Procol HarumBeyond

|

|

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |

|

Anthony Rowat writes to BtP

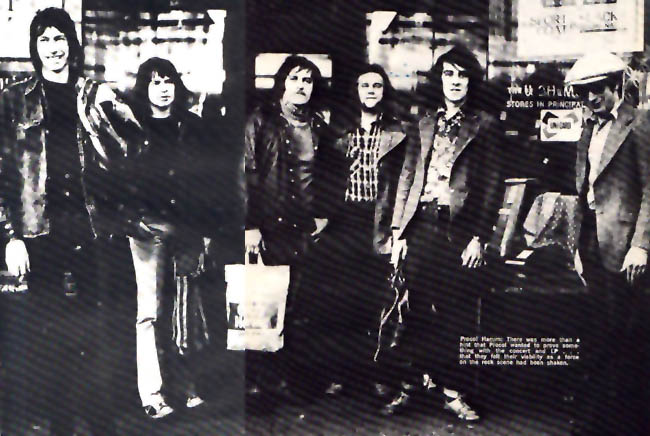

The Circus magazine article is from July 1972 and has, I

think some terrific pictures of the band: in the large picture BJ

looks like a street urchin, Dave looks charismatic, Chris looks

lost and Keith looks like a cross between Groucho Marx and Woody

Allen. The small picture is also very nice (more Groucho Keith);

and the picture of Dave and Barrie is one of the sweetest

pictures of BJ ever, I think. The article itself is also very

nice.

A Nervous Night With Procol Harum: Behind

The Scenes of Procol Live

The critics agree that Procol Harum Live

soars to a heady triumph. But as they prepared to record in

Edmonton's Jubilee Auditorium, Procol seemed close to sinking in

defeat.

|

Procol Harum: There was more than a hint that Procol wanted to prove something with the concert and LP ... that they felt their viability as a force on the rock scene had been shaken |

The small green cassette tape recorder nestled inconspicuously on my lap, tenth row center in Edmonton's Jubilee Auditorium - not inconspicuously enough though. A gentleman in a blue suit loomed over my shoulder, "I'm sorry, sir, but you can't record in here." Seventy feet away in the auditorium lounge Wally Heider, his large bulk perched on a small white stool, hunched over the control board of what is probably the most sophisticated portable recording apparatus in the world, six feet of the most advanced in electronic technology valued at over $100,000. Looming over Heider's shoulder? Three technicians from Canada's national television network; a member of Procol Harum, England's critically acclaimed, if not always best selling rock band; and the general manager of the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra.

Wally Heider has permission, nay blessing, to record in the auditorium. And why not? Heider's recording of the Procol Harum Edmonton symphony concert is destined to be released as a record on the A & M label. Procol Harum Live with the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra, the third ever such recording made with a rock band and full orchestra and the first ever recorded on a 16 track machine.

Longhairs storm the fortress of posh: It is the first time an English group has ever been allowed to record with a North American orchestra in North America, and it is the first time the Edmonton Symphony has ever been captured on tape. No small stir is caused in the local media by the news that such a venture is happening in Edmonton - a city of 500,000 in Northern Alberta, where they still talk about the day Jethro Tull came to town. Edmonton is not on the beaten track of rock and roll. Only one hall in the city will suffice for the concert - the 2,700 person capacity Jubilee Auditorium, a brick and marble structure more suited to an operatic production than Procol Harum. The seats are red plush, and the manager is reluctant to allow folk acts to perform there, let alone a rock band.

Wally Heider peers into the closed circuit TV screen hooked up just for the occasion. Through it he sees Procol Harum and the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra rehearsing on the auditorium stage. It is the last rehearsal for the performance. Heider is having problems with one of the connections between the mikes onstage and his control panel. The cellos are coming through on a track that is supposed to be picking up the violins. Onstage, Procol drummer BJ Wilson complains that the Symphony is inaudible through the speakers which have been placed onstage for the purpose. A pre-recorded explosion, an integral part of one of the songs, fails to appear on cue. It is, all things considered, a nervous afternoon.

Thorns in the path: The concert has been sold out for twelve days in advance, resulting in an abortive attempt the same afternoon to arrange a second concert after midnight. A woman in the Symphony reports that she is unable to acquire a ticket even for her son. Scalpers are charging between $20 and $30 a ticket.

Communications between the group and the orchestra are not easy. Procol Harum talks in terms of solos and sequences. The Symphony knows bars and lettered reference points on their sheet music, necessitating that the orchestra's conductor translate between the two. In addition to problems stemming from matters musical, there is a strictly physical difficulty. Procol Harum is strung across the front of the auditorium stage, their backs to the orchestra and to the tuxedoed conductor. For four members of the group, only a turn of the head is necessary to catch the conductor's cues. Drummer B.J. Wilson, however, sitting with the podium directly behind him, has no such recourse, as a few strained neck muscles show. In a last minute inspiration just before the end of the final rehearsal, someone brings a large truck rear view mirror onstage. The mirror is taped to one of BJ's cymbal stands, focussed on the conductor's baton, and visual contact is established.

|

BJ Wilson, drums: BJ's problem is solved when someone tapes a large truck rear view mirror to one of his cymbal stands |

Unwinding a union knot: Suddenly a storm in a tea cup brews up between Procol and the orchestra's representative of the Musicians' Union. The Union representative at first demands that the recording machine not be used until the actual concert, making it impossible for the engineers to set their sound level. Procol and the engineers make their point, and the machines are turned on for rehearsal; but the Union man continues his harassment. He sits through rehearsal with a stopwatch and when time is up pulls the orchestra off the stage ... in the middle of a song. Guitarist David Ball, however, eases the tension somewhat by striking up a first name friendship with ESO concert master, Charles Dobias. The compact, sartorially perfect Dobias and the lanky Ball make an incongruous pair, joking as they leave the stage.

Paper cups in Tuxedo Palace: All things considered, the

nervousness is understandable, as is the apprehension of the

Jubilee management at the storming of their establishment by an

entourage of the long-haired young - and not so young - essential

to any rock performance. Smoking onstage and drinking wine from

paper cups, their conduct poses a cheerful challenge to the

traditionally staid auditorium. Anticipation of the performance

and the prospect that the recording made this night could become

a best-selling pop album infects the Auditorium, despite the

disquieting amount of wire and sound equipment arranged around it.

The anticipation has been building for several months now. The

concert was born in a chance comment made to Symphony Assistant

General Manager Bob Hunka by Toronto rock columnist Ritchie Yorke

at an Edmonton rock competition seven months before. Hunka,

looking to follow up to the enormously successful Lighthouse-Symphony

collaboration, asked Yorke for advice. "Procol Harum,"

suggested Yorke, who then supplied Hunka with details of a

previous symphony performance Procol had staged, plus an address

where the group might be reached and all the resources of his

post as dean of Canadian rock critics.

Plastering cracks in the group: Procol welcomed the

proposition. They had planned to come to North America to record

an album anyway and were taken by the suggestion that the album

be recorded at the proposed concert. There was more than a hint

in Procol's acceptance that they wished to prove something with

the concert - that their viability as a force on the rock scene

had been altered by personnel changes they had recently undergone.

Robin Trower, their guitarist, left the band some months before

to lead his own group; and replacement David Ball was found

through an ad in the English trade magazines. Mathew [sic] Fisher, organist, had also left, as

had bassist David Knight [sic],

making way for Chris Copping who at first doubled on organ and

bass, then stuck strictly to organs when Alan Cartwright moved

onto the scene. In many ways, the changes were reminiscent of the

turmoil in the band at their beginning in 1967. In those days,

Procol was no more than pianist Gary Brooker and lyricist Keith

Reid - a songwriting team who, with the help of a few studio

musicians, [sic] recorded the

classic "Whiter Shade of Pale." Trower, BJ Wilson and

Knight [sic , sic] were added for

the recording of their first album Procol Harum (on the Deram

label). Of these three original Harumites, only Wilson now

remains.

