Procol HarumBeyond

|

|

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |

|

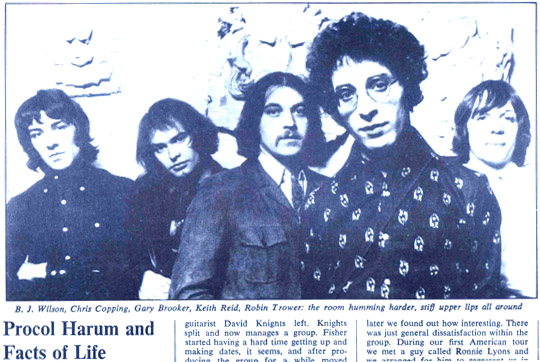

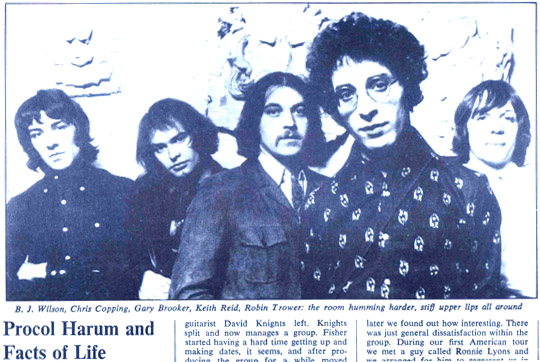

LONDON - It was easy to look into the log fire glowing in the once-grand fireplace and drift away into the world of vestal virgins, turning cartwheels cross the floor. The room was humming harder as the ceiling flew away. When we called out for another drink, the waiter brought a tray. And so it was that later, as the miller told his tale, that her face at first just ghostly, turned a whiter shade of pale.

But right across the room from the fire is Gary Brooker; his face peering over the top of a tatty piano, stuck all over with limpet-mikes wired up to a big amp. As the rest of Procol Harum twiddle guitar strings and adjust a cymbal stand, Gary counts them into the hundredth run-through of a track of the group's sixth [sic] album, Broken Barricades. Studious preparations for Procol's recent visit to America. Their ninth visit to the States, but it wasn't until a few months ago that Procol did their first British concert tour.

"It's a question of supply and demand, innit?" says BJ Wilson, getting up from behind his drums to pour out the hundredth cup of tea. "We could supply alright, but there isn't the demand."

"It's a fact of life, innit?" Robin Trower asks himself, easing out of his guitar strap and picking up some tea.

"Quite frankly," says Gary Brooker, in a tone that hints it's time to change the subject, "all our real work comes from America."

Procol Harum seem unconcerned with the fact of life that the minor cultization of the group in America just hasn't happened here. With the tenacity of a father-son word association, Procol Harum are still only known here as the creators of Whiter Shade of Pale, the classic of spring-summer 1967, that vibrated with the mood of the times more cunningly than any amount of contrived advertising and public relations could have accounted for.

It's not really that Procol are unconcerned about their British following being overwhelmingly nostalgic. There is a reason for it. And Procol knows all about it.

Finally playing their first proper British tour hasn't left the group with any delusions about a "comeback." They never really had anything to come back to. Gary points out that if it wasn't for signing with Chrysalis, who also manages the tour's bill topper - Jethro Tull - then it might never have come off.

"To be basic," adds Gary, "probably the only reason why we were on that tour was because there was nobody else around. It was all due to circumstances really. If there'd been someone else around, like the Kinks, we probably wouldn't have done it."

"You think it does you good to get exposed," says BJ, playing around with his empty tea cup and looking in it for inspiration. "But really ... what's the point?"

"On reflection we might not have done it," says Chris Copping, the group's newest member. He joined after Matthew Fisher, the original organist, and bass guitarist David Knights left. Knights split and now manages a group. Fisher started having a hard time getting up and making dates, it seems, and after producing the group for a while moved right away to a demo studio in South London where, according to the group, he still works. Copping doubles on bass and organ. In some numbers, he plays organ with one hand and a Fender keyboard bass, which has a church organ sound, with the other. Lead guitarist Robin Trower also doubles on bass.

"Yeah, we might not have done it, if we'd known," agrees Gary. "I mean all those people go into the concert hall with memories. They know exactly why they're there for and what they want to hear and we have to give it to them."

The trouble with talking to Procol Harum is that sooner or later the conversation returns to Whiter Shade of Pale. All roads lead to it. Like avoiding looking somebody in their glass eye. It's almost embarrassing

Nostalgia or whatever, Procol's British tour did put their name back in the second-page headlines. "Don't think we went down badly or anything," says Gary. "Surprised, really, just how well we did go down."

*

Right from the beginning, there's been confusion around Procol. Who manages them (at least three names are mentioned)? Who produces them (another three names)? Wasn't that somebody else playing organ on the record? Who is Keith Reid? Wasn't Whiter Shade of Pale based on a classical theme? Where are they now?

"Me and Keith wrote several songs together," explains Gary. "So, as was the thing, we got a few musicians together and hired a demo studio. Guy Stevens [who later became involved in Island Records] helped us work on the sessions and one of the songs we cut was Whiter Shade of Pale. It was exactly like the single that was released later, except less well recorded, naturally. Guy sort of managed us for a while and took the record round to various people, one of whom was Denny Cordell.

