Procol Harum : Nothing's Better Left

Unsaid

Jonathan Lewis in DISCoveries

magazine, January 1992

This is part of a good-sized trove of Procol cuttings lately

re-discovered, in a good state of preservation, by Paler Paul Wolfe. We hope to

bring you more from his excellent collection in weeks to come. Many thanks for

the scans, Paul!

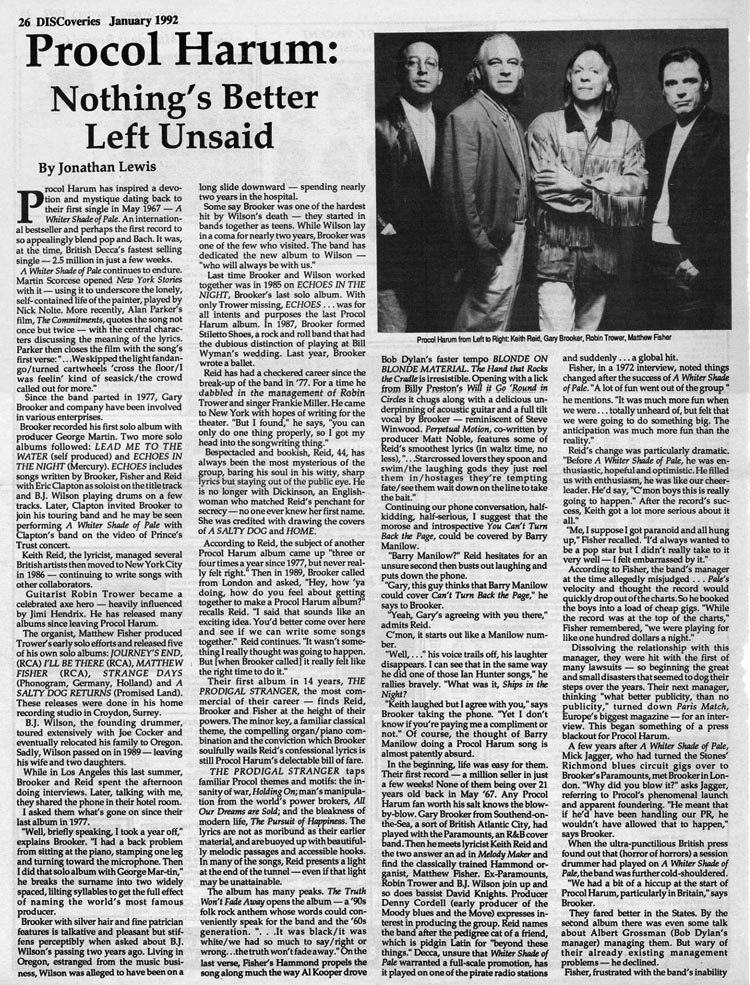

Procol Harum has inspired a devotion and mystique dating back to their first

single in May 1967 – A

Whiter Shade of Pale. An international bestseller and perhaps the first

record to so appealingly blend pop and Bach. It was, at the time, British

Decca’s fastest selling single – 2.5 million in just a few weeks.

Procol Harum has inspired a devotion and mystique dating back to their first

single in May 1967 – A

Whiter Shade of Pale. An international bestseller and perhaps the first

record to so appealingly blend pop and Bach. It was, at the time, British

Decca’s fastest selling single – 2.5 million in just a few weeks.

A Whiter Shade of Pale

continues to endure. Martin Scorsese opened New York Stories with it – using it to underscore the lonely, self- contained life of the painter, played

by Nick Nolte. More recently, Alan Parker’s film, The Commitments, quotes

the song not once but twice – with the central characters discussing the meaning

of the lyrics. Parker then closes the film with the song’s first verse:’ We

skipped the light fandango / turned cartwheels ‘cross the floor / I was feeling

kind of seasick / the crowd called out for more.’

Since the band parted in 1977,

Gary Brooker and company have been involved in various enterprises.

Brooker recorded his first solo

album with producer George Martin. Two more solo albums followed: Lead Me to

the Water (self-produced) and Echoes in the Night (Mercury).

Echoes

includes songs written by Brooker, Fisher and Reid with Eric Clapton as soloist

on the title track and BJ Wilson playing drums on a few tracks. Later, Clapton

invited Brooker to join his touring band and he may be seen performing A

Whiter Shade of Pale with Clapton’s band on the video of Prince’s Trust

concert.

Keith Reid, the lyricist, managed

several British artists then moved to New York City in 1986 – continuing to

write songs with other collaborators.

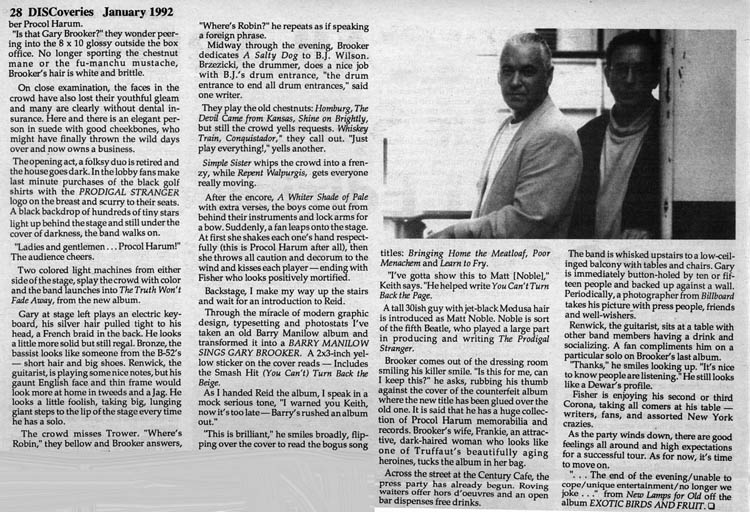

Guitarist Robin Trower became a

celebrated axe hero – heavily influenced by Jimi Hendrix. He has released many

albums since leaving Procol Harum.

The organist, Matthew Fisher,

produced Trower’s early solo efforts and released five of his own solo albums:

Journey’s End, (RCA) I’ll Be There (RCA), Matthew Fisher

(RCA), Strange Days (Phonogram, Germany, Holland) and A Salty Dog

Returns (Promised Land). These releases were done [sic] in his home

recording studio in Croydon, Surrey.

BJ Wilson, the founding drummer,

toured extensively with Joe Cocker and eventually relocated his family to

Oregon. Sadly, Wilson passed on in 1989 – leaving his wife and two daughters.

While in Los Angeles this last

summer, Brooker and Reid spent the afternoon doing interviews. Later, talking

with me, they shared the phone in their hotel room.

I asked them what’s gone on since

their last album in 1977.

‘Well, briefly speaking, I took a

year off,’ explains Brooker. ‘I had a back problem from sitting at the piano,

stamping one leg and turning toward the microphone. Then I did that solo album

with George Mar-tin.’ He breaks the surname into two widely spaced, lilting

syllables to get the full effect of naming the world’s most famous producer.

Brooker with silver hair and fine

patrician features is talkative and pleasant but stiffens perceptibly when asked

about BJ Wilson’s passing two years ago. Living in Oregon, estranged from the

music business, Wilson was alleged to have been on a long slide downward – spending nearly two years in the hospital.

Some say Brooker was one of the

hardest hit by Wilson’s death – they started in bands together as teens. While

Wilson lay in a coma for nearly two years, Brooker was one of the few who

visited. The band has dedicated the new album to Wilson – 'who will always be

with us.’

Last time Brooker and Wilson

worked together was in 1985 on Echoes in the Night, Brooker’s last solo

album. With only Trower missing, Echoes… was for [sic] all intents and

purposes the last Procol Harum album. In 1987, Brooker formed Stiletto Shoes

[sic], a rock and roll band that had the dubious distinction of playing at Bill

Wyman’s wedding. Last year, Brooker wrote a ballet.

Reid has had a checkered career

since the break-up of the band in ‘77. For a time he dabbled in the management

of Robin Trower and singer Frankie Miller. He came to New York with hopes of

writing for the theater. ‘But I found,’ he says, ‘you can only do one thing

properly, so I got my head into the songwriting thing.’

Bespectacled and bookish, Reid,

44, has always been the most mysterious of the group, baring his soul in his

witty, sharp lyrics but staying out of the public eye. He is no longer with

Dickinson, an Englishwoman who matched Reid’s penchant for secrecy – no one ever

knew her first name. She was credited with drawing the covers of A Salty Dog

and Home.

According to Reid, the subject of

another Procol Harum album came up ‘three or four times a year since 1977, but

never really felt right.’ Then in 1989, Brooker called from London and asked,

‘Hey, how ya doing, how do you feel about getting together to make a Procol

Harum album?’ recalls Reid. ‘I said that sounds like an exciting idea. You’d

better come over here and see if we can write some songs together, ‘ Reid

continues. ‘It wasn’t something I really thought was going to happen. But [when

Brooker called] it really felt like the right time to do it.’

Their first album in fourteen

years, The Prodigal Stranger, the most commercial of their career, finds

Reid, Brooker and Fisher at the height of their powers. The minor key, a

familiar classical theme, the compelling organ/piano combination and the

conviction which [sic] Brooker soulfully wails Reid’s confessional lyrics is

still Procol Harum’s delectable bill of fare.

The Prodigal Stranger

taps familiar Procol themes and motifs: the insanity of war, Holding On;

man’s manipulation from [sic] the world’s power brokers, All Our Dreams are

Sold; and the bleakness of modern life, The Pursuit of Happiness. The

lyrics are not as moribund as their earlier material, and are buoyed up with

beautifully melodic passages and accessible hooks. In many of the songs, Reid

presents a light at the end of the tunnel – even if that light may be

unattainable.

The album has many peaks. The

Truth Won’t Fade Away opens the album – a ‘90s folk rock anthem whose words

could conveniently speak for the band and the ‘60s generation. ‘It was black/it

was white/we had so much to say/right or wrong. The truth won’t fade away.’ On

the last verse, Fisher’s Hammond propels the song along much the way Al Kooper

drove Bob Dylan’s faster tempo Blonde On Blonde material. The Hand

that Rocks the Cradle is irresistible. Opening with a lick from Billy

Preston’s Will it Go ‘Round in Circles, it chugs along with a delicious

underpinning of acoustic guitar and a full tilt vocal by Brooker – reminiscent

of Steve Winwood. Perpetual Motion, co-written by producer Matt Noble,

features some of Reid’s smoothest lyrics (in waltz time, no less), ‘…

Starcrossed lovers they spoon and swim/the laughing gods they just reel them

in/hostages they’re tempting fate/see them wait down on the line to take the

bait.’

Continuing our phone

conversation, half-kidding, half-serious, I suggest that the morose and

introspective You Can’t Turn Back the Page could be covered by Barry

Manilow.

‘Barry Manilow?’ Reid hesitates

for an unsure second then busts out laughing and puts down the phone.

‘Gary, this guy thinks that Barry

Manilow could cover Can’t Turn Back the Page, he says to Brooker.

‘Yeah, Gary’s agreeing with you

there,’ admits Reid.

C’mon, it starts out like a

Manilow number.

‘Well …’ his voice trails off,

his laughter disappears. ‘I can see that in the same way he did one of those Ian

Hunter songs,’ he rallies bravely. ‘What was it, Ships in the Night?’

‘Keith laughed but I agree with

you,’ says Brooker, taking the phone. ‘Yet I don’t know if you’re paying me a

compliment or not.’ Of course, the thought of Barry Manilow doing a Procol Harum

song is almost patently absurd.

In the beginning, life was easy

for them. Their first record – a million seller in just a few weeks! None of

them [sic] being over 21 years old back in May ‘67. Any Procol Harum fan worth

his salt knows the blow-by-blow. Gary Brooker from Southend-on-the-Sea [sic], a

sort of British Atlantic City, had played with The Paramounts, an R&B cover

band. Then he meets lyricist Keith Reid and the two answer an ad in Melody

Maker and find the classically trained Hammond organist, Matthew Fisher.

Ex-Paramounts Robin Trower and BJ Wilson join up and so does bassist David

Knights. Producer Denny Cordell (early producer of the Moody Blues and the Move)

expresses interest in producing the group. Reid names the band after the

pedigree cat of a friend, which is pidgin Latin for ‘beyond these things.’

Decca, unsure that Whiter Shade of Pale warranted a full-scale promotion,

has it played on one of the pirate radio stations and suddenly … a global hit.

Fisher, in a 1972 interview,

noted things changed after the success of A Whiter Shade of Pale. ‘A lot

of fun went out of the group,’ he mentions. ‘It was much more fun when we were

totally unheard of, but felt that we were going to do something big. The

anticipation was much more fun than the reality.’

Reid’s change was particularly

dramatic. ‘Before A Whiter Shade of Pale, he was enthusiastic, hopeful

and optimistic. He filled us with enthusiasm, he was like our cheerleader. He’d

say, “C’mon boys, this is really going to happen.” After the record’s success,

Keith got a lot more serious about it all.’

‘Me, I suppose I got paranoid and

all hung up,’ Fisher recalled. ‘I’d always wanted to be a pop star but I didn’t

really take to it very well – I felt embarrassed by it.’

According to Fisher, the band’s

manager at the time allegedly misjudged … Pale’s velocity and thought the

record would quickly drop out of the charts. So he booked the boys into a load

of cheap gigs. ‘While the record was at the top of the charts,’ Fisher

remembered, ‘we were playing for like one hundred dollars a night.’

Dissolving the relationship with

this manager, they were hit with the first of many lawsuits – so beginning the

great and small disasters that seemed to dog their steps over the years. Their

next manager, thinking ‘what better publicity, than no publicity?’ turned down

Paris Match, Europe’s biggest magazine – for an interview. This began

something of a press blackout for Procol Harum.

A few years after A Whiter

Shade of Pale, Mick Jagger, who had turned the Stones’ Richmond blues

circuit gigs over to Brooker’s Paramounts, met Brooker in London. ‘Why did you

blow it?’ asks Jagger, referring to Procol’s phenomenal launch and apparent

foundering. ‘He meant that if he’d have been handling our PR, he wouldn’t have

allowed that to happen,’ says Brooker.

When the ultra-punctilious

British press found out that (horror of horrors) a session drummer had played on

A Whiter Shade of Pale, the band was further cold-shouldered.

‘We had a bit of a hiccup at the

start of Procol Harum, particularly in Britain,’ says Brooker.

They fared better in the States.

By the second album there was even some talk about Albert Grossman (Bob Dylan’s

manager) managing them. But, wary of their already existing management problems,

he declined.

Fisher, frustrated with the

band’s inability to achieve solid management and chart success, left the band

after producing their most successful album of original material, A Salty Dog.

Bassist David Knights left shortly thereafter.

Other discontentment lurked

within the band. No longer satisfied as just a player, Trower began to take more

of a part shaping Procol Harum’s sound. He started moving the group away from

its keyboard-dominated sound with songs like Whiskey [sic] Train – attracting an even broader audience. After two guitar-dominated albums,

Broken Barricades and Home, Trower left to pursue a solo career.

Scrambling to put the band back

together, Chris Copping, another ex- Paramount, was recruited for organ and

bass. Dave Ball, a young guitarist, was also hired. Along with bassist Alan

Cartwright, they recorded Procol Harum live in Concert with the Edmonton

Symphony Orchestra. A live single from this album, Conquistador, went

up the charts – but Dave Ball soon departed.

Scrambling to put the band back

together, Chris Copping, another ex- Paramount, was recruited for organ and

bass. Dave Ball, a young guitarist, was also hired. Along with bassist Alan

Cartwright, they recorded Procol Harum live in Concert with the Edmonton

Symphony Orchestra. A live single from this album, Conquistador, went

up the charts – but Dave Ball soon departed.

Their next album, Grand Hotel,

was one of their most ambitious. The songs, alternately spare and full-blown

with orchestra and chorale, featured a new and exciting guitarist. Mick Grabham

was perhaps the only one who could fill Trower’s shoes and take things in a more

melodic direction. His emotive but restrained playing graced their last four

albums.

In 1973, winds of change were

blowing across the music business. Disco was poised to narcotize the public and

singles were suddenly becoming more important to a band’s success. At the time

both Reid and Brooker felt that the wrong single was picked from Grand Hotel.

‘In retrospect,’ Reid recalls

wryly, ‘I don’t think there was a single.’

The album did well in Europe but

America didn’t warm to it – signally [sic] the beginning of Procol Harum’s

decline. It might have been better to leave after Grand Hotel, a

decidedly high note with such gems as the malevolent Toujours L’amours

[sic] and the romantic Rum Tale. They soldiered on for another three

albums.

The album Exotic Birds and

Fruit still showed flashes of brilliance. Strong as Samson

inaugurated Reid’s own protest type song with lines like, ‘psychiatrists and

lawyers/destroying mankind/driving them crazy/and stealing them blind.’

Beyond the Pale

(no connection with A Whiter Shade of Pale) married a story about

searching for the Holy Grail with a gypsyish folk melody. ‘It’s kind of Eastern

European,’ Brooker says. ‘It does pop up now and again. I guess one of the Liszt

pieces is always banging around in my head.’

Running out of ideas for their

ninth album, Procol’s Ninth, they enlisted the legendary

songwriters/producers, Lieber and Stollar [sic]. According to Brooker, the album

allegedly became a tug of war between Lieber and Stollar [sic]. They wanted the

band to record a bunch of their originals and Procol Harum were dead set on

recording only their own material. Pandora’s Box, a song from the band’s

infancy, was a hit in Europe while Brooker gave Lieber and Stollar’s [sic[ I

Keep Forgetting a spirited and wailing read.

The last album, Something

Magic, was a morass of obfuscation and obscurity. The entire second side was

a spoken, dense parable.

After ten albums, and almost ten

years, they decided to ‘knock it on the head’ as Brooker put it – the group

disbanded.

The Camel sign no longer blows

smoke rings over Broadway. The combination of gusty wind and bright sun this

late-September day (1991) somehow conjures a more innocent ‘60s Big Apple. This

evening, Procol Harum will kick off the first American date in their showcase

tour (just a handful of cities to let people know the album is out). There is an

air of expectation as this is their first tour in fourteen years and Fisher’s

first tour with the band in more than twenty years. The West Coast contingent of

their new record label has flown in, as has Mick Brigdon, an old school friend

of Brooker’s currently working on the band’s account with Bill Graham

Management. The night before, WNEW-FM broadcast a live, mini-concert from

Electric Ladyland Studios – by all accounts the magic was still there. Even

Denny Cordell has popped up for a visit.

The band has been booked into the

Paramount Hotel on 46th Street – a trendy, post-modern environment owned by

Studio 54’s Ian Schrager and designed by the ultimate in French designers,

Phillipe Starck. With four-foot stainless steel funnels for sinks (right out of

the Bauhaus), elevators bathed in kinky colored lights, and a

walk-on-the-wild-side lobby, this is the hottest new hotel in New York.

Matthew Fisher is not impressed.

‘There are no signs saying it’s a hotel," he cries exasperatedly into the phone.

‘The furniture is ridiculous and the rooms are too small.’ We recall the words

of Homburg, ‘ For the floor he [sic] found descended and the ceiling was

too tall.’

The hotel is on the outskirts of

the theater district. There is no sign with the name of the hotel. It is as if

in this last weary decade of the 20th century, signs have been deemed somehow

gauche. Sort of a hip corollary of, if you have to ask how much, you probably

can’t afford it – if you can’t find the hotel, maybe you don’t belong there.

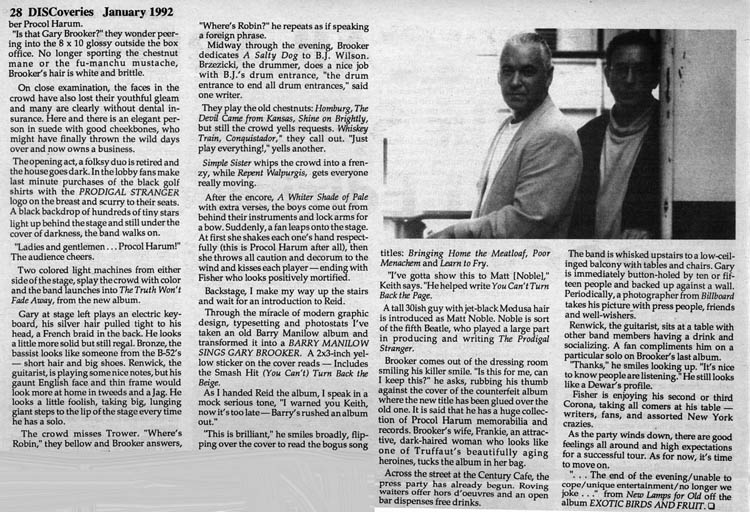

Fisher swings the door wide and

lunges out into the hallway, handshake outstretched to preclude any awkward hugs

(it is twenty years since I’ve seen him). The Beatle bangs are gone and his

features are sharper now. He still has a choir-boy look with his hair parting

down the middle. He is 45, trim, and dressed in jeans, running shoes and a

t-shirt.

He gestures, as if to dismiss the

tiny, condensed room which looks like a welfare hotel brought up to speed too

quickly. A big, empty, pretentious, gold frame forms the headboard of the bed. A

spiral notebook lies open on the little table filled with complex equations.

Fisher is a serious student of computer science. Still living and working in his

three-storey Croydon home he’s known since age sixteen, he is alternately

involved or fed up with the music business.

I toss a single on the bed in

order to continue a long standing tradition.

Twenty years ago I brought him,

at his request, Keep Your Hands Off of My Baby (Little Eva) and Clarence

Frogman Henry’s, (I Don’t Know Why I Love You) But I Do for his then

pregnant wife. (That child is now 19, and has a 15 year-old brother).

‘Oh, great,’ he smiles, picking

up Ketty Lester’s Love Letters, a record, he complained earlier he had

lost. ‘I’ll have to think of some clever way to pack this so it’s not damaged.’

‘He digs in his bag and comes up

with a reasonable trade – a homemade cassette of his next to last solo album

Strange Days, unreleased in the States.

We take the elevator down in

search of other band members in order to find out what time the soundcheck is

scheduled. In the lobby he finds Tim Renwick, the guitarist, who tells him the

sound check is at 4:00 – we have almost two hours. Looking for a coffee shop we

walk up 46th Street into the sun, dodging pedestrians, pirouetting around cars

on Broadway and talking all the way.

We end up at The Algonquin, that

great old New York hotel where the literary lions of the ‘40s, Dorothy Parker,

Nathanael Benchley and others, met weekly. As we approach, he notices another

hotel up the block and he remarks matter-of-factly, that’s where he spent his

honeymoon.

Fisher’s dungaree jacket stops us

from dining in the formal Rose Room where the Algonquin crowd hung out. So we

settle for the Blue Bar, just across the quaint lobby. Its red leather booths

are cozy [sic] and we have the small room to ourselves. A Spanish waiter brings

two espressos

When asked about his first

meeting with Brooker and Reid, Fisher replies, ‘I’d been at a gig the night

before and didn’t get home until 2:00 pm [sic]. They came by my house at 10:00

o’clock the next morning. The front room was completely filled with musical

junk. ‘They brought with them a demo, Conquistador/Salad Days, and

some lyric sheets, including A Whiter Shade of Pale. I really got into

Salad Days, I thought it was really a great song and on the strength of

that, there might be something there. I was quite impressed with Gary’s voice.

I then asked about the medieval

clothes the band wore for their first promotional photos. Fisher goes on to say,

‘The people who made the clothing made the clothes the Beatles wore on Sgt

Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. They promoted the fad that they were

friends of the Beatles. Rob was the only one who looked good in them. I felt

like a twit walking around in that garb. I threw it away as soon as I could.’

I asked about Mabel from

the first album and Fisher replied, ‘I kind of dug that. It’s a shame it was

never done in stereo because we were doing all kinds of things. We were sort of

wrecking the place; we had these big piles of chairs we were knocking over and

all the time had the mikes going. And [Denny] Cordell was running around with a

fire extinguisher!"

Besides the loss of BJ, only one

thing mars this Procol Harum reunion, Trower’s absence. A People magazine

piece reports that he will join the second leg of the tour next fall, but at the

moment, his absence is unexplained. From a sentimental standpoint, Fisher is

sorry Trower hasn’t joined up. ‘When Rob takes a solo,’ he says, ‘everyone

bloody well knows it.’ Still he is pleased with the Bronze / Brzezicki / Renwick

rhythm section.

Bronze and Renwick are old studio

hands with Brooker and Fisher. In 1985 they played on Brooker’s last solo,

Echoes in the Night. According to the credits, much of the

overdubbing was done at Fisher’s home studio.

Does that mean Eric Clapton, who

played on the title track, came down to Fisher’s house? ‘Oh, yeah,’ he smiles.

‘As a matter of fact, Gary

decided to go to lunch or something leaving me feeling very frightened [to

record Clapton’s solo].

‘As a matter of fact, Gary

decided to go to lunch or something leaving me feeling very frightened [to

record Clapton’s solo].

‘It was like, Gary, what am I

supposed to do? Tell him, Eric, could you take that solo again. That last one

was kind of crappy,’ he laughs.

He mentions with a hint of pride

that Clapton tried his own version of Echoes in the Night (which Fisher

co-wrote with Brooker and Reid) but in the end wasn’t happy with his vocal.

Another gem on that album was

A Trick in [sic] the Night, also written by Fisher, Brooker and Reid.

Though not particularly Procol Harum-ish, it is a sweet little number wherein

Fisher seems to have nailed the funky New York session sound of Steve Gadd and

company – a pack he respects.

No, he begs to differ. ‘The

inspiration for that,’ he smiles, ‘was a Little Feat song, Long Distance

Lover.

" I am not surprised to be so off

base. It was in a conversation just like this 20 years ago when he confessed the

idea for Repent Walpurgis, the brooding, Gothic instrumental that is his

signature piece didn’t come from Bach, Beethoven or Brahms, but rather Valli. As

in Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons, and their song Beggin’. He always

loved the ‘Seasons.

Suddenly, he looks at his watch.

Anxious to get back to the hotel, he suggests wrapping things up.

What are your future plans?

‘I’m quite keen on this Procol

thing,’ he says, surprising for someone who’s had an on and off again history

with the band.

Do you like the idea of more

touring?

‘Yeah, if there’s one thing in

this world I’m qualified to do, it’s blow organ with Procol Harum,’ a rare,

self-satisfied smile crossing his face. ‘Even Jimmy Smith [dean of the Hammond

organ] couldn’t do it better than me.’

On the way out of the Algonquin,

he stops in the lobby to pet a small cat curled up on one of the Louis XIV

chairs.

Later that night before the

concert, two giant arc lights search the night sky from a truck in front of Town

Hall. It’s a little chilly but the sidewalk is a sea of faces: long-haired

ex-hippie moms and dads smiling, motorcycle babes and others who remember Procol

Harum.

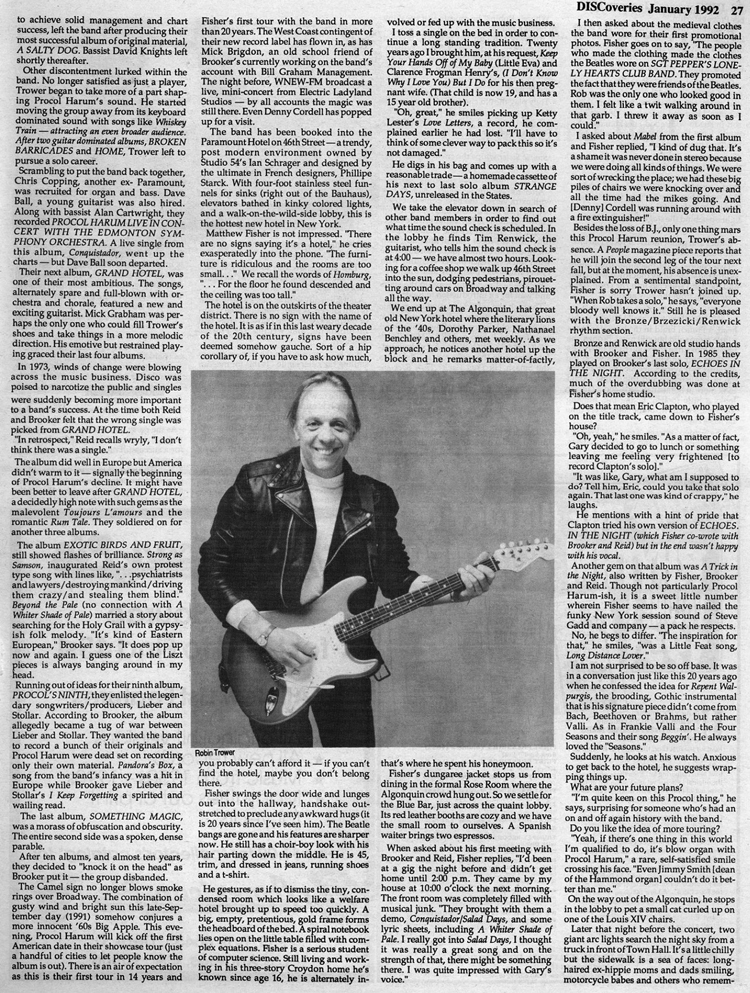

‘Is that Gary Brooker?’ they

wonder peering into the 8 x 10 glossy outside the box office. No longer sporting

the chestnut mane or the fu-manchu mustache, Brooker’s hair is white and

brittle.

On close examination, the faces

in the crowd have also lost their youthful gleam and many are clearly without

dental insurance. Here and there is an elegant person in suede with good

cheekbones, who might have finally thrown the wild days over and now owns a

business.

The opening act, a folksy duo is

retired and the house goes dark.

In the lobby fans make last

minute purchases of the black golf shirts with the Prodigal Stranger logo

on the breast and scurry to their seats. A black backdrop of hundreds of tiny

stars light up behind the stage and still under the cover of darkness, the band

walks on.

‘Ladies and gentlemen . Procol

Harum!’ The audience cheers.

Two colored light machines from

either side of the stage splay the crowd with color and the band launches into

The Truth Won’t Fade Away, from the new album.

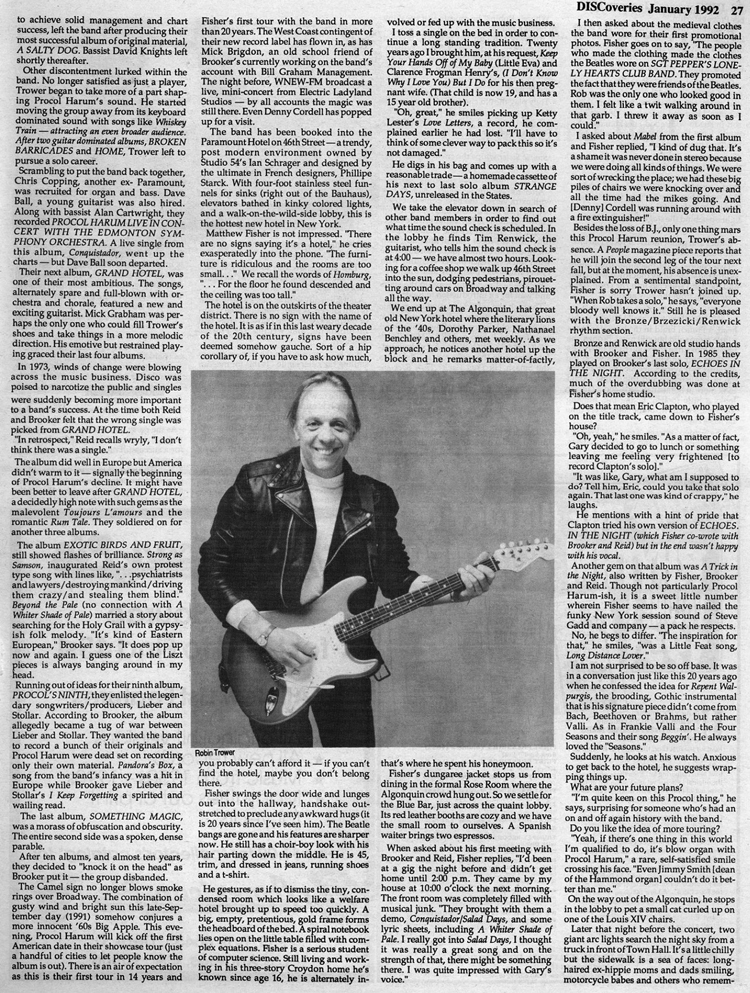

Gary at stage left plays an

electric keyboard, his silver hair pulled tight to his head, a French braid in

the back. He looks a little more solid but still regal. Bronze, the bassist

looks like someone from the B-52s – short hair and big shoes. Renwick, the

guitarist, is playing some nice notes, but his gaunt English face and thin frame

would look more at home in tweeds and a Jag. He looks a little foolish, taking

big, lunging giant steps to the lip of the stage every time he has a solo.

The crowd misses Trower. ‘Where’s

Robin,’ they bellow and Brooker answers, ‘Where’s Robin?’ he repeats as if

speaking a foreign phrase.

Midway through the evening,

Brooker dedicates A Salty Dog to BJ Wilson. Brzezicki, the drummer, does

a nice job with BJ’s drum entrance, ‘the drum entrance to end all drum

entrances,’ said one writer.

They play the old chestnuts:

Homburg, The Devil Came from Kansas, Shine on Brightly, but

still the crowd yells requests. ‘Whiskey Train, Conquistador,’

they call out. ‘Just play everything!’ yells another.

Simple Sister

whips the crowd into a frenzy, while Repent Walpurgis gets everyone

really moving.

After the encore, A Whiter

Shade of Pale with extra verses, the boys come out from behind their

instruments and lock arms for a bow. Suddenly, a fan leaps on to the stage. At

first she shakes each one’s hand respectfully (this is Procol Harum after all),

then she throws all caution and decorum to the wind and kisses each player – ending with Fisher who looks positively mortified.

Backstage, I make my way up the

stairs and wait for an introduction to Reid.

Through the miracle of modern

graphic design, typesetting and photostats I’ve taken an old Barry Manilow album

and transformed it into a Barry Manilow Sings Gary Brooker. A 2 x 3-inch

yellow sticker on the cover reads - Includes the Smash Hit (You Can’t) Turn

Back the Beige.

As I handed Reid the album, I

speak in a mock serious tone, ‘I warned you Keith, now it’s too late – Barry’s

rushed an album out.’

‘This is brilliant,’ he smiles

broadly, flipping over the cover to read the bogus song titles: Bringing Home

the Meatloaf, Poor Menachem and Learn to Fry.

‘I’ve gotta show this to Matt

[Noble],’ Keith says. ‘He helped write You Can’t Turn Back the Page.’

A tall 30ish guy with jet-black

Medusa hair is introduced as Matt Noble. Noble is sort of the fifth Beatle, who

played a large part in producing and writing The Prodigal Stranger.

Brooker comes out of the dressing

room smiling his killer smile.

‘Is this for me, can I keep

this?’ he asks, rubbing his thumb against the cover of the counterfeit album

where the new title has been glued over the old one. It is said that he has a

huge collection of Procol Harum memorabilia and records. Brooker’s wife, Frankie

[sic], an attractive, dark-haired woman who looks like one of Truffaut’s

beautifully aging heroines, tucks the album in her bag.

Across the street at the Century

Cafe, the press party has already begun. Roving waiters offer hors d’oeuvres and

an open bar dispenses free drinks. The band is whisked upstairs to a

low-ceilinged balcony with tables and chairs. Gary is immediately button-holed

by ten or fifteen people and backed up against a wall. Periodically, a

photographer from Billboard takes his picture with press people, friends

and well-wishers.

Renwick, the guitarist, sits at a

table with other band members having a drink and socializing A fan compliments

him on a particular solo on Brooker’s last album.

‘Thanks,’ he smiles looking up.

‘It’s nice to know people are listening.’ He still looks like a Dewar’s profile.

Fisher is enjoying his second or

third Corona, taking all comers at his table – writers, fans, and assorted New

York crazies.

As the party winds down, there

are good feelings all around and high expectations for a successful tour. As for

now, it’s time to move on.

‘ … The end of the evening/unable

to cope/unique entertainment/no longer we joke …’ from New Lamps for Old

off the album Exotic Birds and Fruit.

from the collection of Paul

Wolfe

Procol Harum has inspired a devotion and mystique dating back to their first

single in May 1967 – A

Whiter Shade of Pale. An international bestseller and perhaps the first

record to so appealingly blend pop and Bach. It was, at the time, British

Decca’s fastest selling single – 2.5 million in just a few weeks.

Procol Harum has inspired a devotion and mystique dating back to their first

single in May 1967 – A

Whiter Shade of Pale. An international bestseller and perhaps the first

record to so appealingly blend pop and Bach. It was, at the time, British

Decca’s fastest selling single – 2.5 million in just a few weeks.