Before

and after: the Paramounts (below left) became Procol Harum (below right).

Before

and after: the Paramounts (below left) became Procol Harum (below right).

Procol HarumBeyond

|

|

|

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |

|

Classic rock that captured the mood of 1967

Procol Harum will be remembered for their chart-topping A Whiter Shade Of

Pale, if nothing else. Hitting the Number 1 slot in the UK in May 1967, and

Number 5 in the US in July, it was a dreamy, fantasy-laden sound which drifted

easily into the atmosphere which pervaded the summer of 1967. It hogged the

Number 1 position for six weeks and even in 1972, when it was re-released, it

climbed to Number 13 in the UK.

But behind the one-hit-wonder label, the history of the band with the strange, exotic name spanned almost twenty years and encompassed a wide progression of musical styles. They had their beginnings at the time of the beat and R&B booms, reached their chart zenith in the height of flower power in the Summer of Love, and worked as one of the main bands on the American tour circuit in the Seventies. The history is a chequered one and the line-up changed constantly, the stable core of Gary Brooker and lyricist Keith Reid ensuring a certain continuity of style despite changing trends.

The story begins with the Paramounts, a Southend R&B group that was formed in 1960, when a schoolboy band called the Raiders was re-christened by a local dance hall manager. The line-up at the time revolved around pianist Gary Brooker (born 29 May 1945) and guitarist Robin Trower (born 9 March 1945) and included drummer BJ Wilson (born 18 March 1947) and bassist Chris Copping (born 29 August 1945). Their sporadic public appearances were split between playing dates on their own, doing cover versions of American rock’n’roll and Shadows instrumentals, and backing solo artists visiting the Southend area.

Gary Brooker recalls the period thus: ‘We backed Tommy Bruce on a thing called ‘Rock Across The Channel’ on the boat to Calais. It was us, Gerry and the Pacemakers, Duffy Power, the Dreamers and the Shadows … they would turn up five minutes before they were due to go on for their 20-minute sets. They would bring charts, with the chords scribbled down, so anybody who could follow a chord chart used to get the job of backing them.’

By 1963, the group had settled down with a personnel of Brooker, Trower, Wilson and bassist Diz Derrick. In that year, soon after leaving school, they got a recording contract with Parlophone, who were busy signing up provincial groups in the wake of the Beatles. The Paramounts’ first effort for the label was a version of Poison Ivy, the old Coasters hit from 1959, which sneaked into the Top Fifty in January 1964. It was to be the high-point of the Paramounts’ career, however. Despite constant touring, TV appearances on shows like Ready Steady Go! and Thank Your Lucky Stars, and the accolade of being dubbed ‘the best R&B group in England’ by the Rolling Stones, they got nowhere. Five further singles for Parlophone flopped – including Bad Blood, which was banned when the BBC decided it was about syphilis – and by 1966 they were once more reduced to backing other artists – first Beryl Marsden on the Beatles’ final British tour, then with Sandie Shaw in Paris, and finally behind Chris Yesterday Man Andrews in Germany. Robin Trower refused to go on this last expedition, and when they returned home, the Paramounts called it a day.

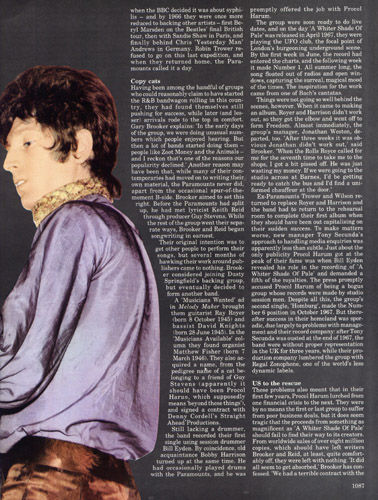

Before

and after: the Paramounts (below left) became Procol Harum (below right).

Before

and after: the Paramounts (below left) became Procol Harum (below right).