"A guy called Jonathan Weston was our first real manager. He had the first full five-piece. I think it was Cordell who suggested Weston as a manager. We used a session drummer, so before we could work we had to complete building the band. After the single came out, we waited a couple of weeks, saw what was happening and then went to cut an album.

"Well, we'd nearly finished the bloody album when it came to our notice that the drummer and guitarist were working in the opposite direction to the rest of us. So we got rid of them and got in Robin and BJ At about that time we began to have similar feelings about Mister Weston's direction. So we got rid of him too. Now all this involved great lawsuits and expense.

"Also it happened at the same time as what looked like the great 'Procol Split', which must have made people wonder what was happening so soon after a big hit.

"So we ended up signing with Tony Secunda, who was doing interesting things with the Move. Three months later we found out how interesting. There was just general dissatisfaction within the group. During our first American tour we met a guy called Ronnie Lyons and we arranged for him to represent us in the States after we had moved away from Secunda.

"Anyway, one of the results of all this is that our first album, Procol Harum, was held up. We finished it in five weeks, right on the tail of Whiter Shade of Pale, and it didn't come out for 18 months ... a year and a half." The album came out quickly in America, sold pretty well and got the band off to a good start, but here it was question time. "Whatever happened to Procol Harum?" The one-hit wonders.

"It was at that point," declared Gary, "that we lost the British audience."

It didn't help changing managers so quickly. Agents were a bit wary of the confused situation and held off on bookings. Time was running out for Procol.

The first album had been in mono and they were aware that in post-Sgt. Pepper days, albums had to be really produced.

"We were making our second album, Shine On Brightly, and were on the last track. Seventeen minutes long and just building up to the finale, when Denny Cordell goes to America. We'd nearly finished. It affected the quality of the album a bit but what really hurt was the release delay of three months. Again, we'd lost out. Though the second single, Homburg, was a sizeable hit, we came back from America, looked around and saw that it was dead here."

They parted contractually from Secunda in the beginning of 1969 but Gary says the spiritual break was some six months previous. "There was no confidence in us by promoters and we didn't work here much," says Gary. Meanwhile, they still had American representation and carried on touring there.

There's almost an excess of stiff-upper lips around when Procol talk about missed opportunities. No, they don't feel particularly bitter. Or surprised.

"Let's face it," says Robin. "The unusual case is a group that hasn't been fucked around. All these things have cost us money, you know. We always say, 'Right, this time we'll fight and go to court.' But it always ends up costing us money settling out of court."

"The drag is," adds BJ, "that it's happened to us three times."

Three times?

"Yeah, you see we're breaking away from Lyons and this other feller. They worked for their money OK, it's just that there's a small dispute over some accounting. It's all fixed now. The problem about any sort of managerial problems is that you'd be stupid to carry on working with somebody who you think is bad for you. Yet it would be even more stupid to stop work altogether. And to go to court costs a lot of money, because it's not always the right side, morally, that wins in contractual cases. But with the Lyons case we decided to fight it to the end. To make a stand. Of course, we ended up settling out of court."

"It's a fact of life, innit?" says Robin.

*

The fire had gone out and Procol were preparing to go home for food. Chris wanted to go and see a local folk club. The others were more interested in the TV and perhaps a drink in nearby Southend, day-trippers' delight on the mouth of the Thames. On a summer's weekend its pleasure pier (one and a half miles long - the biggest in the world) is swarming with East Enders bent on orgies of beer and fish and chips.

"There's another reason," says Chris, as he tidies up, "why we're out of place in England. When you think about it, we're one of the only British bands. None of us is featured, particularly good-looking or even recognizable. We haven't an Eric or an Alvin. Most British groups fall down over that sort of one-man thing. They don't play songs, like we do. And in the end it's the song that matters, isn't it?"

"There's too many jazzers around," says BJ, "Trying to improvise the whole time. The trouble is they don't improvise within the framework of a song and so it all sounds the same. That's true, isn't it?"

Procol Harum agree that it's true. Gary reckons that their lyrics have more importance attached to them in the States. They are used to freshmen on their first rock essay assignment asking them to explain the significance of Keith Reid's words.

"I mean, it's great and all that," BJ, "But Keith just writes them quickly - I don't think he spends much time on them. His stuff is a few levels of consciousness below the spoken word form and it's pointless trying to make literal sense out of them."

Normally Keith is around with the group for most of the time. His thin Randy Newman figure can be seen busily running around the back of a hall at a Procol concert, balancing sound, adjusting speakers. It's agreed that Keith is just like another member of the group.

As a parting shot, before he goes out to his slightly disreputable looking Jaguar, Gary says, "What we felt about Britain is this. We can't go round playing the little clubs. We can't go round playing support for bigger acts because that sort of exposure we don't need. We've been around too long and it would look like sympathy. And we can't top the bill ourselves because ... because, let's face it, three thousand people just aren't going to turn up on a Thursday.

"The solution is a piece of black plastic about seven inches across. We started off as a singles group, at the time when singles were the big thing and we've ended up as an album group. Whiter Shade of Pale was one of the last big singles of the era."

"It's a fact of life, innit?" says Robin.

Contributed by Marvin Chassman

Subscribe

to Rolling Stone Magazine here ![]()

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |