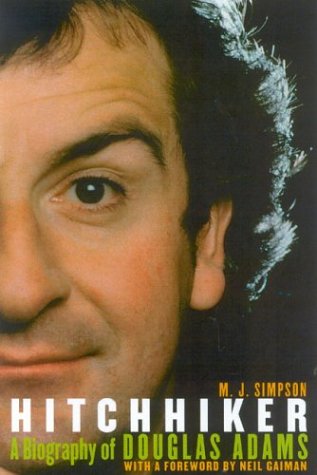

'Hitchhiker : a biography of Douglas Adams'

Procol-oriented extracts from MJ

Simpson's authoritative book (2)

The most famous Procol Harum fan (and the only one to cross

the footlights and perform with the band!) was Douglas Adams, the great British

comic writer, technophile and conservationist. 'Beyond the Pale' wholeheartedly

recommends Palers to buy MJ Simpson's fine, occasionally controversial,

biography of Douglas (not just because we get name-checked!). Click directly on

these links to have your copies delivered from

Amazon Canada,

Amazon UK,

Amazon Germany or

Amazon USA

From

‘Hitchhiker, a biography of Douglas Adams’ by MJ Simpson, Hodder and

Stoughton © 2003, pp 112-113

From

‘Hitchhiker, a biography of Douglas Adams’ by MJ Simpson, Hodder and

Stoughton © 2003, pp 112-113

It was on 29 March 1978 that Radio 4 listeners first discovered the Answer

to the Great Question of Life, the Universe and Everything. From then on,

Douglas was plagued by people pointing out meaningless coincidences or simply

failing to understand the bathos of the joke. When pressed, he gave various

explanations of how that particular number was arrived at - which, it should be

stressed, are . not explanations of what it means. It doesn't mean anything.

'If you're a comedy writer working in numbers you use a

number that's funny, like 17¾ or whatever,' said Douglas. 'But I thought to

myself that, if the major joke is the answer to life, the universe and

everything and it turns out to be a number, that has got to be a strong joke. If

you put a weak joke in the middle of it by saying not only is it a number but

it's 17¾, it slightly undermines it. I think the point is to have complete faith

in the strong joke and put the least funny number you can think of in the middle

of it. What is the most ordinary, workaday number you can find? I don't want

fractions on the end of it. I don't even want it to be a prime number. And I

guess it mustn't even be an odd number. There is something slightly more

reassuring about even numbers. So I just wanted an ordinary, workaday number,

and chose 42. It's an un frightening number. It's a number you could take home

and show to your parents.'!

Other times he was not so loquacious: 'It was a joke. It

had to be a number, an ordinary, smallish number, and I chose that one. I sat

at my desk, stared into the garden, and thought, 42 will do.’ I typed it out.

End of story.'

Very occasionally, Douglas let slip that there was a

history to the number, involving John Cleese. In one of his last ever

interviews, he revealed that Procol Harum also played their part: 'There's a

story on one Procol Harum track of someone going off to find enlightenment and

there's a bathetic answer. So it occurred to me that you take the question and

build it and build it and build it and then the answer is a number - completely

banal. It should be a number of no significance, part of the joke. I remember

working as a prop-borrower on a Video Arts training film and John Cleese was

playing a negligent bank teller adding up a column of numbers who pays no

attention to a customer who goes off to a good bank teller. And as he passes

John again on the way out John comes up with the figure he had been adding up.

There had been a lot of discussion at lunchtime as to what that should be and I

seem to remember the most ordinary number was thought to be 42.'

There are still further layers to this story. In a

posthumous collection of Graham Chapman material, Graham Crackers (edited

by Tim Yoakum), it was claimed that Chapman, who was not on that Video Arts

shoot, had suggested 42 to Douglas as the answer to life, the universe and

everything.

When asked about this, Douglas replied flatly: 'It's

completely untrue.' But after Douglas' [yes, the editor

has opted for this irregular form of the possessive throughout the volume]

death, when John Cleese was asked to verify the Video Arts anecdote, he claimed

that he and Chapman had originally come up with 42 as the funniest number when

they were first writing together in the 1960s.

Perhaps it's true, as Douglas often claimed that 42 is

simply the funniest two-digit number. 'The funniest three-digit number,' he once

pointed out, 'being 359.'

From

‘Hitchhiker, a biography of Douglas Adams’ by MJ Simpson, Hodder and

Stoughton © 2003, pp 112-113

From

‘Hitchhiker, a biography of Douglas Adams’ by MJ Simpson, Hodder and

Stoughton © 2003, pp 112-113