Copy cats

Having been among the handful of groups who could reasonably claim to have

started the R&B bandwagon rolling in this country, they had found themselves

still pushing for success, while later (and lesser) arrivals rode to the top in

comfort. Gary Brooker explains: ‘In the early days of the group, we were doing

unusual numbers which people enjoyed hearing. But then a lot of bands started

doing them – people like Zoot Money and the Animals – and I reckon that’s

one of the reasons our popularity declined.’ Another reason may have been

that, while many of their contemporaries had moved on to writing their own

material, the Paramounts never did, apart from the occasional spur-of-the-moment

B-side. Brooker aimed to set this right. Before the Paramounts had split up, he

had met lyricist Keith Reid through producer Guy

Stevens. While the rest of the group went their separate ways, Brooker and

Reid began songwriting in earnest.

Their original intention was to get other people to perform their songs, but several months of hawking their work around publishers came to nothing. Brooker considered joining Dusty Springfield’s backing group, but eventually decided to form another band.

A ‘Musicians Wanted’ ad in Melody Maker brought them guitarist Ray Royer (born 8 October 1945) and bassist David Knights (born 28 June 1945). In the ‘Musicians Available’ column they found organist Matthew Fisher (born 7 March 1946). They also acquired a name, from the pedigree name of a cat belonging to a friend of Guy Stevens (apparently it should have been Procol Harun, which supposedly means ‘beyond these things’), and signed a contract with Denny Cordell’s Straight Ahead Productions.

Still lacking a drummer, the band recorded their first single using session drummer Bill Eyden. By coincidence, old acquaintance Bobby Harrison turned up at the same time. He had occasionally played drums with the Paramounts, and he was promptly offered the job with Procol Harum.

The group were soon ready to do live dates, and on the day A Whiter Shade

of Pale was released in April 1967, they were playing the UFO club, the

focal point of London’s burgeoning underground scene. By the first week in

June, the record had entered the charts, and the following week it made Number

1. All summer long, the song floated out of radios and open windows, capturing

the surreal, magical mood of the times. The inspiration for the work came from

one of Bach’s cantatas.

Robin Trower (right [sic]) later went solo.

Things were not going so well behind the scenes, however. When it came to making an album, Royer and Harrison didn’t work out, so they got the elbow and went off to form Freedom. Almost immediately, the group’s manager, Jonathan Weston, departed, too. ‘After three weeks it was obvious Jonathan didn’t work out,’ said Brooker. ‘When the Rolls Royce called for me for the seventh time to take me to the shops, I got a bit pissed off. He was just wasting my money. If we were going to the studio across at Barnes, I’d be getting ready to catch the bus and I’d find a uniformed chauffeur at the door.’

Ex-Paramounts Trower and Wilson returned to replace Royer and Harrison and the band had to return to the rehearsal room to complete their first album when they should have been out capitalizing on their sudden success. To make matters worse, new manager Tony Secunda’s approach to handling media enquiries was apparently less than subtle. Just about the only publicity Procol Harum got at the peak of their fame was when Bill Eyden revealed his role in the recording of A Whiter Shade of Pale and demanded a fifth of the royalties. The press promptly accused Procol Harum of being a bogus group whose records were made by studio session men. Despite all this, the group’s second single, Homburg, made the Number 6 position in October 1967. But thereafter success in their homeland was sporadic, due largely to problems with management and their record company: after Tony Secunda was ousted at the end of 1967, the band were without proper representation in the UK for three years, while their production company lumbered the group with Regal Zonophone, one of the world’s less dynamic labels.

US to the rescue

These problems also meant that in their first few years, Procol Harum lurched

from one financial crisis to the next. They were by no means the first or last

group to suffer from poor business deals, but it does seem tragic that the

proceeds from something as magnificent as A Whiter Shade of Pale should

fail to find their way to its creators. From worldwide sales of over eight

million copies, which should have left writers Brooker and Reid, at least, quite

comfortably off, they were left with nothing. ‘It did all seem to get

absorbed,’ Brooker has confessed. ‘We had a terrible contract with the

production company, and it always cost a lot of money to get rid of all these

managers and other people. In fact, we did a tour of the States and all the

money went to people we’d never signed a contract with.’

Right:

Procol Harum in a later incarnation, with BJ Wilson on drums, Alan Cartwright on

bass and Mick Grabham on guitar

Right:

Procol Harum in a later incarnation, with BJ Wilson on drums, Alan Cartwright on

bass and Mick Grabham on guitar

What saved Procol Harum from going the same way as the Paramounts was the US. A Whiter Shade of Pale’ had been a huge (Number 5) hit there, as it was all round the world, but the Americans seemed keen to hear what else the band were doing, and were given plenty of opportunity to do so, since Procol Harum toured there eleven times in under four years! That work rate, allied to a rather more efficient record company in A&M, kept the group well to the fore across the Atlantic, during three or four years when they were all but forgotten at home. They also worked regularly in Europe, where they had considerable success, and it wasn’t until early 1972 – after they had switched to the fast-growing Chrysalis label – that they did their first proper tour of the UK as support to Jethro Tull.

In what little time remained between these travels, the band made three albums. The 1967 début, Procol Harum (a restrained title for such over-the-top times) was hastily and rather poorly produced by Denny Cordell, but not bad for all that. It was a sombre, stately work with a classical dignity, the despair of Reid’s cryptic lyrics set in contrast to the deliberate architecture of the music, the religiosity of Fisher’s organ-playing and Brooker’s gospel-tinged piano and vocals.

Cordell did little better with Shine On Brightly, recorded through late 1967 and early 1968, though what emerged was arguably a greatly under-rated album. At this point Cordell got side-tracked by Joe Cocker, and Matthew Fisher took over for A Salty Dog (1969).

Having been bitten by the production bug, Fisher left to concentrate on that and to make a couple of solo albums during the Seventies. David Knights also departed to take up management – he probably decided that’s where the money was – and both were replaced by Chris Copping. Chris had left the Paramounts to go to college, where he had learned to play the organ, as well as bass. With Fisher gone, Chris Thomas was called on to produce their fourth album, Home, and this proved to be the start of a fruitful combination which lasted for four years and five albums.

Lyricist

Keith Reid (above) and composer Gary Brooker (inset [above]) remained the

mainstay of the band, while Chris Copping (inset right) switched from bass to

organ and back.

Lyricist

Keith Reid (above) and composer Gary Brooker (inset [above]) remained the

mainstay of the band, while Chris Copping (inset right) switched from bass to

organ and back.

The group personnel was rather less consistent. Robin Trower left, after discovering a songwriting talent during the making of the album Broken Barricades, and formed a sub-Hendrix trio which has done noticeably better commercially than Procol Harum. He was replaced briefly by Dave Ball, and then more permanently by Mick Grabham, who had previously been with Cochise. Chris Copping eventually concentrated on organ when Alan Cartwright came in, from Brian Davison’s Every Which Way, on bass. When Cartwright left in 1976, Copping moved back to the bass and Pete Solley – previously a member of Snafu with original Procol drummer-turned-vocalist, Bobby Harrison – joined to play keyboards. Throughout these comings and goings, Procol Harum trundled on, never making bad records, while never threatening to rekindle the flames of 1967. They had one memorable moment, however, when they played a concert in Edmonton, Canada, with the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra in November 1971. The concert was recorded for a live album, and the version of Conquistador gave them their first hit single for nearly five years on both sides of the Atlantic, reaching the US Number 16 and UK Number 22 positions.

They were in the British charts again three years later at Number 16 with Pandora’s Box from Procol’s Ninth (1975), which was produced for them by Leiber and Stoller. In 1977, probably worn down by their consistent failure to make a significant commercial breakthrough, Procol Harum split up, leaving Something Magic as an inappropriately-titled farewell. Lyricist Keith Reid went into management and some of the others turned their hands to session work, while Gary Brooker combined the keyboard-playing role in Eric Clapton’s band with a solo career which in the early Eighties yielded two albums, No Fear Of Flying and Lead Me To The Water. On its US release, the latter was accompanied by publicity shrieking A Whiter Shade Of Success. Some folks just won’t let a chap forget.

Procol Harum: Recommended Listening

A Whiter Shade of Pale, A Salty Dog (Cube TOOFA 7, double album)

(Includes: A Whiter Shade of Pale, Conquistador, Kaleidoscope,

Salad Days, Salty Dog, Wreck Of The Hesperus).

Thanks Jill, for the typing

More Procol in print at 'Beyond the Pale'

|

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |