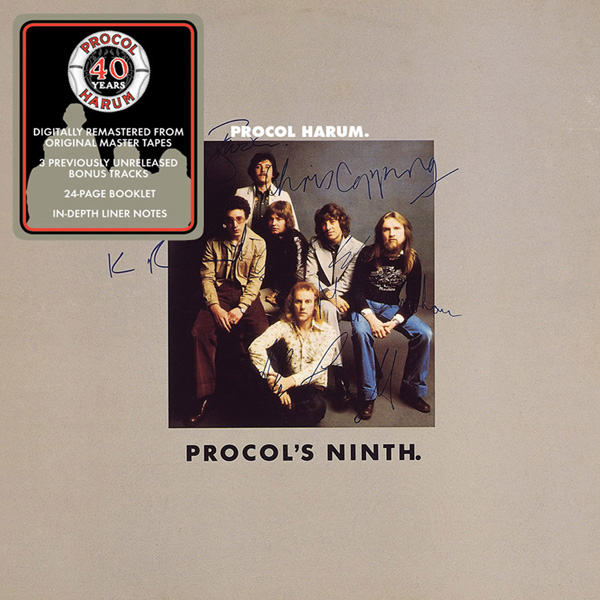

Procol Harum had felt ‘in a bit of a rut’ following a run of five albums with producer Chris Thomas (his predecessors, Denny Cordell and Matthew Fisher, had presided over two and one respectively). Wordsmith Keith Reid wanted ‘to break the cycle of going into the same studio, at the same time of year’. Procol migrated from AIR in Oxford Street to Ramport Studios in Battersea (a facility built by The Who), and put themselves in the hands of new, American producers. The posed portrait (taken in London’s Chinatown by fashion-photographer Terence Donovan’s then assistant James Cotier, who shared Procol’s Southend origins) was part of this clean sweep.

‘Yes, it was a big deal for us to be

pictured on the cover like that,’ Keith told me. By appearing ‘as themselves’ –

previous sleeves had shown the band cartoonised (Home), posterised (Broken

Barricades), painted (the Live album), and depersonalised by

formal dress (Grand Hotel) – the members of Procol Harum

were forsaking their habitual reticence. Their printed signatures further

brought them into focus as individuals (and these autographs, paradoxically both

authentic and fake, would flummox a later generation of eBay traders, hawking

‘this unique item’ for sale).

‘Yes, it was a big deal for us to be

pictured on the cover like that,’ Keith told me. By appearing ‘as themselves’ –

previous sleeves had shown the band cartoonised (Home), posterised (Broken

Barricades), painted (the Live album), and depersonalised by

formal dress (Grand Hotel) – the members of Procol Harum

were forsaking their habitual reticence. Their printed signatures further

brought them into focus as individuals (and these autographs, paradoxically both

authentic and fake, would flummox a later generation of eBay traders, hawking

‘this unique item’ for sale).

Each instrumentalist was also sharply revealed in sonic terms, thanks to the fresh approach of incoming producers Jerry Leiber & Mike Stoller. This legendary duo’s impact on popular music is too extensive to chronicle here; but as well as Hound Dog and Jailhouse Rock they wrote a couple of dozen Coasters’ hits, including Poison Ivy, with which pianist/vocalist Gary Brooker first graced the UK charts fronting his former group, The Paramounts. Leiber & Stoller enjoyed a parallel career as producers, and caught Brooker’s ear again in 1972 with their work on the Dylanesque Stealers Wheel hit, Stuck in the Middle with You. It was a very significant moment for Brooker, Reid and co when, three years later, such senior figures agreed to work with Procol Harum.

Praising Procol’s Ninth in Sounds (‘in every way an excellent record’) Angus MacKinnon welcomed the way Leiber & Stoller’s ‘stark and viciously exact’ sound replaced Chris Thomas’s expansive ‘sound-wall’ proclivities. (Phil Spector links these opposing approaches: the guitarist on several Leiber/Stoller hits, he produced George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass, on which Chris Thomas played during his Abbey Road apprenticeship). MacKinnon also adjudged Ninth ‘affectionately retrospective’, perhaps because it featured two non-originals, covers of Leiber/Stoller themselves and Lennon/McCartney, in apparent homage to giants of pop history.

This connection with powerful musical figures from the past perhaps influenced the album’s ‘jokey title’ as Keith puts it now. Procol’s Ninth was not just a literal description, but seemingly placed the band alongside Beethoven, Bruckner, DvořŠk, Schubert, Vaughan Williams and other composers whose symphonic output had peaked at that number. (Like Exotic Birds, the chosen title also avoided highlighting any particular song, lest the remainder seem like filler). Prominent American critic Bud Scoppa (Rolling Stone, 9 October 1975) commented on the title’s ‘symphonic allusion’, but overlooked its self-deprecating subtext: DvořŠk and co. not only peaked with their ninth symphonies, they didn’t complete any more! With two non-original songs among a collection that mentioned writer’s block, was this an ominous clue from the celebrated Brooker/Reid songwriting team?

Though Sounds felt that ‘Ninth signals reinvigoration for Procol Harum,’ Pandora’s Box had been written in 1967, like the band’s other big hits. Released in July 1975 (a month before the parent album) this sprightly revival sounded quite unlike its co-evals A Whiter Shade of Pale, Homburg, and Conquistador. Yet Brooker’s voice remained distinctive. ‘The day we mixed it I had it on a cassette in a taxi,’ Gary told me, ‘and played it to the driver, who didn’t recognise me. Who do you think that is? Procol Harum, he replied.’

Devotees of Procol’s five-piece sound

wondered why the new producers had ceded the stand-out instrumental break to an

anonymous New York session flautist; but Leiber & Stoller’s hitman ears (maybe

recalling the catchy woodwinds in Nina Rossi’s Untrue Unfaithful hit from

1965, a melodic cousin of the Procol tune?) were vindicated. Though Melody

Maker (2 August 1975) sourly predicted a miss (‘One to play when you’re

watching a telly programme and the sound has been turned down’), UK

record-buyers took Pandora’s Box to a convincing No 16: it had several

live TV airings and has been a stage favourite ever since.

Procol had resurrected early songs before: Monsieur R Monde, on 1974’s

Exotic Birds and Fruit, had been attempted in a session seven years before

Chris Thomas re-recorded it in reverberant, Spectoresque style. Leiber & Stoller

brought Pandora to life using a varied sound-palette: Brooker’s marimba

and high string synthesisers, Mick Grabham’s strummed acoustic guitar, flanged

lead sound and synth-like sustain. Its delicacy contrasted the strongest

Exotic Birds chart contender, Nothing But the Truth, which Brooker

had found ‘a bit noisy … loud from start to finish’. Pandora’s Box has

mutated more than any Procol offering. When first recorded (25 July 1967) its

core was a slow four-note guitar drone adapted from Ravi Shankar; in 1973 it

became a countrified live number, with chugging back-beat and copious BJ

cowbell; after the Procol’s Ninth single (‘Gothic calypso’, according to

Chrysalis’s press-pack) it became an instrumental on The Symphonic Music of

Procol Harum (1995), featuring James Galway: thus the alien flute eventually

pervaded the entire song, silencing Keith Reid’s extravagantly motley libretto.

My Own Choice, Reid’s 2000 Charnel House anthology, includes Pandora’s Box: yet there Cock Robin’s ‘favourite drink’ is no longer ‘the Persian that’s as warm as mink’ but ‘the chocolate …’ . Such arbitrariness hallmarked Keith’s early style, but lyrics from the Procol’s Ninth period are much more tautly-constructed. About Fool’s Gold he told me ‘I’m always looking for the right image to suggest something lurking around the corner.’ Brooker’s clear diction, and the appropriately sparse, muscular arrangement, showcase lines in which every image earns its place, bristling with fruitful ambiguity: ‘monsters’ and ‘pledge’ together might relate to the tribulations of an alcoholic, yet ‘pledge’ and ‘hollow ring’ resonate with matrimonial overtones.

It was puzzling, in light of such emotive work, that Rolling Stone criticised Reid’s rootedness in an approach ‘that ignores meaning and feeling’, even alleging his ‘resolute redundancy’! Over thirty years on, Bud Scoppa – who greatly admired Procol ‘at its early peak’ – explained himself, telling me that the band had ‘always depended on the algebra of the visceral (Trower, fantastic drummer BJ Wilson) … and the intellectual (Fisher’s baroque organ, Reid’s Coleridge-like lyrics)’. Reid was ‘exposed as a lyricist in the visceral/intellectual imbalance,’ he felt, because ‘Trower had never been viably replaced.’ Despite this nostalgic outlook, Scoppa’s Rolling Stone review did praise guitarist Mick Grabham’s ‘exceptional performances’, and the newfound ‘spirit and looseness’ of Procol’s Ninth in general.

The ‘raw’ Fool’s Gold track lacks Mick’s fine solo; it’s a live studio performance that Procol later enhanced, replacing some drums and piano, and Brooker’s guide vocal. Leiber & Stoller added brass arrangements, recorded in New York sessions under Gary’s supervision. The finished product ends with some tasty new piano, a characteristic glimpse of melodic interest as the music sinks below earshot.

In its ‘raw’ version Taking the Time opens with a Brooker piano prelude, free and bluesy until the elaborated Bach-like cadence in bar twelve. This tuneful, haunting piece is ‘very rhythmic and seductively understated’ in the words of Sounds, and swings with the assurance of players sharing long experience: it was Brooker and Wilson’s ninth album together, Chris Copping’s fifth, Alan Cartwright’s fourth and Mick Grabham’s third. Was Rolling Stone right that the producers’ ‘only obvious error is their use of overdubbed horns for coloration in places where Chris Copping’s organ would have been more contextually apt’? For the first time, we have organ and horn versions to compare. Reid’s lyric, with its sophisticated wordplay, was also anthologised in My Own Choice. Though certain phrases (especially ‘taking notes and stealing quotes’) clearly pertain to the writer’s craft, the procrastinating protagonist is not Reid himself: Keith was apparently thinking of Van Gogh, ‘living in the country’. How, though, does ‘act the hero’s part’ relate to the Salty Dog album cover, where the ‘Hero’ sailor is Reid himself, as portrayed by Dickinson, his then girlfriend?

The ‘raw’ Unquiet Zone has already seen some overdubbing: two keyboardists contribute the piano, organ and Hohner D6 clavinet tracks, at once gritty and exceptionally clean. BJ Wilson’s intricate, driving drums – comparably foregrounded only in the laborious multi-tracked solo on 1971’s Power Failure – are already stereo-panned in places. Leiber & Stoller have yet to splice in a different ending, saving 45 seconds, and of course re-record Gary’s amusing, disappearing vocal. They’ll also add punchy and exciting brass players (David Sanborn among them), and lose some Hammond (‘Chris Copping’s appearances astride his organ are too seldom’ as Tony Stewart strangely put it in New Musical Express 16 August 1975).

Reid borrowed The Unquiet Zone’s title from a TV documentary about World War I; ‘bitter strife’ also occurs in Fool’s Gold. Brooker’s finished vocal invests the text with great passion: it’s hard to imagine another vocalist bringing such conviction to ‘an awful waste of guts and gore’. Leiber & Stoller neatly match the shell-scream of Gary’s voice – both pitch and timbre – to the opening of Grabham’s mighty solo. The keyboards’ chordal offbeats supply some tonal mischief and the sliding-semitone harmonies – jazzy chords preceding the vocal entry for instance – foreshadow parts of The Worm and the Tree on Procol’s follow-up, Something Magic: it was probably brewing in Brooker’s mind and hands at this time. The Unquiet Zone could extend to twelve minutes in concert (at Mannheim, 4 February 1977, BJ’s solo was a good seven minutes). So how did such an exhilarating band turn in the track that follows?

The Final Thrust – with its simple hook and ‘facetious tango tempo’ (the Chrysalis Press kit again) – brings Side One of Procol’s Ninth to a somewhat anaemic conclusion. The heavy double-tracked piano, the thin Hammond, and the dogged almost-comic backing voices make a rather colourless ensemble, though Brooker’s solo break and Alan Cartwright’s prominent bass runs are pleasing. BJ’s military-sounding snare, revealing his Boys’ Brigade heritage, invites us to construe the brief lyric in terms of warfare (Keith’s handwriting annotates Gary’s file-copy ‘One for the troops’). The Final Thrust seems to have stumped Leiber & Stoller, yet Angus MacKinnon in Sounds numbered it among the album’s three ‘most resilient’ tracks, NME’s Tony Stewart called it ‘my own favourite’, and Chrysalis put out a 45 rpm edit (losing 75 seconds) as ‘the follow-up to their smash hit Pandora’s Box.’ NME considered this ‘classic B-side material, ie half-hearted’: yet flipping it – promoting Taking the Time to the A-side – would scarcely have armed Procol to compete with Queen’s latest (Bohemian Rhapsody!) or their own Homburg, inconveniently re-released on Cube.

Procol Harum did have hopes for Without a Doubt (originally The Poet) as a single. As early as October 1974 Brooker forewarned a Bradford audience of its being ‘in stores and jukeboxes soon’. The band had played a self-produced version (recorded at Phillips Studios) to Canadian producer Bob Ezrin, who’d used BJ on Lou Reed’s 1973 Berlin album, which Procol rated highly. But Ezrin was looking for ‘that dance pocket’, as Grabham recalls, while by Copping’s admission their Phillips track was ‘ploddy’. So Procol Harum finally recorded The Poet with Leiber & Stoller, who sadly didn’t wring a hit from its somewhat ponderous potential. The song had elements of a Procol masterpiece, and its chorus – the ascending bass-line and ear-catching chord-inversions – remains a high point in Brooker’s writing. Reid’s text is also strong: its rich wordplay depicts a rock-lyricist’s fantasy about breaking into mainstream literature, the genre evidently immaterial! His breezily optimistic verses chillingly alternate with increasingly-anxious choruses; small wonder it features in My Own Choice.

Mick feels that the Procol’s Ninth producers ‘generally concentrated more on the structure of the songs’, leaving the sounds to engineer John Jansen. The Poet demo had its own monolithic structure and – beyond taming BJ’s long, wayward fills between verses – Leiber & Stoller found little to do bar some sonic tinkering. The Chrysalis press-kit alludes to ‘the poet’s delusions of grandeur’; and the song’s grandeur does rather suffer at the producers’ hands. Gary’s BŲsendorfer piano sounds superb, and the band sets out majestically, but the stately sound is intercut with a contrasting treatment after just 48 seconds: echoey voice, tambourine, and a whimsical reggae off-beat. When the brass comes in, sounding suitably imposing, this disparity becomes even more incongruous (‘What were we, Chicago?’ was Mick Grabham’s wry comment). Leiber & Stoller’s methods pleased some critics – Crawdaddy (October 1975) spoke of ‘a cathartic spring breeze for Procol’ – but touring versions of the song reverted to its original, homogeneous texture.

The Piper’s Tune (Pandora’s B-side in the UK) uses a Lowrey organ to invoke the Highland Pipes; the Caledonian sound-world is enhanced by droning, sustained accompaniment and Brooker’s intermittent Scots accent. Reid’s vengeful words hark back to the familial dysfunction of 1971’s Simple Sister (in which sweets were also withheld); his punchline, ‘The piper, he calls the tune’, stands the established proverb on its head. Brooker’s ambitious melody roams from key to key, stretching his tenor almost to Whiter Shade of Pale heights. Leiber & Stoller seem content to leave the band’s careful ensemble-playing unadorned (except by an enigmatic sotto-voce ‘hi’, deep in the mix around 2.30): in concert performance the song exuded much more drama. To Procol’s disquiet their producers didn’t work rock-and-roll hours, preferring to clock off in the early evening: yet this track (which NME found ‘lethargic’) sounds like something recorded at the lowest ebb of the night. Nonetheless Detroit’s influential CREEM (November 1975), which surprisingly dismissed Side One as ‘largely formulaic and monotonous’, found Side Two’s Brooker/Reid originals ‘as strong a musical block as anything in the group’s last five years’.

The final Brooker/Reid tune really is an energetic gem. Typewriter Torment was part of the ‘killer set’ (Roy Carr in NME) with which Procol marked the closure of London’s Rainbow Theatre in March 1975: it still sounds good onstage thirty years later, albeit without the demented cowbell of BJ Wilson, who died in October 1990. Torment gets good vigorous mileage (like 1967’s Kaleidoscope) from artful deployment of some simple chords; oddly, in view of the fret-friendly key, Copping’s typically serpentine organ gets the solo spotlight. Leiber & Stoller’s detailed, integrated production – oohs and aahs, hand-claps, drum-phasing, fat guitar, extra beats, false starts, and final-verse congas – makes other tracks on the album sound underdeveloped. Heightened language, both medical and technical, and abundant wordplay convey a literary addiction: few rock numbers namecheck Roget’s Thesaurus! Keith Reid told ZigZag in 1977 that his songs about the writing process had been over-interpreted: he wasn’t ‘getting paranoid about it all’. My Own Choice, set almost wholly in Palatino, playfully monospaces this song in Courier, the typewriter font.

Though

Typewriter Torment’s ‘I’ve done with it all,’ tempt listeners to interpret

the album’s two cover-versions as evidence that the Procol creative team was

running dry, Keith assures me he experienced writer’s block only before 1970’s

Home album. In fact Procol did enjoy the surprise value of playing

occasional covers in concert, even mixing Get Back into The Unquiet

Zone during some Ninth promotional shows. Gary (who had played the

final Beatles tour with The Paramounts, and who later guested on Paul, George

and Ringo solo-albums) would teasingly introduce ‘a big Sixties hit’, when the

crowd called out for A Whiter Shade of Pale … then launch into Eight

Days a Week. This Lennon/McCartney number, tepidly executed in the studio

‘for a laugh’, was captured by Leiber & Stoller, and reputedly railroaded on to

the album.

Procol tell how their producers also tried to tempt them with recent songs of

their own, rejected by Peggy Lee from what became her Mirrors album. (One

was a satirical tango in praise of Humphrey Bogart: Procol’s subsequent live

Grand Hotel performances included a burst of Hernando’s Hideaway,

over which Brooker improvised his own paean to Bogie: it wasn’t Leiber &

Stoller’s lyric, but one must suspect an influence). Instead Procol recorded

60s’ classic I Keep Forgetting (later also covered by David Bowie),

representing the classic Leiber/Stoller of their youth. Peter Stoller, the

co-composer’s son, told me he considered Procol’s ‘one of the best remakes, if

not the best, emphasising the soulful aspects of the song rather than

riffing on the esoteric arrangement of Chuck Jackson’s original record’.

Had these covers been surfacing now, as bonus tracks, they would seem fascinating; yet such straightforwardly love-oriented songs (perhaps heralding more sentimental lyrics like 1991’s One More Time) felt somehow out of place on a 70s’ Procol album. And out-of-house contributions occupied space that fresh Brooker/Reid compositions could have filled more interestingly: Chris Copping himself wishes So Far Behind (unrecorded until the 2003 album) had closed Procol’s Ninth: ‘the album might have been meatier’.

In conclusion, then, while Procol Harum did escape the ‘bit of a rut’ they’d been labouring in, their pairing with Leiber & Stoller was not a perfect one: Procol’s Ninth, while its highs outweigh its lows, is not an unqualified ‘Ode to Joy’. Yet time would show that Procol had three further studio albums in them and, at the time of writing (September 2009), they are recording again: excellent news for fans of such enigmatic, individual music.

Roland Clare © 2009