A nervous gamble: Now, Procol was determined to prove that their strength had survived the latest upheaval. "It's going to be good," said B.J. at the close of the last rehearsal. Then, scratching his head with grim determination, "It had better be good." Success was no mere artistic necessity. To break even financially on the concert, Procol has to sell over 150,000 albums. Though ticket sales covered the group's transportation fees and the $2000 hotel bill run up during the band's stay at Edmonton's Holiday Inn, in order to pay the staggering rates demanded by Heider's recording unit and the Edmonton Philharmonic yet still come up with a profit, Procol is going to have to sell more copies of this LP than of any record it's ever put out before. With this in mind, the concert opens on a nervous note.

BJ Wilson's drums on "Conquistador" are unusually heavy-handed, and David Ball, with an over extended solo, destroys an orchestra entry, but the crowd pays no mind. The capacity audience of Edmonton's richest hip is on Procol's side and determined to make the band feel at home An unforgettable collective guffaw escapes their lips when the 24-voice da Camera chorus, who accompanied the orchestra, rises for the beginning of "Whaling Stories," gives one loud introductory yell, then quickly sits down again; and Gary Brooker draws an apprehensive chuckle for breaking down in mid-song and confessing quite honestly that it is all messed up.

Courage from the voice of doom: Not until Procol launches into In Held 'Twas In I do the orchestra and the band sound comfortable together. Layer upon layer of instruments in octaves pile one upon another building the tension to a screaming climax. Doom-inspiring bass and guitar figures follow. Then a slight, stooping figure in wire-rimmed glasses and tweed coat, apprehensively clutching a sheaf of papers, appears by a microphone on the left hand side of the stage, and his voice thunders out softly over the sound of the instruments:

In the darkness of the night

Only occasionally relieved by glimpses of Nirvana

As seen through other people's windows

Wallowing in a morass of self despair

Made only more painful by the knowledge

That all I have [sic] is of my own

making

When everything around me, even the kitchen ceiling

Is [sic] collapsed and crumbled

without warning

And I am left standing ...

Looking up and wondering why and wherefore ...

It is Keith Reid, [sic … unless this was an unrecorded take] Procol's retiring lyricist, unexpectedly making second-ever stage appearance to read an excerpt from the cantata that might be the work's rationale.

If I can communicate

If [sic] in the telling and the

baring of my soul

Anything is gained

Even though the words which I use are pretentious

And make me [sic] cringe with

embarrassment

|

Gary Brooker, piano and vocals: An uneasy chuckle ripples through the audience as Gary breaks down in mid-song |

Then the words veer strangely from tortured confusion into the nearly humorous tale of the pilgrim who spends five long years in contemplation waiting to ask the Dalai Lama the ultimate question - the question of the meaning of life - only to be granted an audience in which the Dalai Lama smilingly announces, "Well, my son, life is like a beanstalk, isn't it?"

The last tough step to triumph: The standing ovation stretches into minutes and Procol announces that they will re-perform several of the songs - as much for the benefit of the 16-track recorder as for the enthused audience, but the audience stays with them. They repeat "Conquistador," the second attempt joyously refuting the uncertainty of the first; and the program ends in open triumph.

The flamboyant BJ Wilson, the methodical bassist Alan Carter [sic], the alert David Ball, cossack-mustached Gary Brooker and youthful Chris Copping wear wide grins. For the da Camera chorus, Derek Sutton, Procol's manager, has only praise; but of the symphony he is more critical. Careful listening to the tapes after the concert reveals that the ESO drummer was persistently out of time. It is necessary to mix him down and sometimes eliminate him completely during the final stages of production. "Not a bad orchestra," was Derek's final verdict. "Hardly up to the calibre of the London Philharmonic," but definitely "not a bad orchestra."

Thanks, Marvin (t. torment) and Anthony (scans)

Many more pages devoted to the Edmonton concert

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |