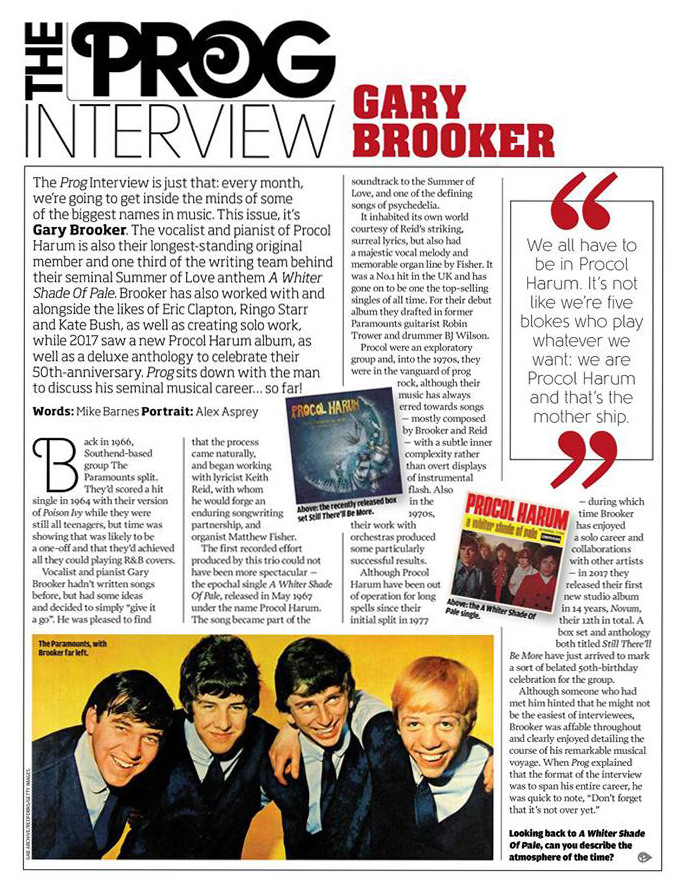

The Prog Interview is just that: every month, we’re going to get inside the minds of some of the biggest names in music. This issue, it’s Gary Brooker. The vocalist and pianist of Procol Harum is also their longest-standing original member and one third of the writing team behind their seminal Summer of Love anthem A Whiter Shade of Pale. Brooker has also worked with and alongside the likes of Eric Clapton, Ringo Starr and Kate Bush, as well as creating solo work, while 2017 saw a new Procol Harum album, as well as a deluxe anthology to celebrate their fiftieth anniversary. Prog sits down with the man to discuss his seminal musical career… so far!

Back in 1966, Southend-based group The

Paramounts split. They’d scored a hit single in 1964 with their version of

Poison Ivy while they were still all teenagers, but time was showing that

was likely to be a one-off and that they’d achieved all they could playing R&B

covers.

Back in 1966, Southend-based group The

Paramounts split. They’d scored a hit single in 1964 with their version of

Poison Ivy while they were still all teenagers, but time was showing that

was likely to be a one-off and that they’d achieved all they could playing R&B

covers.

Vocalist and pianist Gary Brooker hadn’t written songs before, but had some ideas and decided to simply “give it a go”. He was pleased to find that the process came naturally, and began working with lyricist Keith Reid, with whom he would forge an enduring song writing partnership, and organist Matthew Fisher.

The first recorded effort produced by this trio could not have been more spectacular – the epochal single A Whiter Shade of Pale, released in May 1967 under the name Procol Harum. The song became part of the soundtrack to the Summer of Love, and one of the defining songs of psychedelia.

It inhabited its own world courtesy of Reid’s striking, surreal lyrics, but also had a majestic vocal melody and memorable organ line by Fisher. It was a No 1 hit in the UK and has gone on to be one the top-selling singles of all time. For their debut album they drafted in former Paramounts guitarist Robin Trower and drummer BJ Wilson.

Procol were an exploratory group and, into the 1970s, they were in the vanguard of prog rock, although their music has always erred towards songs – mostly composed by Brooker and Reid – with a subtle inner complexity rather than overt displays of instrumental flash. Also in the 1970s, their work with orchestras produced some particularly successful results.

Although Procol Harum have been out of operation for long spells since their initial split in 1977 – during which time Brooker has enjoyed a solo career and collaborations with other artists – in 2017 they released their first new studio album in 14 years, Novum, their 12th in total. A box set and anthology both titled Still There’ll Be More have just arrived to mark a sort of belated 50th-birthday celebration for the group.

Although someone who had met him hinted that he might not be the easiest of interviewees, Brooker was affable throughout and clearly enjoyed detailing the course of his remarkable musical voyage. When Prog explained that the format of the interview was to span his entire career, he was quick to note, “Don’t forget that it’s not over yet.”

Looking back to A Whiter Shade of Pale, can you describe the atmosphere of the time?

The psychedelic era was really an expanding out and a realisation that you could, in that point in British music, do whatever you wanted. There didn’t seem to be any boundaries and if there were, you completely ignored them.

A Whiter Shade of Pale fitted into our idea at the time, which was to do something different. It was a long single. It was in fact longer to start with, because it had three verses. I think it was probably about seven minutes.

Somebody told me that they were playing nothing over 2:47 on the radio. I remember the figures! It wasn’t true: I think the public were up for as much of a change as the people creating things.

You followed it with Homburg, which

went to No 5 in the UK, but your chart success tailed off after. Was there

pressure to produce more hits?

You followed it with Homburg, which

went to No 5 in the UK, but your chart success tailed off after. Was there

pressure to produce more hits?

There was enormous pressure. Because A Whiter Shade Of Pale was so big on a world stage, people wanted another one, which was nigh on impossible as it came at a time when it just hit people’s ears and rang some sort of bell. And it’s always been a great mystery why it did that.

Peter Hammill has said that one of the songs that most influenced him was the 17-and-a-half minute In Held ’Twas In I from Procol’s 1968 album Shine On Brightly. He realised then that it was okay to write something of that kind of length and ambition. How did it come about?

If you throw yourself back then there was a lot more freedom. I mean, it was a forward-thinking idea but it was perfectly acceptable. You talk about Hammill, well, Pete Townshend heard that and felt the same. He told us once that he got the idea of Tommy from that piece.

Might I even say that it was ‘progressive’, because the word existed, but it was not a pigeonhole that you could put bands into. In Held ’Twas In I, you certainly couldn’t call it pop, it would be hard to call it rock. There’s only one pigeonhole that we ever fitted into and that’s Procol Harum.

It’s got a lot of strange pieces that we knitted together, but you can get some kind of story out of it. It starts off with the beginning of the universe, really, if that’s possible. There’s some of a Buddhist chant and it ends up going to Heaven. It’s even got drug addiction in the middle.

The style that most people associate with the group was established in 1969 with A Salty Dog – that mix of bluesy earthiness with a grand, dramatic sweep.

It gets somewhere, doesn’t it? Well, that did kind of cement us, in our own minds as well. Strings had often been used on record, but it combined a song with an orchestral setting. We play the title track today and it’s as big as A Whiter Shade Of Pale to the audience.

When people talk about what fed into 70s progressive rock, very few mention the influences of R&B and soul, although many of the musicians grew up playing that music. But in Procol Harum’s music, that influence is overt. Would you agree?

I see what you’re saying there. Music to me is about conveying an emotion and you get that from having grown up with Ray Charles and Little Richard and Sam Cooke.

That

thread runs through and as you say, it’s not always identified. But what’s often

not at the front of these prog rock bands is first-class vocals. You might,

overall, get a good recording with marvellous, clever playing, but at the end of

the day the vocalist has got away with quite a bit. You got it with Traffic

because Steve Winwood followed that path and had grown up with those same

influences and, if you like, he can be a soul singer when he wants to.

That

thread runs through and as you say, it’s not always identified. But what’s often

not at the front of these prog rock bands is first-class vocals. You might,

overall, get a good recording with marvellous, clever playing, but at the end of

the day the vocalist has got away with quite a bit. You got it with Traffic

because Steve Winwood followed that path and had grown up with those same

influences and, if you like, he can be a soul singer when he wants to.

Your 1971 album Broken Barricades features a lot of Robin Trower’s flamboyant lead guitar playing. It was also his last album with the group before he embarked on a solo career. Did he let himself off the leash, or was he proving a point, perhaps?

I think it just happened organically. On A Salty Dog we let the organist, Matthew Fisher, be in charge of the production and he did a good job. Then he left and if you listen to Broken Barricades, there’s hardly any organ on it at all. And that bit more space allowed Trower to come to the fore.

Robin Trower got involved in the writing a bit more. He did at least three on Broken Barricades. He was always a great guitarist but he had to invent a different way of playing for the music that I’d written for Procol’s first, second and third albums. It wasn’t an easy twang-along; the easy part of it was that he had to play a blues solo and it sounded right. But when he couldn’t figure out the chord, or if it’s in E Flat, which guitarists don’t like, he would just find a good low guitar note that would vibrate through it all. Brian May does it all the time with Queen but Trower invented that.

Your former manager Chris Wright has stated that the live album Procol Harum recorded with the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra, released in 1972, “completely regenerated your career”. Is that accurate?

At the end of the day, yes. We were selling albums in America, not here. Here, they pretty much lost it around the time of Shine On Brightly. With Trower we did play once with an orchestra and choir in Stratford, Ontario, which was the first time we’d done it live. We didn’t play much, just In Held ’Twas In I and A Salty Dog, I think. But it was a tumultuous reception and a lot of people were there, and that led on to an invite from the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra.

We just did it at the end of the tour. I wrote out the orchestrations and Trower did what he did on the recorded versions. But he never really liked the idea.

You couldn’t play loud when you’re with an orchestra, so he had to have a tiny little amp that was a big as a radio. He did it, fair enough, and it was very impressive, but it was not his idea of what a group should be doing. So he left and we got in a new guitarist, Dave Ball.

And that was when Edmonton said, “Would you like to come and play?” and Chris Wright said, “Yes.” Everyone said, “Yes, we’d like to do it.” It was done wholeheartedly.