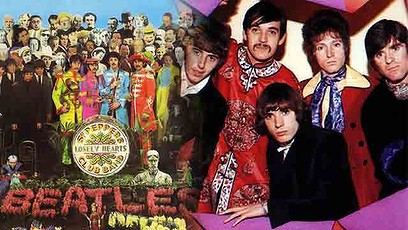

Age writer Warwick McFadyen takes a look all the way back to a time when Procol Harum and Sgt. Pepper ruled the charts.

It is June 10, 1967.

It is the first month of the summer of love in the northern hemisphere. Its centre is California.

But across the Atlantic, London is the centre of the musical universe.

It was a time of fracture and upheaval. A year before Timothy Leary had urged people to ‘‘turn on, tune in, drop out’’. Hundreds of thousands were marching against the Vietnam War, for civil rights — in the US, Northern Ireland and Australia, the Six-Day war between Israel and Egypt, Jordan and Syria began and ended, the generals took over Greece, Elvis married Priscilla.

To the youth of the day, who did not live under war clouds, the world was kaleidoscopic. They were ready, paradoxically, for A Whiter Shade of Pale. And so it came to pass.

On 10 June, Procol’s Harum’s debut single hit No. 1 on the British charts, where it set up home, inviting all to the slow dance under the mirror ball. It was a song enigma wrapped in a riddle wrapped in a mystery. Or one could just say it was just daft.

Procol Harum brought both sides of the generational gap together in just four minutes. The group merged a sensible organ — with a touch of Bach and high church about it — a discreet bass line and polite drumming (the guitar is mixed so low as to be not there) to a thin voice amplified by studio effects.

However, when Gary Brooker, in that angst-ridden, tinged with melancholy, dripping with regret, lonely young man’s voice sung [sic] the lyrics, it became the province of the young. For only the young could sing along, not care what the words meant and, yet, believe they were profound and spoke to each and everyone of them personally. Sing along, everyone knows the tune:

We skipped the light fandango

turned cartwheels cross the floor

I was feeling kinda seasick

but the crowd called out for more

The room was humming harder

as the ceiling flew away

When we called out for another drink

the waiter brought a tray

And so it was that later

as the miller told his tale

that her face, at first just ghostly,

turned a whiter shade of pale

She said, ‘There is no reason

and the truth is plain to see.’

But I wandered through my playing cards

and would not let her be.

One of sixteen vestal virgins

who were leaving for the coast

and although my eyes were open

they might have just as well’ve been closed.

One shouldn’t take it as a narrative or literally. It’s sonic impressionism. Lyricist Keith Reid spoke of its creation in terms of a painting. In an interview with Karen Dalton-Beninato, published on The Huffington Post website, he spoke of its artistic impressionistic qualities. ‘‘People never really get to the bottom of it. So it has some kind of mystery to it like a painting, you can always find new levels of meaning ... You can just kind of sit back and look at it endlessly.’’

How true. Millions have.

As well as its six weeks as No 1 in Britain it went to No 1

in Australia, among several countries, but only made it to No 5

in the US. Still, not bad for a debut. Introducing ‘‘the Procol

Harum’’, the announcer — a cleancut, neat chap in a sensible

suit — said on the BBC’s Top of the Pops, that while

some songs are gauged as standards because of the sales of its

sheet music (sheet music!), it could

be said that Whiter Shade of Pale, could be deemed both

a hit single, and a standard. It didn’t need the sheets.

The TV appearance is notable in the light of recent events.

Brooker is the star, playing piano, singing of vestal virgins,

but occasionally the camera pans to a fellow in a monk’s attire

with hood, organist Matthew Fisher.

Almost 40 years later, Fisher sued Brooker claiming that he was a co-author of the song and should be party to its royalties. The organ part, arguably the most identifiable thread to the piece, had been composed by him. It was based, he said, on Bach’s Air on a G String and Sleepers Awake. Brooker disagreed. The case worked its way through the High Court (where Fisher won), the Court of Appeal (where Brooker won) and then to the Law Lords, where Fisher seized back victory. He is to receive 40 per cent of the song’s royalties, but not retrospectively.

But Procol Harum suffered the danger of leaping to the heights too soon for what followed was a pale reflection of that first endeavour. The band had middling success afterwards, and carried on, with myriad personnel changes over the years, disbanding and reforming in fits and starts.

Still, for one instant in time, a spark became an enduring flame. A survey recently found that Whiter Shade of Pale was the most heard song in public places in Britain for the past 75 years, beating Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody and it was also the most played song on British radiowaves. It also regularly is listed as one of the greatest songs of pop music, has been covered almost 1000 times, and the phrase ‘‘a whiter shade of pale’’ is in the Oxford Dictionary of Modern Quotations.

For four minutes, it is the end of night, the drawing of the curtains, the last kiss before leaving, the walk down the aisle, the slow turning embrace on the dancefloor, the eternal song of the wedding. It is the enigma.

June 1967 was a strange and varied time; for while everyone was skipping lights fandango, they were also experiencing a revolution in their heads, courtesy of four lads from Liverpool. In June, Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was dropped onto an unsuspecting world. It was released in Britain at the start of the month and, by June 10, was No. 1 where it stayed unmoved, lord of all it surveyed, for the next five months. It was in the UK charts for almost three years. It resides in the cultural consciousness to this day.

The band’s producer and ‘‘fifth Beatle’’, Sir George Martin, speaking of Sgt Pepper, describes it as a ‘‘museum piece’’ in that it evoked the spirit of the times.

Sgt Pepper was both a sign of the times and a signpost to where music could lead, recorded on what now seems the most primitive of studio techniques, just four-track recorders.

It is often labelled rock’s first concept album, (an arguable description); though it might have started out that way in Paul McCartney’s mind, the result is not so much cohesion of concept as collective ideal.

Sgt Pepper was the full stop in the sentence the band had endured for the past three frenzied years. From 1963, they had conquered the world, but had, in doing so, driven themselves to exhaustion through touring. In 1966, they jumped off the treadmill, did various side projects such as John Lennon appearing in How I Won the War, and entered the studio.

The result, at first, was the double-A single Penny Lane and Strawberry Fields Forever. Sir George, in a British documentary on Sgt Pepper, says he had been asked by the group’s manager Brian Epstein for something to put out because ‘‘the boys need a lift’’. It was ‘‘one of the biggest errors I ever made’’ to hand over those two songs, Sir George lamented, thus depriving them from being on Sgt Pepper.

In the documentary, McCartney says the ‘‘theory’’ of Sgt Pepper, with its fictitious band, was that it could go on tour instead of them; so the world could let the Beatles be. But after the world heard the songs, that was never going to happen.

One of the geniuses — and it’s a work of many geniuses — is in its seamless weaving of a disparity of styles; from one song to another and within a song. Thus we move on side one from the title track to:

With a Little Help from My Friends

Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds

Getting Better

Fixing a Hole

She’s Leaving Home

Being for the Benefit of Mr Kite

Then to Side two:

Within You Without You

When I’m Sixty-Four

Lovely Rita

Good Morning Good Morning

Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise)

A Day in the Life

This was the flowering of a creative burst that had been evolving on the two previous albums Rubber Soul and Revolver. Sgt Pepper was a statement: the musical horizon was limitless.

It took five months to record, during which time critics were saying the band had had its day, and an enormous mount of money for the time. All manner of instrument played side by side, brass, string, electric, acoustic. George Harrison brought along the sitar. It was surreal, vaudevillian, plaintive, philosophical, optimistic and realist. Sir George said of Lennon’s intro phrase to Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds that ‘‘if Beethoven was around, he’d say, ‘I’d like one of those.’’’

And it concluded with a masterpiece, which was banned by the BBC. Perfect. The offending line was ‘‘I’d love to turn you on’’. Heaven forbid, BBC.

The album also had in With a Little Help from My Friends an instant standard, made all the more memorable with Ringo Starr’s deadpan singing and it had a drug controversy in Lennon’s Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds. Now what could the title possibly be conflated to mean? Yes, that’s it, his son Julian’s drawing from school. No matter. Perhaps Julian should have said it was Xavier up in the air.

This being the 60s, however, there were major fault lines between the generations. The Beatles weren’t anarchists, communists or fascists. Their agenda was not to bring down society (though you would think otherwise from the reaction they evoked in others). For instance, in the Rolling Stone History of Rock and Roll, Geoffrey Stokes quotes one Joseph Crow writing in the rightwing John Birch Society magazine: ‘‘I have no idea whether The Beatles know what they are doing or whether they are being used by some enormously sophisticated people, but it really doesn’t make any difference. It’s results that count, and The Beatles are the leading pied pipers creating promiscuity, an epidemic of drugs, youth class-consciousness and an atmosphere for social revolution.’’

That’s quite a load on the shoulders of four young men. That it was nonsense is obvious, but reactions such as those of Crow speak to the influence the band had in 1967. They were, after all, according to Lennon, bigger than Jesus. The non-comprehending heard not joy from music but fear through noise. Time has shown which to be true.

The Beatles only had another three years left in them. By today’s standards, they weren’t around for all that long — just seven years. (Some groups take that long to record one album.) In June 1967, the four lads were atop Everest. Sgt Pepper was the flag they left at the summit. Musicians and composers have been saluting it ever since.

The northern summer of 1967 may have been blessed with the release of Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band but, in all the overtures of love that have surrounded it, a voice should be raised for an equalling stunning achievement. Are You Experienced?, the debut album by Jimi Hendrix.

The guitarist had been plucked from a club in New York by Chas Chandler and transported to London where, within the space of an electric heartbeat, word had spread among the cognescenti [sic] of the British music scene of a guitarist of jaw-dropping virtuosity and inventiveness. He was a one-man revolution.

Hendrix may have paid his dues on the rhythm and blues circuit in the United States, but on arrival in England, it was though he had landed from Mars. Eric Clapton, who just happened to be ‘‘God’’ at the time to fans, Jeff Beck and Pete Townshend all made it their business to see him play. He was 24.

Are You Experienced? was released a month before Sgt Pepper in Britain, but not until August in the US. It was an album of startling innovation both in its playing and in its songwriting. Forget the stage tricks of playing his teeth or playing behind his back, which other blues guitarists, such as Buddy Guy, had been doing for years.

Hendrix took six strings on a Fender Stratocaster, fed them through an amp stack at ear-shredding volume, and set off aural detonations that are still felt in rock music. There were no boundaries.

Before the end of the year, he had released his second album, Axis: Bold as Love, as accomplished a feat as the first, and in 1968 came Electric Ladyland, his final studio album. Two years later, he was dead, aged 27.

His apocalyptic version of the American national anthem is a majestic piece of protest music. At the height of the Vietnam War, his guitar became the falling bombs, the explosions, the suffering and anger.

His was a singular talent: in the sounds he created he expanded the horizons of what was possible. His shadow falls still over every kid with an electric guitar, an amp and an attitude.